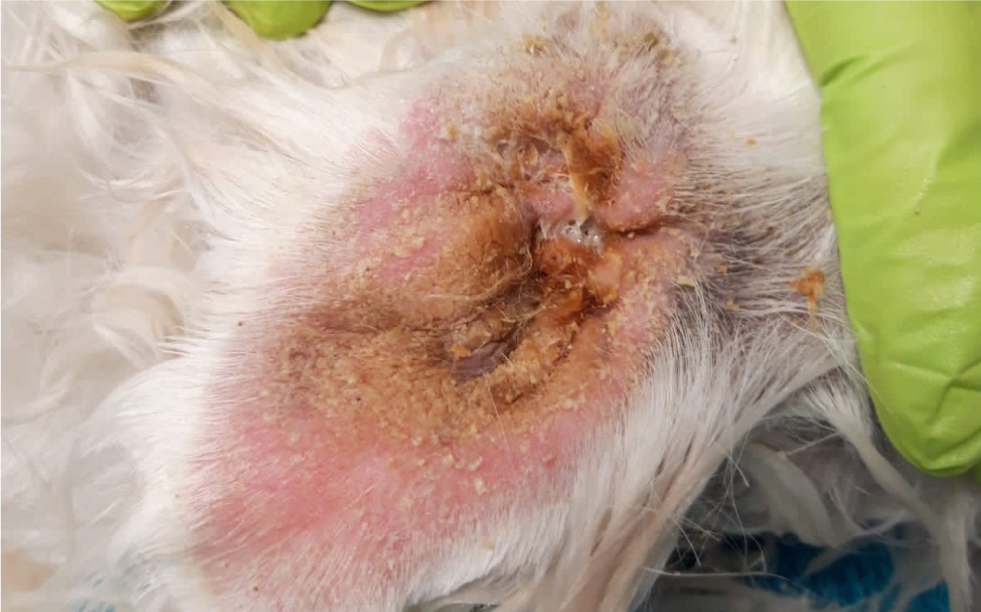

The incidence of otitis externa can be as high as 10% of the canine population (Hill et al, 2006). Cats (Figure 1) are much less commonly affected. Ear disease can be either unilateral or bilateral. Otitis (Figure 2) can be very painful for the patient and frustrating for owners and vets alike. In comparison to pruritus, otitis is just a clinical sign, not a final diagnosis.

Otitis is a multifactorial disease and it is important to identify and address all the different factors involved. To facilitate identification of these factors, the PSPP system (which stands for primary, secondary, predisposing and perpetuating factors) has been developed by August (1988) and should be followed in any patient with ear disease.

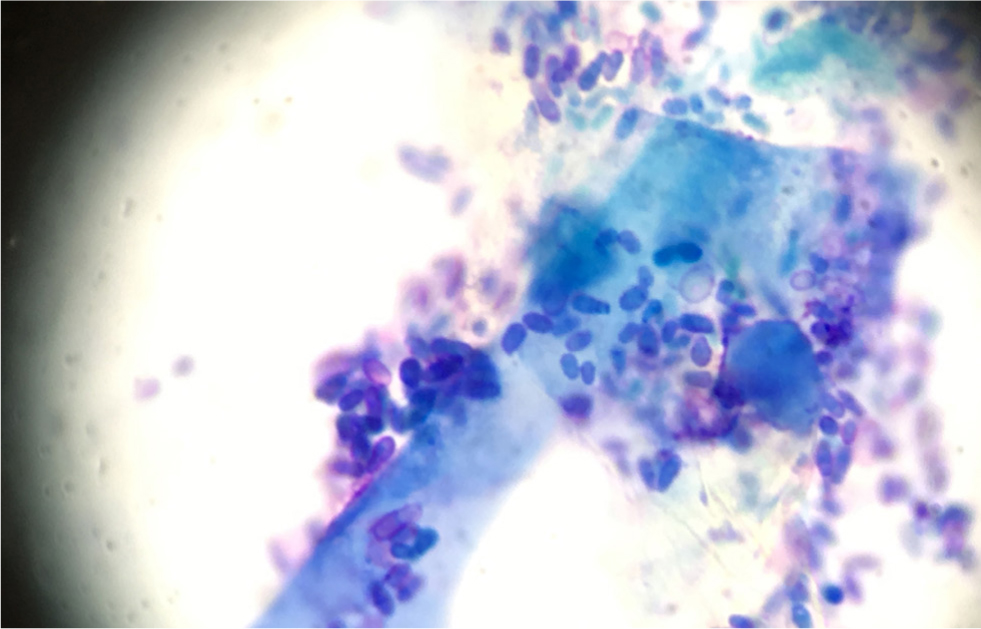

In addition to the primary disease, which drives the inflammation, secondary microbial overgrowth is a big factor in the aetiology of otitis externa. However, this is just in response to the primary disease initiating changes in the ear canal that make it favourable for microbial growth, such as an increase in temperature or humidity. The most common bacterial species found in cases of otitis are Staphylococcus spp. Other bacteria commonly implicated are Pseudomonas spp., Proteus spp., Enterococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., and Corynebacterium spp. Yeast (Figure 3), such as Malassezia spp. are also commonly associated with cases of otitis.

Ear disease can be associated with significant pain, which severely impairs quality of life. In addition, every episode of otitis leads to changes like ceruminous gland hyperplasia, stenosis, impaired self-cleaning mechanisms and potential breach of the tympanic membrane, predisposing the patient to further episodes of otitis. The process can eventually be self-perpetuating and in severe cases, repeated episodes of otitis can even lead to so called ‘end stage ears’, where changes such as calicification or even ossification make medical reversal of the disease almost impossible.

In these cases, the need for surgery arises. The most useful procedure is a total ear canal ablation with bulla osteotomy, a salvage procedure, with removal of the affected structured and subsequent loss of hearing for the dog. Therefore, early intervention is important to avoid this cycle of otitis, pain and impaired quality of life.

Normal ear canal

The normal ear canal (Figure 4a) has an L shape, is lined with epithelium and has ceruminal glands which make cerumen, containing many immunologically active substances. The canal ends in the tympanic membrane which separates the ear canal from the tympanic bulla, an air-filled structure.

There is a self-cleaning mechanism at work in the ear canal, which transports cerumen, small foreign bodies and keratinocytes out of the canal by means of turnover and growth of the cells of the lining of the ear canal towards the external auditory meatus. A self-cleaning mechanism with growth radially outward from the tympanic membrane has also been reported in dogs (Tabacca et al, 2011).

An increase of humidity, temperature, cerumen production, the microbial population and an influx of inflammatory cells can all disrupt the normal self-cleaning mechanism, leading to clinical signs of otitis externa (Figure 4b)

Clinical signs of otitis

Otitis can present as an acute episode, or be chronic (persistent or relapsing). Chronic inflammation leads to stenosis as a result of swelling, glandular hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis and glandular dilation (Huang et al, 2009). These changes in turn lead to an increase in humidity, pH and cerumen production, encouraging a new episode of otitis to occur. Microbial overgrowth occurs easily under these circumstances but some bacteria are able to produce a biofilm, rendering them less susceptible to antimicrobial therapy. The most commonly isolated bacteria are Staphylococcus spp. (Malayeri et al, 2010). The fungal mycobiota in unaffected dogs contains species of numerous different phyla and is dominated by yeast of the genus Malassezia in affected dogs (Korbelik et al, 2018).

Box 1.Primary factors and examples in patients with otitisEctoparasites:

- Otodectes

- Demodex

- Neotrombicula autumnalis

- Sarcoptes

- Ticks

Foreign bodies:

- Grass awns

- Sand

Allergic skin disease:

- Food-induced

- Environmentally-induced atopic dermatitis

Autoimmune and immune-mediated diseases:

- Pemphigus foliaceous

- Discoid lupus erythematosus

- Juvenile cellulitis

Cornification defects:

- Sebaceous adenitis

- Vitamin A-responsive dermatosis

Endocrine disease:

- Hypothyroidism

- Hyperadrenocorticism

Otitis is a very common occurrence (Hill et al, 2006) and thus a very common reason for presentation to small animal first opinion and referral practices. Clinical signs vary, and can include head shaking, otic discharge, malodour, pain, inflammation, hearing loss, head tilt and otic pruritus.

Primary, secondary, predisposing and perpetuating factors

Otitis is a multifactorial disease. The underlying factors consist of predisposing, primary and perpetuating factors, as well as secondary causes. If they are not all identified and addressed properly, it may be possible to resolve the acute infection. However, it is very likely that the patient will relapse, often worse than before (for example with multiresistant bacteria, such as multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas otitis or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in the ear canal).

Predisposing factors

These are defined as factors existing before the onset of the disease that contribute to the development of the disease, but do not solely cause clinical disease. Examples are the anatomical structure of the ear (for example a Shar-pei with congenitally stenotic ear canals), excessive hair growth in the ear canal (for example in Poodles), regular swimming resulting in increased humidity (swimmers' ear) or pendulous pinnae (Figure 5) restricting air flow to the ear canal (such as in Cocker Spaniels).

Primary factors

A number of factors are known to be potential primary factors in ear disease (Box 1). The most common one is allergic skin disease. In some cases the expression of the allergy is restricted to the ear alone with no other clinical signs (such as pruritus) present. Other primary factors are conditions such as a cornification defect, endocrine disease or a foreign body that can cause otitis in canine or feline patients.

Pepetuating factors

Factors that develop as a result of the otitis, and subsequently precipitate the occurrence of another episode of ear disease, are known as perpetuating factors (Box 2). Among those factors are conditions such as ceruminous gland hyperplasia, stenosis of the ear canal, scarring hyperplasia of the ear canal, calcification or even ossification of the cartilage.

Secondary factors

The skin, including the lining of the ear canal, is not sterile as it is usually inhabited by a large number of different microorganisms, forming the cutaneous or otic microbiome. Microorganisms such as cocci, rods and yeast constitute the secondary factors in the disease process; they multiply and add to the inflammatory process, when the conditions are right for them. This usually goes hand in hand with a loss of diversity in the microbiome and/or mycobiome.

In acute otitis, there is usually overgrowth of one or more of the resident or transient organisms. Increased numbers of microorganisms push the patient over the comfort threshold and lead to clearly visible signs of otitis. The most common microorganisms involved in cases of otitis are Malassezia spp. (Saridomichelakis et al, 2007) and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, Streptococci, Pseudomonas (Saridomichelakis et al, 2007), coliforms, Klebsiella, Proteus and E. coli can also be found relatively frequently.

Box 2.Predisposing and perpetuating factors in patients with otitisPredisposing factors:

- Increased ambient temperature

- Increase ambient humidity

- Abnormal conformation:

- Pendulous pinnae

- Stenosed ear canal

- Brachycephalic ear

Perpetuating factors:

- Overzealous cleaning

- Harsh cleaning products

- Contact reaction to topical medication

- Stenosis

- Fibrosis or calcification of the otic cartilages

- Cholesteatoma

- Otitis media

- Glandular hyperplasia (ceruminous glands)

Korbelik et al (2018) reported a dominance of Malassezia spp. in affected ears and a decreased observed richness, estimated richness and inverse Simpson's diversity index compared to controls, resulting in a less diverse mycobiome in ears with otitis. As Staphylococci usually have a known pattern of antibiotic sensitivity, and rods are less predictable in their antibiotic resistance pattern, it is important to identify which type of organism is involved in the infection. This will lead to a major differences in the treatment, prognosis and choice of further tests required. The most important test in the decision-making process for cases of otitis is therefore cytology.

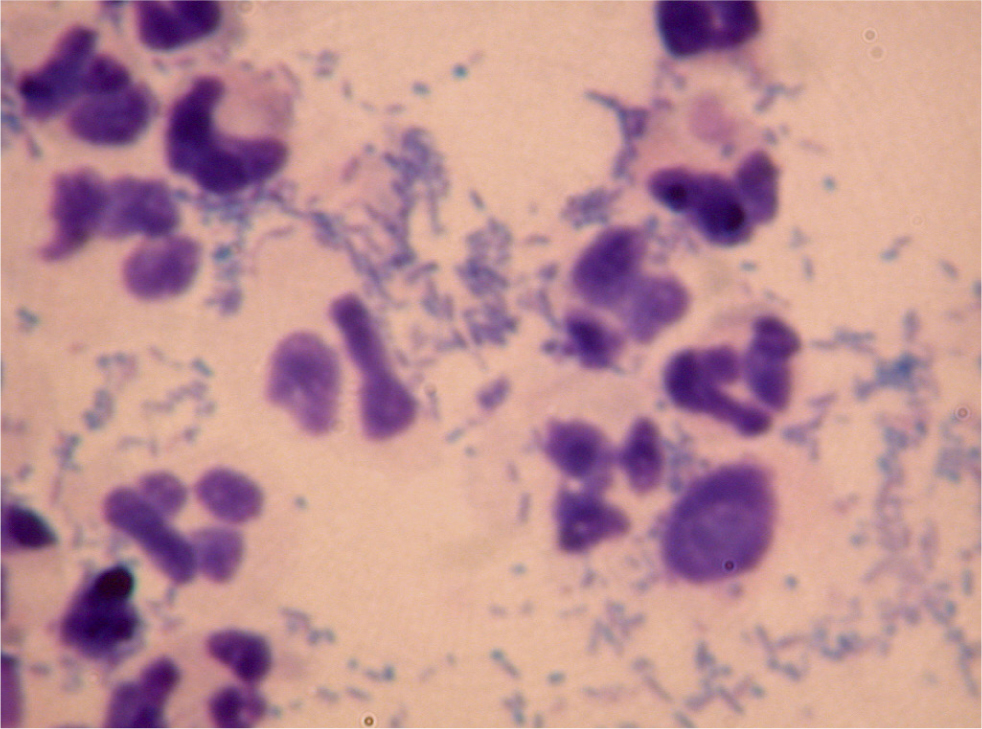

Cytology

Cytology is relatively quick, easy and cheap to perform in house. The purchase of a good quality microscope is vital for good results. Cytology gives an almost instant update of the status quo in each ear. With slight modifications, it can usually be performed even in the most fractious and aggressive animals. In amenable patients, a cotton bud is gently introduced into the ear canal to obtain a sample of the otic discharge. This is then carefully rolled out onto a microscopic glass slide and prepared for microscopic examination. In order to save slides and time, it is possible to use the same slide for samples from both ears by using the side right next to the frosted end for the right ear and the opposite end for the left ear (or vice versa). Romanovsky type staining sets are most commonly used in practice, although type of stain cannot distinguish between Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms. However, the shape of the bacteria is very suggestive of this variable (with the exception of Corynebacterium, which is rod shaped yet a Gram-positive organism). Various methods have been described and to some degree, they reflect personal preference. Most important details to note are the type and number of cells (keratinocytes, neutrophils etc) and microorganisms. Ginel et al (2002) considered mean bacterial counts per high-power dry field of ≥25 and mean Malassezia counts per high-power dry field of ≥5 to be abnormal in the external ear canals of dogs.

When cytology shows rod shaped organisms (Figure 6), culture and sensitivity testing is indicated in order to make the most suitable antibiotic choice, as well as to be able to give the client a more precise prognosis. The presence of rod-shaped bacteria in conjunction with severe clinical findings will also usually make more aggressive therapy necessary.

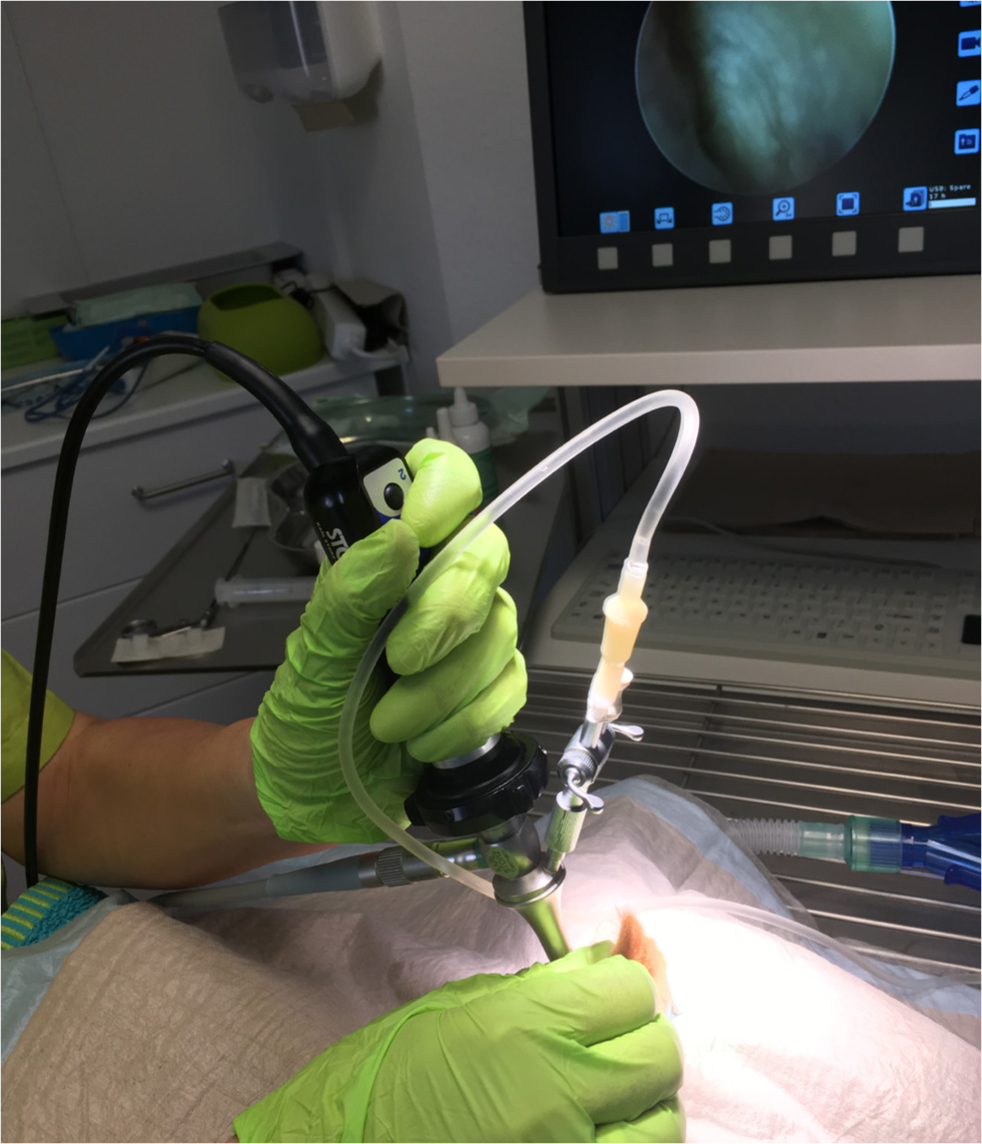

Otoscopy

Otoscopy is another important part in the examination of patients with otitis and without otoscopy, the deeper structures of the ear canal cannot be assessed. However, when the ear is very painful, this may need to be delayed by a few days while anti-inflammatory therapy is initiated. Otic stenosis caused by the inflammation of acute otitis can also be a prohibitive factor. A short course of glucocorticoids will help to control the inflammation and ‘open’ up the ear canal. This will increase the cooperation of the patient and help with the visualisation of the tympanic membrane. Medical and surgical otoscopes are available, as are video-otoscopes (Figure 8) and digital otoscopes, which can be used to document the changes in the ear canal. This can also be an important tool for client education.

Before performing otoscopy, it is important to warm up the ear cone to ensure best possible comfort during the procedure. Gently pulling up pinnae to stretch the ear canal during the examination helps reach the vertical canal as comfortably as possible for the patient. Good patient restraint is also important to avoid causing damage to the lining of the ear canal during the procedure. The normal ear canal is smooth, can contain a small amount of ear wax and some hair growth (with extensive breed variation). The normal tympanic membrane is smooth, glistening and translucent in appearance. In dogs that have become head-shy as a result of painful ears, aggressive animals and those in severe pain with stenotic ear canals, this type of examination may not be possible and may have to be performed after a course of glucocorticoids and in some cases, even under sedation or general anaesthesia.

Imaging

In patients with very chronic otitis, potentially with neurological signs and with suspected middle ear disease and/or inner ear disease, advanced imaging techniques may be indicated. Radiography is not a very sensitive modality, particularly for mild changes. Computed tomography provides excellent images of bony changes, while magnetic resonance imaging is better for assessing soft tissue disease. Table 1 shows the advantages and disadvantages of different techniques.

Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages of different imaging modalities to examine ear disease

| Modality | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Radiography |

|

|

| Ultrasound |

|

|

| Computed tomography |

|

|

| Magnetic resonance imaging |

|

|

Ear cleaning

It is important to remove the debris from the ear canal, as the microorganisms can hide in the material and make antimicrobial therapy ineffective. Some antibiotics are specifically inactivated by purulent material (such as polymyxin B). In addition, ear cleaners act in a similar way to shampoos on the skin; they can remove allergens, microorganisms, inflammatory cells and their by-products, working as an anti-septic and cerumenolytic. Ear cleaning actively helps to restore the natural self-cleaning mechanism with epithelial migration, which in diseased ears is overwhelmed by the amount of debris.

It is not possible to examine the deeper portions of the ear canal without removing the debris. Severely painful ears, for example in cases of Pseudomonas otitis, require in-practice cleaning, ideally with a video-otoscope, under general anaesthetic with very good analgesia, followed by at home top up flushes. Cleaning is usually combined with ear drops containing antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agents. Follow-up appointments are vital to ensure that therapy is successful.

Therapy

The goals of therapy are to clear the microbial overgrowth, remove debris, discharge and malodour, reverse the pathological changes to the ear structures, identify and treat the factors involved in the ear disease according to the PSPP system, and resolve the pain and pruritus associated with the otitis.

Topical therapy

Microbiology results will show the appropriate antibiotic sensitivity pattern against each organism. These days, antibiograms will include minimum inhibitory concentrations in order to determine the most effective antibiotic that will usually result in effective treatment. However, the break points used to determine minimum inhibitory concentrations are based on systemic antibiotic use. If used in an adequate quantity, topical medication can achieve much higher concentrations of active ingredients than systemic therapy can safely (Koch et al, 2012). In the interest of antibiotic stewardship, it is far preferable to expose only a small proportion of the patients' microbiome to an antibiotic agent. This form of therapy should therefore be used whenever possible.

Systemic therapy

Some select cases of otitis require systemic therapy. The most common clinical situation warranting this is animals presenting with severe pain and stenotic ear canals. These animals benefit from systemic glucocorticoids to provide analgesia and reduce the swelling, as well as having an otoprotective effect. For cases of ear mite infestation, systemic preparations such as selamectin or moxidectin spot on are useful. Some cases of otitis media can benefit from systemic antimicrobial therapy, but topical therapy can reach far higher concentrations and should always be tried first in amenable cases of otitis externa.

Ototoxocity

Ototoxicity is possible whenever any substances reach the middle and/or inner ear. In the absence of the tympanic membrane, ear cleaners, ear drops, inflammatory cells and their by-products, microorganisms and any or their secretions, or flushing solutions can enter the middle ear and potentially cause damage. However, in a clinical situation, ototoxicity is relatively uncommon. It is still worth warning the owner of this risk, particularly if in-practice cleaning is carried out and if the integrity of the tympanic membrane is unknown.

Clinicians need to be aware of substances that are more likely to cause problems and those that are deemed safe in the middle ear. Fluoroquinolones, squalene, TrisEDTA, clotrimazole, micronazole, dexamethasone are deemed to be relatively safe in the middle ear but there is no ear preparation that is licenced to be used in cases where the tympanic membrane is compromised, and there is only anecdotal evidence to support this. Ticarcillin, polymyxin B, neomycin, tobramycin and amikacin are potentially ototoxic in dogs with a ruptured tympanic membrane. The risk associated with gentamycin may be overstated (Patterson, 2008).

Follow up and client education

Regular follow ups are vital for the successful long-term management of cases of otitis. After an episode of acute otitis treated with course of eardrops and regular cleaning, it is important to monitor progress with regular clinical examinations and follow up cytologies. In addition, the underlying primary disease needs to be investigated and managed. Further tests such as advanced imaging or allergy testing may be indicated. A long-term strategy needs to be put in place to address the primary disease in order to avoid relapses. This often includes the regular use of ear cleaners, as epithelial migration may take a while to recover. Client education is vital to foster compliance in these long term, chronic cases.

Surgery

‘End stage’ ears may have to undergo a total ear canal ablation to remove the severely diseased tissue. This is a rescue procedure and should only be performed if medical management has not been able to achieve a satisfactory improvement and the patient is in pain. A lateral wall resection can be helpful in cases of congenital stenotic ears (for example, in some Shar-peis).

Conclusions

Otitis is a multifactorial disease and needs to be addressed in a multimodal fashion. An integrated approach dealing with the acute otitis and addressing the secondary factors, as well as investigating the primary disease and treating the perpetuating factors, is essential for all cases of otitis. A long-term strategy is needed and progress needs to be reviewed during regular follow-up appointments.

Many cases of otitis benefit from referral, particularly cases of Pseudomonas otitis, as a deep flush under general anaesthetic with a video-otoscope is extremely useful for resolving otitis. A thorough investigation of the primary disease is also needed to formulate a long-term plan and increase quality of life in affected dogs.

KEY POINTS

- Otitis externa is a multifactorial disease.

- Remember to identify primary, secondary, predisposing and perpetuating factors.

- Cytology is vital to identify the organisms involved and monitor progress.

- Scheduling regular follow up appointments is vital for successful management.

- Choose the cleaner based on the type of otic discharge.

- Choose the drops based on the organisms present and the status of the tympanic membrane.