Birds have a unique respiratory anatomy, with some clinically important features. The upper respiratory tract comprises the nasal passages that connect to a large air-filled infraorbital sinus. The infraorbital sinus is particularly well developed in psittacines and extends rostroventral to the eye (König et al, 2016). Air flows from the nasal cavity through the choana, a slit in the roof of the mouth, and through the glottis, which is positioned at the base of the tongue. The trachea comprises complete rings of cartilage. The syrinx is used for vocalisation and is positioned just cranial to the tracheal bifurcation. The lungs are composed of semi-rigid parabronchi, which have a unidirectional flow of air, allowing a very efficient cross current for gas exchange (O’Malley, 2005). The air sacs are poorly vascularised and act as bellows to push air over the lungs during both inspiration and expiration. They are not involved in gas exchange. Birds lack a diaphragm and both inspiration and expiration are active processes involving outward movement of the ribs and sternum. For this reason, it is important not to place too much pressure around the thorax during handling as ventilation can be significantly compromised (O’Malley, 2005).

History

The history may be mild and chronic, such as intermittent sneezing or wheezing, or cases may present in acute respiratory distress. Birds are prey species and will hide signs of illness until disease is advanced. Cases that present with a sudden onset of severe clinical signs will often have been masking more chronic disease for a prolonged period, without the owner’s knowledge (Korbel et al, 2016).

A thorough history should be taken with attention paid to any recent changes to the flock or to the environment in which the bird is kept. Many respiratory diseases are associated with poor management or inadequate nutrition, and owners should be questioned in detail regarding husbandry. Pet parrots are often fed a predominantly seed-based diet that encourages selective feeding and is deficient in vitamins A and D and calcium. Hypovitaminosis A leads to keratinisation of the mucous membranes lining the respiratory tract (Orosz, 2014), which can predispose to opportunistic infection. Exposure to inhaled irritants such as cigarette smoke, air freshener sprays and plug-ins and other aerosols can have an irritant effect on the respiratory tract and fumes from overheated Teflon pans can have fatal toxic effects.

A change of voice should alert the clinician to the possibility of tracheal inflammation or a lesion at the syrinx, a common site for aspergilloma formation (Martel, 2016).

Clinical examination

The bird should first be observed at a distance. Common signs of illness include fluffed feathers, closed eyes, inability to perch, increased respiratory effort with tail bobbing or open mouth breathing. Video 1 [video1.mov] shows a budgerigar with significantly increased respiratory rate and effort: note the upright posture and marked tail bob. A dyspnoeic bird, showing marked respiratory effort or open mouth breathing, should only be handled long enough to quickly transfer to a warm (28–30°C), oxygen enriched environment and allowed to stabilise (Orosz and Lichtenberger, 2011). The bird’s transport container can be covered and used as an oxygen chamber if necessary.

A more stable patient can be handled carefully for a full clinical examination. Weight loss or poor body condition should alert the clinician to the likelihood of a chronic disease process. Obese birds may show respiratory effort as a result of an enlarged liver (hepatic lipidosis) or intracoelomic fat deposits. Changes to feather colour or quality can be associated with nutritional deficiencies or metabolic disease (particularly hepatic disease).

The nares should be checked for the presence of rhinoliths. These are concretions of cellular debris and discharge that can partially or fully occlude the passage of air. They can become large and cause deformity of the nostril. Matting of the feathers around the nares or top of the head indicates nasal discharge. The choana should be observed for swelling or discharge. The normal anatomy of the hard palate surrounding the choanal slit consists of papillae which are often blunted in case of hypovitaminosis A (Bowles et al, 2007). Periocular swelling is a common feature of sinusitis and may be uni- or bilateral. Discharge accumulates in the sinus and may become inspissated.

The lungs should be auscultated over the dorsal body wall and the air sacs also auscultated. Coelomic palpation will determine if effusion, mass or an egg are present.

Stabilisation

In addition to placing the bird in a warm, oxygenated environment, initial critical care includes fluid therapy and nutritional support, administered once the bird is stabilised enough to tolerate handling (Divers, 2010). Sick birds are often anorexic and if so can be assumed to be at least 5–10% dehydrated. Nutritional support can be provided using a liquid critical care diet delivered via crop tube, at a volume of 1–3% bodyweight per feed two to three times daily. Suitable choices for psittacines include Harrison’s Recovery formula and Lafeber Emeraid critical care diet for omnivores. Fluids are generally given by the subcutaneous route (the precrural fold at the medial thigh is the most suitable site for administration) and the addition of hyaluronidase to the fluids may increase the speed of absorption (Tully, 2000) but is not essential. The volume given should not exceed 1% bodyweight per site. For more critical patients the intravenous or intraosseous routes can be used. The maintenance rate for most psittacine species is 100 ml/kg/day. Midazolam may be administered for anxiolysis at 0.1–0.5 mg/kg intramuscular or 2 mg/kg intranasal.

If a tracheal obstruction is suspected by an inhaled foreign body or an aspergillus abscess at the syrinx, then an air sac tube needs to be placed immediately (Orosz and Lichtenberger, 2011). The bird is anaesthetised and placed in right lateral recumbency (the left caudal thoracic air sac is larger than the right) and the entry site just caudal to the last rib and cranial to the thigh is aseptically prepared. The skin is incised, and curved mosquito forceps used to bluntly dissect through the body wall and into the air sac. The cannula is inserted and sutured into place (Figures 1–3). The bird can then be ventilated through the air sac tube while the obstruction is managed. The tube can be left in place for 5–7 days if necessary but should be closely monitored for mucus build up or foreign body obstruction, and animals with a tube in should avoid dusty/dirty environments.

Diagnostics

Once the patient is stabilised, further investigations should be performed to reach a specific diagnosis and allow appropriate further treatment. A blood sample can be taken from the right jugular vein, either conscious or under a brief gaseous anaesthetic. The cutaneous ulna vein and medial metatarsal vein are alternative collection sites. A volume of no more than 1% of bodyweight should be taken (1 ml/100g) and some authors suggest no more than 0.4–0.5 ml/100g bodyweight for a critical patient (Bowles et al, 2007). This should be submitted for haematology and biochemistry evaluation to a laboratory experienced in dealing with avian samples. For small samples, 0.5 ml heparin tubes are available and the heparinised blood can be used for haematology as well as biochemistry. Fresh air-dried blood smears should also be submitted.

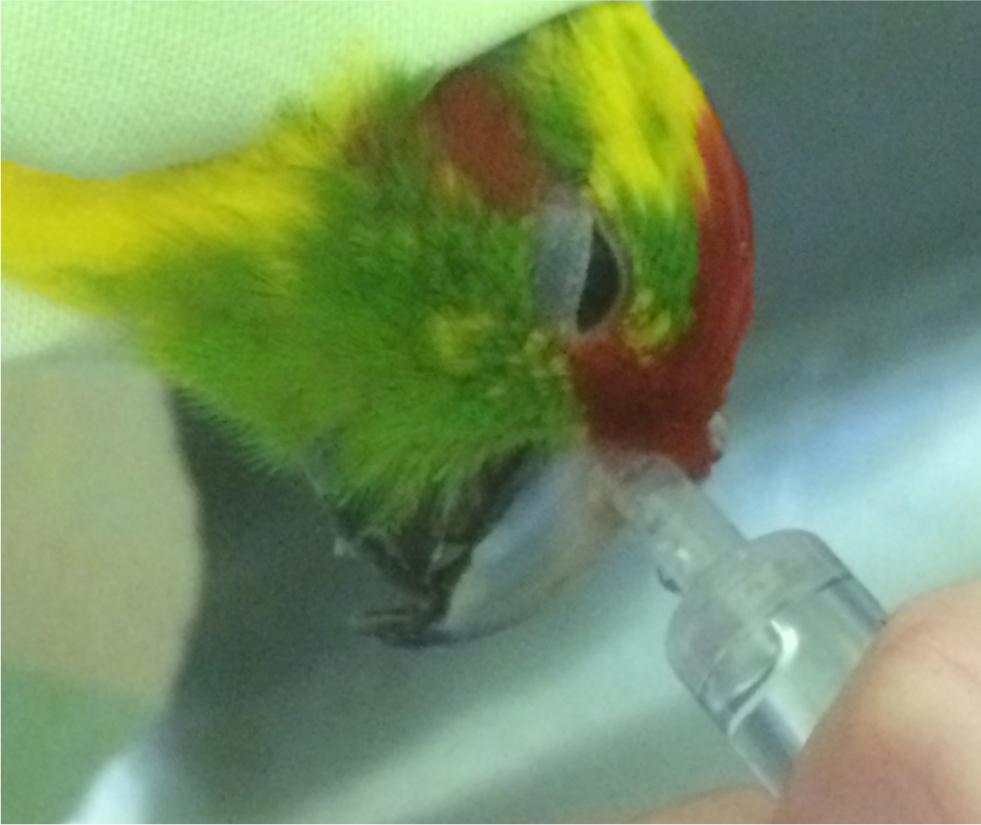

Samples for culture and cytology can be easily obtained from the upper respiratory tract. Swabs may be taken from the choana if discharge is present. A nasal flush can be performed for therapeutic and/or diagnostic purposes with a syringe held against the nares and 2–5 ml/kg saline flushed through with the bird’s head inverted (Bowles et al, 2007). The fluid is collected as it flushes out of the choana (Figure 4). Nasal flushing can be achieved easily in the conscious bird and can be repeated daily if needed.

In most cases, radiology will be required to further assess the respiratory tract. Ventrodorsal and lateral views should be obtained under sedation or anaesthesia, with the limbs extended away from the body to prevent superimposition. Changes to the structure of the lungs can be visualised, alongside abnormalities within the air sacs or enlarged organs compressing the air sacs. On the lateral view, thickened air sacs may be visualised as lines crossing the radiolucent air sac field.

Rigid endoscopy can be a very helpful technique, although it requires specialist equipment. Tracheal endoscopy can identify lesions at the level of the syrinx. Air sac endoscopy is used to visualise the lungs, air sacs and other coelomic organs and to obtain samples for culture, cytology or histopathology (Divers, 2010).

Common differential diagnoses and treatment

Respiratory distress may be caused by primary disease of the respiratory system or may be secondary to coelomic pathology causing compression of the air sacs. Non-respiratory causes of respiratory distress are summarised in Box 1.

Box 1.Non-respiratory causes of dyspnoea in avian patients

- Organomegaly

- Egg-binding

- Cardiac disease

- Ascites

- Obesity

- Goitre

- Coelomitis leading to adhesions

Rhinoliths should be carefully removed and submitted for bacterial and fungal culture and cytology. Care should be taken when removing very large rhinoliths as the underlying tissue bleeds easily (Figure 5) and general anaesthesia should be considered. Diet should be corrected as these lesions are often secondary to squamous metaplasia as a result of hypovitaminosis A. Regular flushing may be required and systemic treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to control pain and inflammation plus systemic and topical antibiotics and/or antifungals based on culture results may be needed.

If sinusitis is present, then aspiration or lavage of the infraorbital sinus is required to obtain samples for culture and cytology. A small gauge hypodermic needle is inserted into the preorbital diverticulum just dorsal to the jugal arch. Fluid can be aspirated or instilled and drained. Exudate may become inspissated, necessitating surgical debridement before flushing (Girling, 2005).

Bacterial infections are common in both the upper and lower respiratory tract. Common species include Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., Pseudomonas spp. and Klebsiella spp. Chlamydiosis is very common and causes both upper and lower respiratory tract disease and hepatitis. The causative agent is the intracellular bacterium Chlamydia psittaci and owners should be advised that the infection is zoonotic. A carrier status is possible, with disease causing clinical signs after a period of stress, which in some cases can be many months or years after the initial infection. Blood results typically show elevated levels of liver enzymes and a marked leucocytosis, of which monocytosis is often a feature. Radiographs show hepatosplenomegaly and air sacculitis. A polymerase chain reaction test and serology are available and should be performed in any suspicious case. A pooled 5-day faecal sample can be submitted for polymerase chain reaction to detect latent carriers, although false negative tests are common as the organism is intermittently shed. The treatment of choice is doxycycline, administered for a 45-day period (Tully, 2000) at 15–50 mg/kg orally every 24 hours.

Fungal infection with Aspergillus spp. is also common and usually occurs in birds with underlying disease such as malnutrition, hypovitaminosis A or immune system dysfunction, for example with circovirus infection or following treatment with corticosteroids. Fungal spores are ubiquitous in the environment and infection is opportunistic rather than via bird-to-bird transmission. Clinical signs are non-specific and include lethargy, exercise intolerance, weight loss and gastrointestinal signs. Respiratory signs may or may not be a feature and can include loss of voice or dyspnoea in the case of tracheal lesions and progressive respiratory signs in the case of lower respiratory tract disease. Blood results often show elevated total protein and marked leucocytosis comprising a heterophilia with left shift and monocytosis, however, immunosuppressed birds may show hypoproteinaemia and a white cell count within the normal range (Martel, 2016). Radiographs may demonstrate air sacculitis or if disease is advanced, granulomas within the air sacs (Figures 6and7). Typical lesions may be visualised in the trachea (usually at the syrinx), or within the air sacs, via rigid endoscopic examination. Prognosis varies depending on the extent of the infection and underlying health status but is often guarded. Treatment usually comprises a combination of debulking of lesions, topical treatment either directly onto lesions at endoscopy or via nebulisation, systemic antifungal drugs such as voriconazole, itraconazole or terbinafine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and addressing of underlying disease. Itraconazole should be avoided in Grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus) as they are reported to not tolerate this drug well (Tully, 2000).

Inhaled toxins can result in acute and severe dyspnoea. The most common of these is exposure to fumes from overheated Teflon pans (PTFE toxicity). Aerosol sprays, plug-in air fresheners and cigarette smoke are also irritants (Orosz and Lichtenberger, 2011). Treatment is symptomatic with oxygen and supportive care as described previously.

The air sacs are not well vascularised, and the systemic drugs may be poorly absorbed. Nebulisation is a low stress method for providing medications directly to the respiratory tract. If necessary, the bird can be nebulised in its own cage, with towels used as a covering to retain the vapour. The nebulisation unit should provide a particle size small enough to penetrate the lower respiratory tract: approximately 5 microns is recommended (Chitty, 2008). There are many protocols for antibiotic and antifungal medications to be delivered by nebulisation and an up to date exotics formulary should be consulted for specific protocols. The quaternary ammonium compound F10 antiseptic solution may also be used at a concentration rate of 1 ml F10 into 250 ml water (Stanford, 2001). Bronchodilators can be used in the nebuliser, which can aid in the treatment of respiratory distress alongside oxygenation and assist penetration of nebulised medications by opening the airways. An example is salbutamol, and this may be done before nebulisation with dilute F10 or similar.

Treatment must not only target the infectious process but also correction of the underlying risk factors such as poor nutrition and husbandry. Barrier nursing and a separate air space for hospitalised avian patients is required to prevent cross contamination in the case of infectious disease.

Conclusions

Respiratory disease is common in psittacine birds. With a logical approach, accurate diagnosis and successful treatment are possible in a general practice setting.

KEY POINTS

- Respiratory disease is a common presentation in psittacine species, and their unique anatomy and physiology mean they require a different approach to that of mammalian species with respiratory disease.

- Respiratory infections are commonly secondary to husbandry problems, such as seed-based diets that allow selective feeding leading to hypovitaminosis A, and inhaled irritants in the environment.

- Upper respiratory tract diseases include rhinitis and sinusitis. Rhinoliths may be a feature.

- Infectious lower respiratory tract disease includes Chlamydia psittaci infection and aspergillosis and can be diagnosed by a combination of haematology, biochemistry, radiography, rigid endoscopy and polymerase chain reaction.

- Treatment of respiratory disease includes systemic antimicrobials, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and inhaled medications administered via nebulisation.

- Correction of risk factors such as poor diet and husbandry practices must also be achieved for a successful outcome.