In this article the diagnostic approach to canine and feline dermatoses is discussed. Careful history taking, a thorough examination of the patient (both systemic and dermatological) allows a diagnostic plan to be constructed leading to a final diagnosis. The use of history and examination forms can aid this approach, leading to a repeatable process in the clinic.

Diagnostic approach

The approach to diagnosis is based upon completing the following steps:

- History

- Clinical examination

- Differential diagnosis list

- Diagnostic tests

- Final diagnosis.

History

It is essential to take a thorough history both of the animal's general health and the skin problem. Owners are always very focused on the main problem as they perceive it: to ignore this is to risk losing cooperation early in the diagnostic process, but it is all too easy to be swept along and forget to ask questions that may be important to the final diagnosis. Establishing a rapport with the owner is important as the diagnosis and management of a skin disorder can take place over some time and several visits. Owners may be anxious and may miss giving important information if they feel hurried.

The history always starts with the signalment; the second of this series of papers will discuss the diagnostic clues which can come from consideration of breed, age and gender.

A family history of skin disease can be useful, but should not be used to short-cut the diagnostic process.

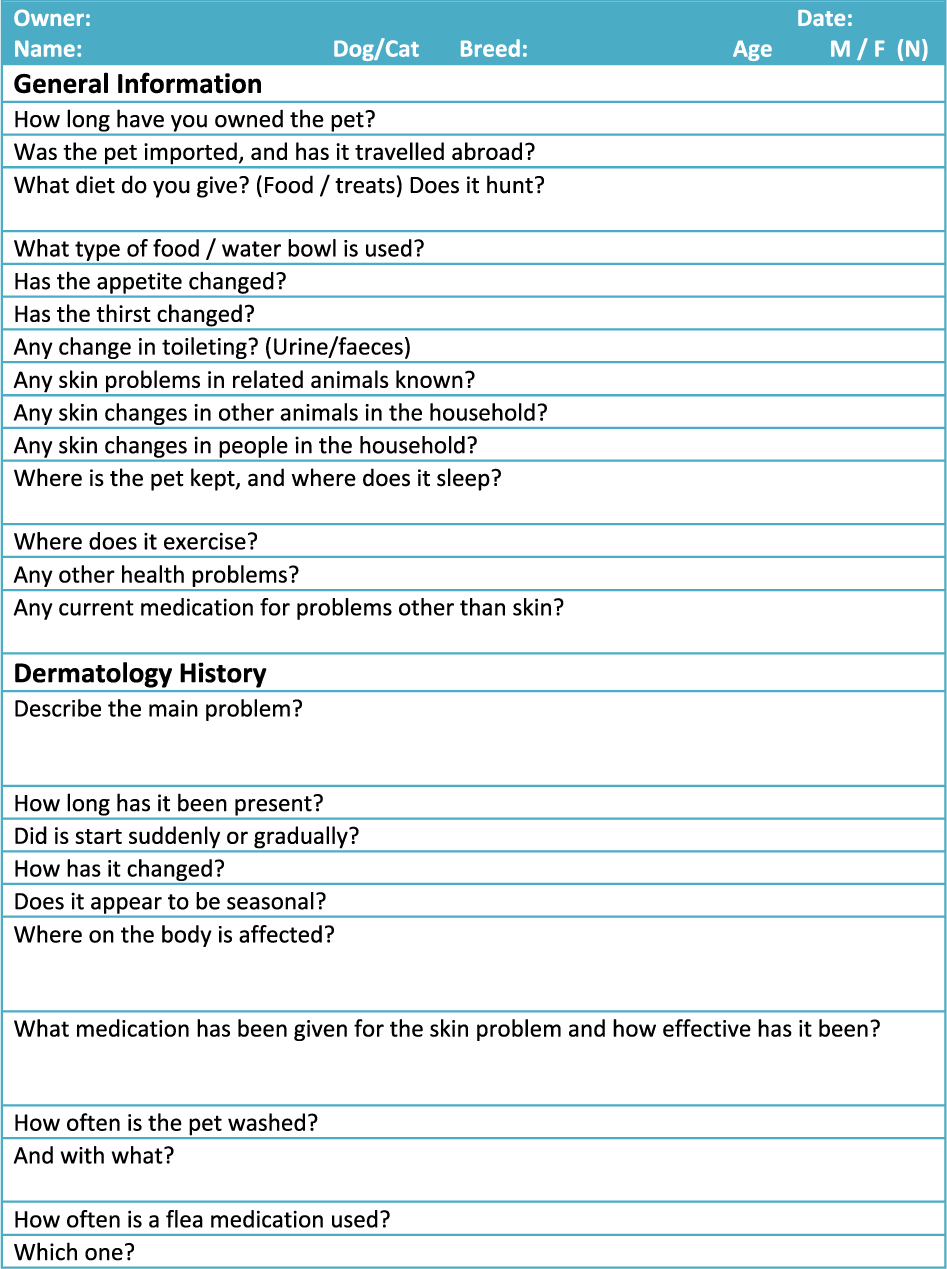

One way of ensuring a full history is to ask the owner to fill in a history form (Figure 1). This can be e-mailed to the owner before the appointment, but should be looked at with the owner present to clarify any points. It can also highlight areas of concern: for example, if an increase in thirst is indicated the owner may be asked to collect a urine sample from the pet before the appointment.

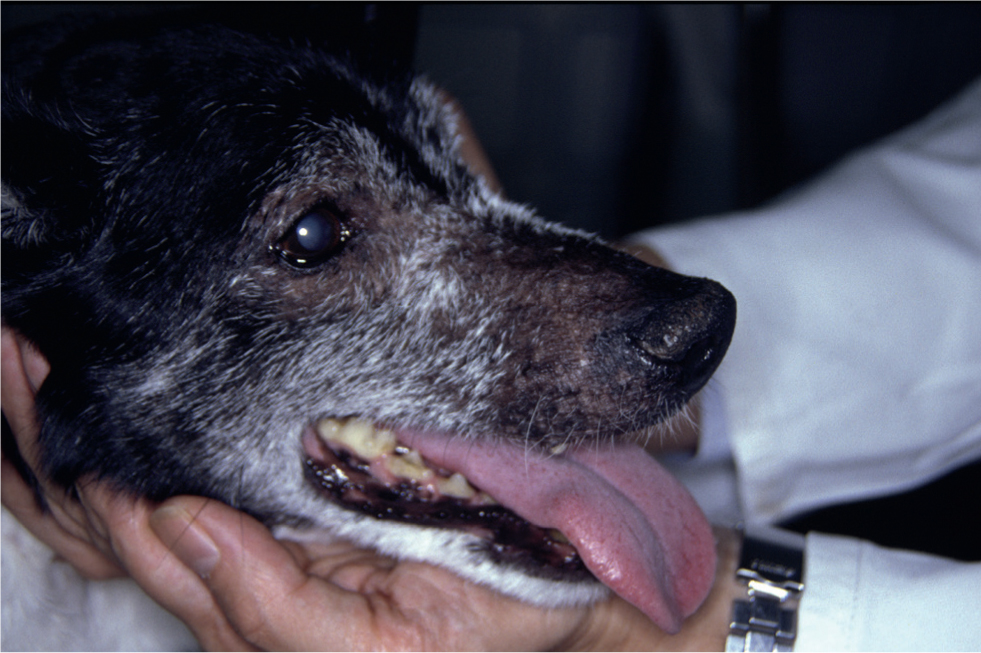

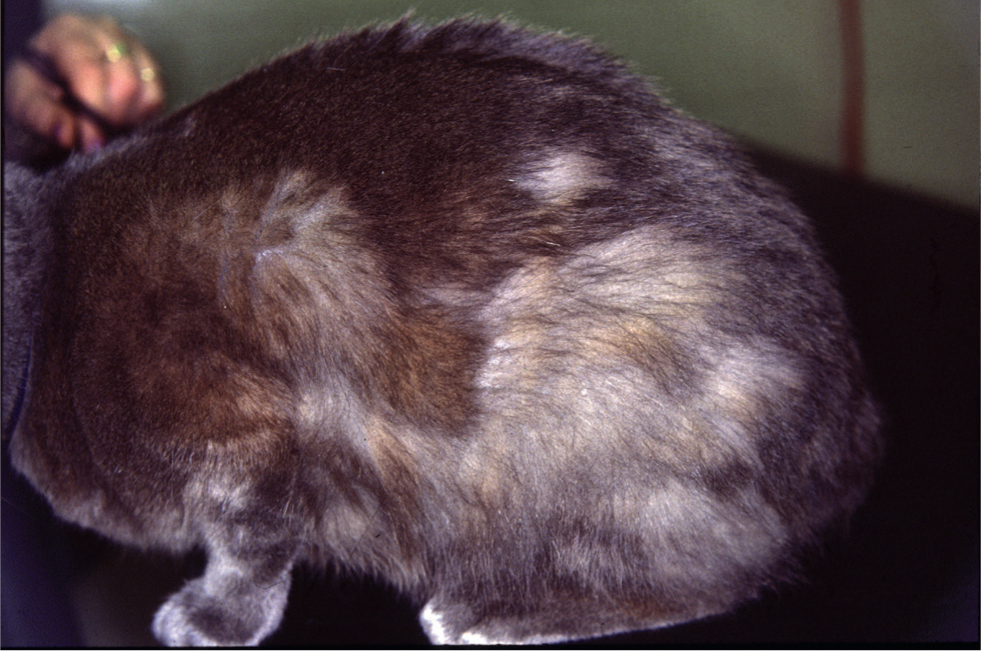

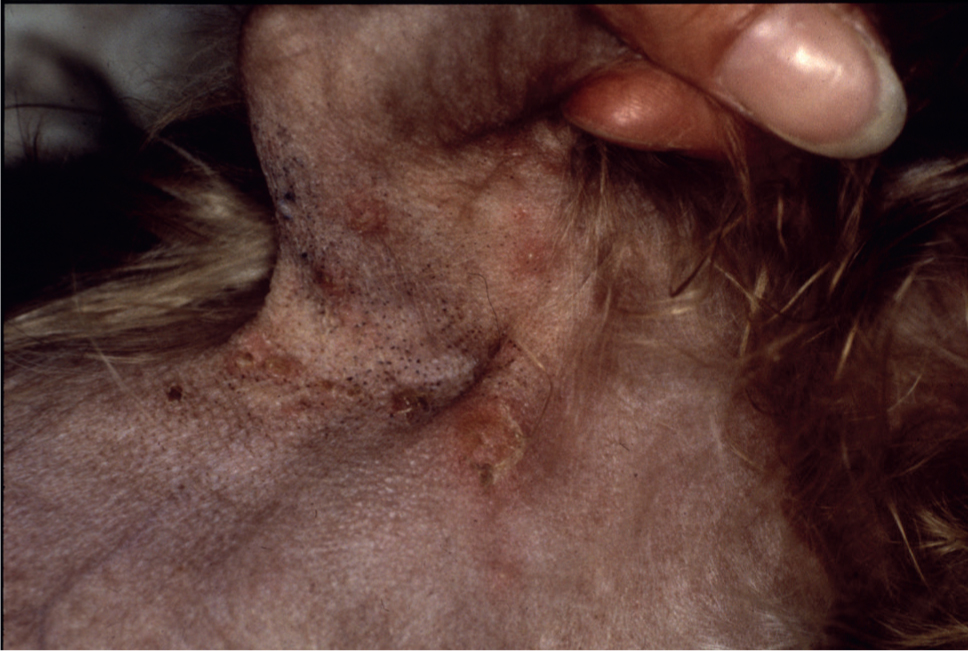

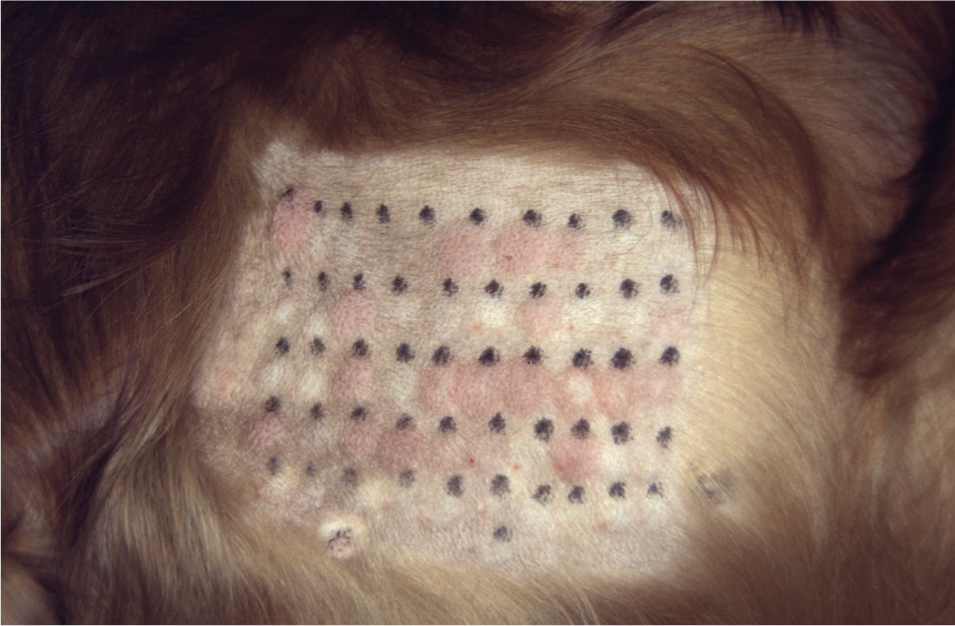

Discussion of where dogs exercise not only indicates what types of pollen contact is likely, but also whether there is contact with wildlife such as foxes (sarcoptic mange; Figure 2) or hedgehogs (fleas or Trichophyton erinacei dermatophytosis). Cats or dogs that hunt may be exposed to small mammals harbouring Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Microsporum persicolor dermatophytes (Bond et al, 1992) (Figure 3) or cowpox virus.

Taking a detailed dietary history can be time consuming and incomplete. It can be rewarding to ask the owner to complete a food diary for a week (encourage the owner to feed normally and not to avoid the foodstuffs they feel you would disapprove of) and it is often a good idea to get them to involve the whole family in this. The presence of children in the consulting room can often reveal a degree of dietary honesty which may not otherwise be seen!

The medication history is important, both in determining concurrent illnesses, and assessing the response to treatment. All medications may have a bearing on the current problem; those which have successfully removed a part of the disease presentation such as secondary infection, and those which may alter the appearance or progression of the disease such as glucocorticoids. It is useful to explain the limitations of some medications: their apparent failure may have resulted from unrealistic expectation rather than treatment failure, and they may be useful again in the future. Assessment of the level of ectoparasiticide treatment is important; the owners' understanding of regular treatment may be different to yours. Assessment of factors that may limit the efficacy of such treatments is also useful; topical treatments may be of limited use in the dog that swims regularly.

Owners may also have photographs documenting the progression of the disease: this can be useful in slowly progressing changes involving the coat density or pigmentation (Figure 4).

Examination

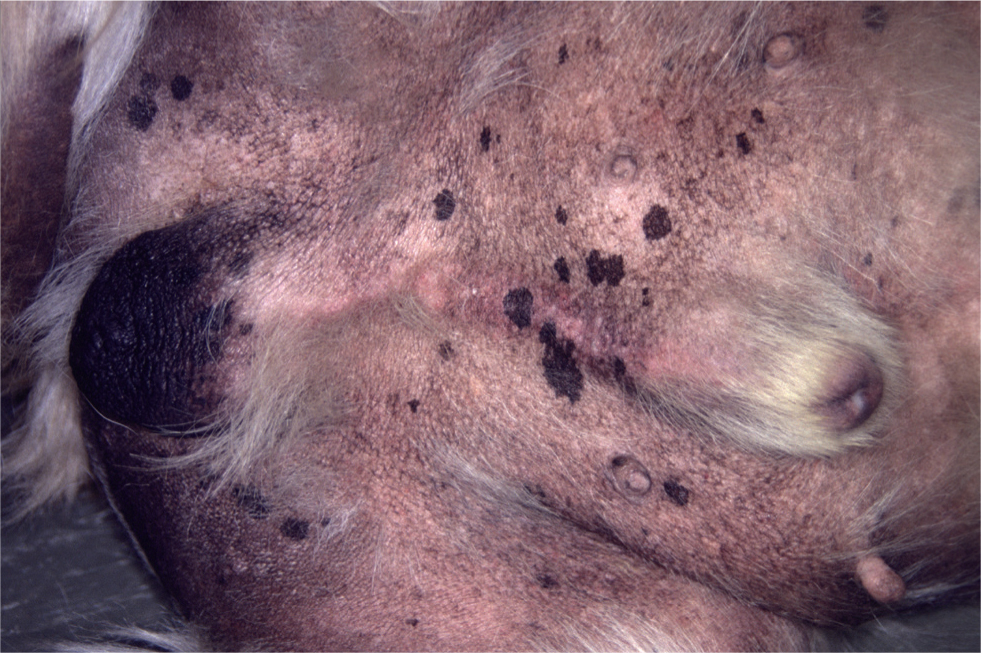

While again the owner may wish you to focus on the main area of problems, it is important to start with a thorough clinical examination of the dog. I am always surprised when I find an undiagnosed testicular tumour in a dog referred for a dermatology appointment (Figure 5). The presence of a concurrent systemic illness may affect the ability to use chemical restraint for further examination, and may make some treatment options inadvisable.

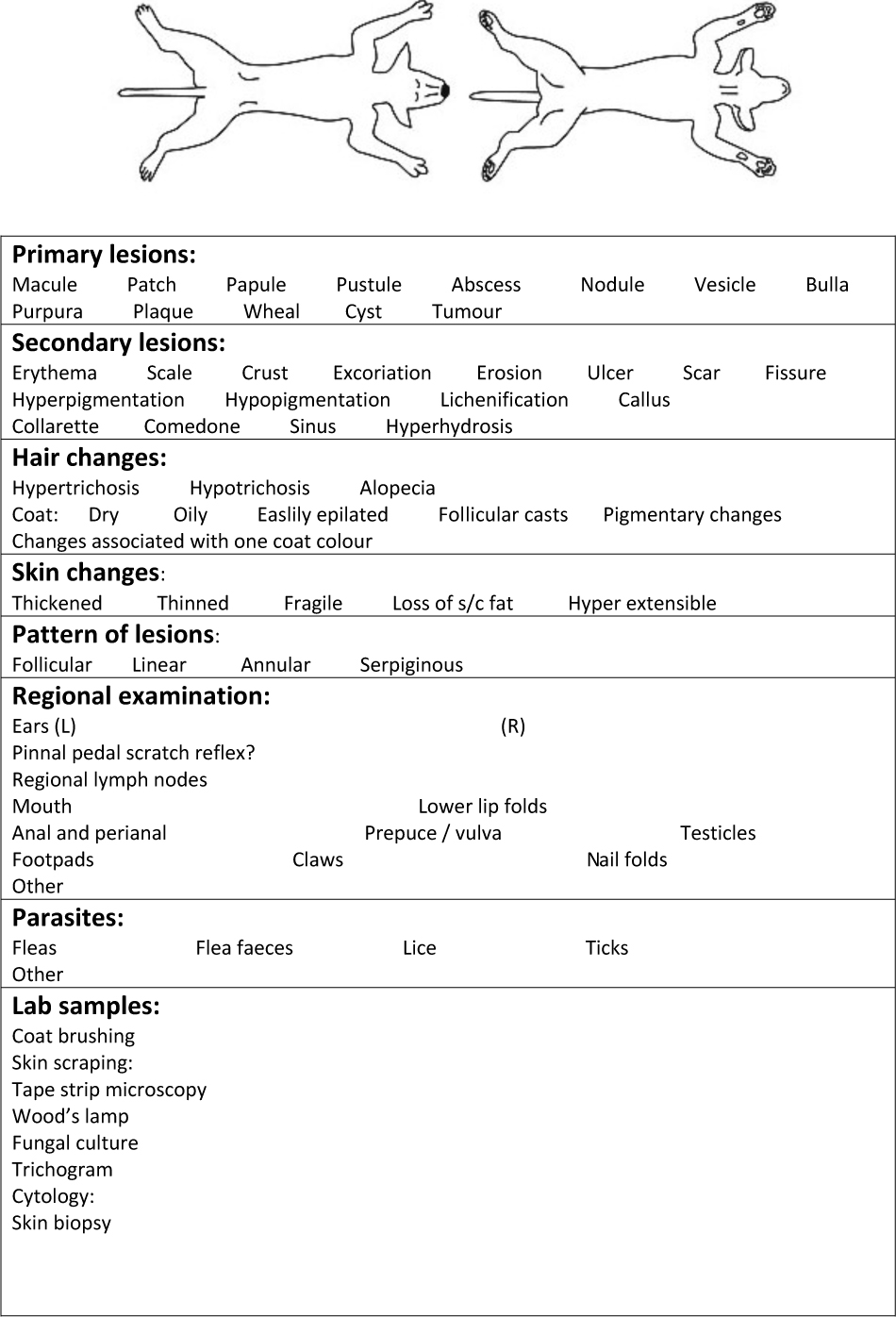

Examination of the skin should be thorough and systematic to avoid missing important areas. This is especially important for difficult to examine areas such as lip folds if the dog needs to be muzzled. The use of an illuminated hand lens can be useful. It can be helpful to have an examination sheet (Figure 6) to help with this approach.

Finding primary lesions can be very helpful, although the thin epidermis in dogs and cats, together with the effects of self trauma in the pruritic patient, can make these lesions quite transient. The presence of secondary lesions such as epidermal collarettes can indicate the need for a careful search for intact pustules (Figure 7).

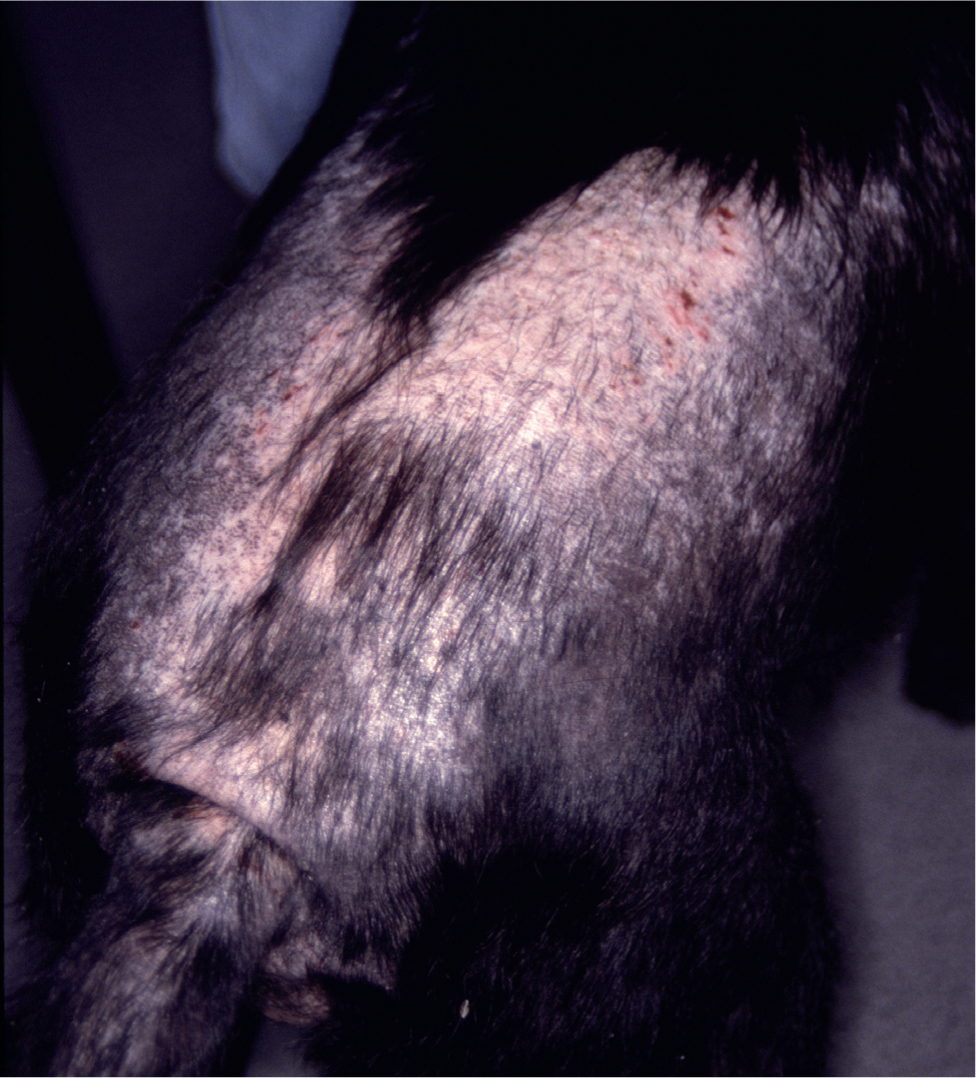

Examination of the pattern of pruritus can be useful: lesions limited to the dorsal lumbosacral region may indicate flea allergic dermatitis in the dog (Figure 8), and ventral pruritus involving the face and feet may indicate atopic dermatitis. The pattern of self trauma is of less value in the cat, where individual cats may have favourite places to groom excessively, whatever the cause of the pruritus. The pattern of pruritus can sometimes be influenced by secondary changes: bacterial or yeast overgrowth in skin folds (intertrigo) can be a stronger pattern than the underlying atopic dermatitis (Scarff, 2016).

Differential diagnosis list

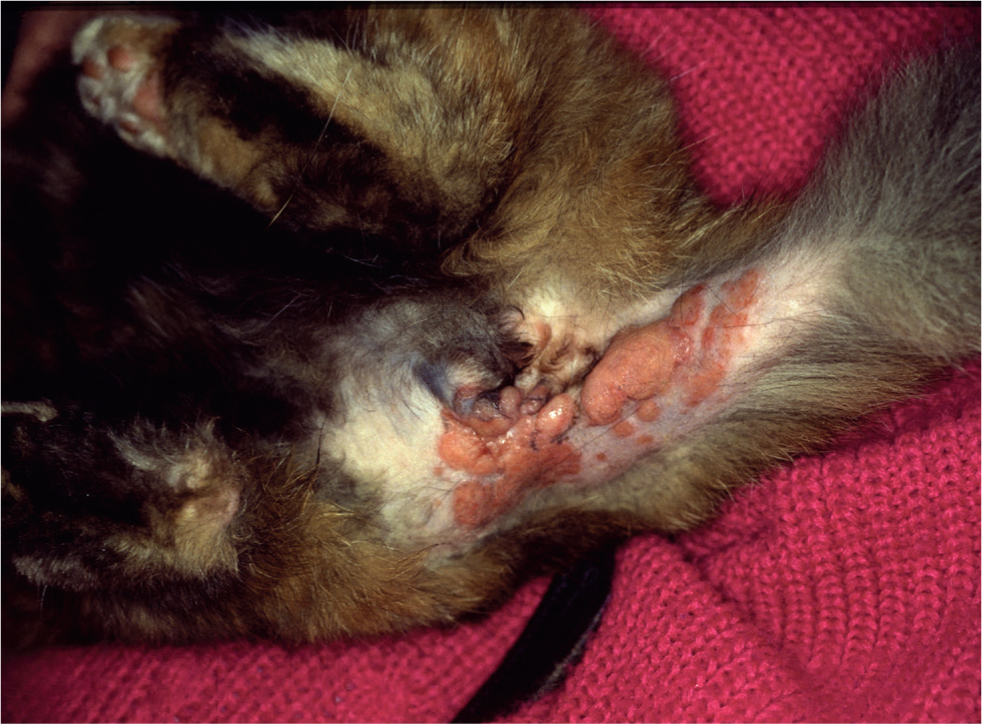

Following the history and clinical examination it is useful to create a list of possible differential diagnoses. While all options should be included, it is still important to remember that common problems are more likely — hair loss in the cat is far more likely to be caused by flea allergic dermatitis than alopecia mucinosa. However, although feline cowpox infection is also rare, treating it with glucocorticoids as an assumed case of eosinophilic plaque can have serious effects on the progression of the disease (Bennett et al, 1990) (Figures 9 and 10). If both diseases are on the list, a more measured approach is likely.

Following the construction of the list, diagnostic tests can be selected that will allow the list to be narrowed, and hopefully will allow a final diagnosis to be achieved.

Diagnostic tests

Diagnostic tests that are useful in the diagnosis of dermatology cases are listed in Table 1. Tests should be targeted at confirming or ruling out problems in the differential diagnosis list, and consideration should be given both to the cost/benefit ratio and also to the information that they provide and the use that information may contribute. An intradermal skin test (Figure 11), for example, may provide a lot of useful information in an atopic dog or cat, but is not necessary for the diagnosis of this condition (Favrot et al, 2010), and unless desensitisation or allergen avoidance is to be considered, it is not justified.

Table 1. Diagnostic tests in dermatology

| Test | Diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|

| Coat brushing | Ectoparasites, especially fleas, lice, surface mites, ticks, dermatophytes | |

| Skin scraping | Ectoparasites, especially Sarcoptes scabiei, Demodex spp. | |

| Tape strip microscopy | Ectoparasites, especially surface mites, dermatophytes | |

| Bacterial culture | Resistant bacterial infection(meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, Pseudomonas spp.) | |

| Wood's lamp examination | Microsporum canis infection only | |

| Fungal culture | Dermatophyte infection, yeast overgrowth | |

| Trichogram | Telogen excess, follicular dysplasia, self trauma, ectoparasites | |

| Cytology | Tape strip | Bacterial or yeast overgrowth, inflammation, neoplasia |

| Direct smear | Auto-immune disease, inflammation, infection, neoplasia | |

| Skin biopsy | Deep infection, immune mediated disease, genodermatoses, neoplasia | |

For tests to contribute to the diagnostic effort, they must be performed at an appropriate time in the timeline of the condition, and factors limiting their usefulness must be minimised. For example the presence of secondary bacterial infection will significantly reduce the value of skin biopsies; such infection should be treated before biopsy (Miller et al, 2013).

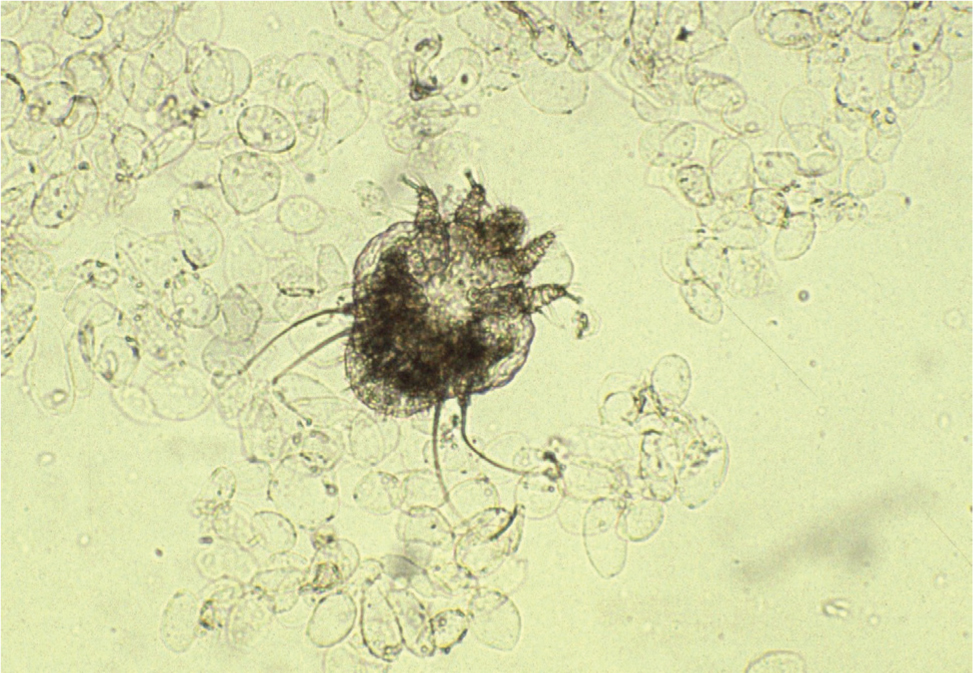

When tests are used to confirm parasitic conditions, it is essential to know which sites are most likely to yield positive results (for example, taking skin scrapings from pinnal margins when searching for Sarcoptes scabiei mites in dogs — Figures 12 and 13). Taking coat brushings for fleas or their faeces are rarely positive just after the animal has been shampooed.

The techniques, application and limitations of diagnostic tests in dermatology will be discussed in depth in the third of these papers.

Final diagnosis

Taking the information gleaned from the history, clinical examination, differential diagnosis list and diagnostic tests, a final diagnosis can usually be reached. This must consider secondary factors (e.g. bacterial or fungal infection) as these may have to be treated for the successful management of the primary problem (e.g. atopic dermatitis).

Should management of the dermatosis be less successful than anticipated, having a structured approach to diagnosis allows review of the process in the event that diagnostic signs have been overlooked.

Conclusions

A structured approach to canine and feline dermatoses is the most efficient way of making an accurate diagnosis leading to successful management.

KEY POINTS

- Careful history taking is essential for accurate diagnosis.

- Examination of both the skin and other body systems is necessary.

- A differential diagnosis list should include all possible options.

- Many diagnostic tests are simply performed in the clinic.