Intestinal roundworms such as ascarids, hookworms and whipworms can contribute to intestinal disease. Identification of worm infections in these cases is important because heavy burdens can influence both the severity of clinical signs and intestinal pathology. Regular deworming of cats and dogs is also a fundamental component of preventative health programmes for UK pets. Treating intestinal roundworms four times a year is likely to keep worm burdens low and reduce zoonotic Toxocara spp. ova output (Wright and Wolfe, 2007; Nijsse et al, 2015). As a result, it is the minimum treatment frequency for intestinal roundworms recommended by the European Scientific Counsel for Companion Animal Parasites. However, monthly treatment is often required to minimise human and animal health risk. This is the case to prevent Toxocara spp. shedding in cats and dogs likely to have high worm burdens or that live with people at high risk of infection. It is also required in dogs whose geographic location and lifestyle puts them at high risk of Echinococcus granulosus infection.

Role of worms in cases of intestinal disease

Tapeworm and ascarid infections are generally well tolerated. Large burdens can lead to intestinal obstruction, and migrating Toxocara larvae can cause respiratory signs in puppies and kittens. Hookworms are more likely to cause or contribute to clinical disease. Diarrhoea, weight loss and anaemia are the most common clinical signs and, in the case of Ancylostoma caninum in dogs and Ancylostoma tubaeforme in cats, the diarrhoea may contain blood. Skin lesions can appear on the pads of dogs and cats caused by larval penetration. All Ancylostoma species can also cause significant anaemia when present in high numbers or over a period of time. This can be severe and life threatening in puppies infected by lactogenic transmission. Uncinaria stenocephala is the most common hookworm found in UK dogs (Wright and Wolfe, 2007; Wright et al, 2016) and is less pathogenic than Ancylostoma spp. However, it can contribute to or cause diarrhoea and gut malabsorption (Miller, 1968).

The whipworm Trichuris vulpis is uncommon in UK dogs but can cause outbreaks of disease in kennels and breeding establishments, where a build-up of infective eggs in the environment can lead to heavy worm burdens. These infections can lead to colitic diarrhoea, weight loss, tenesmus and less commonly, rectal prolapse (Mohan et al, 2022). If relevant clinical signs are present, then diagnostic tests should be performed for intestinal worms. Resulting clinical signs can be vague and similar to gastrointestinal signs associated with other diseases.

The role of routine testing for intestinal helminths

One survey carried out in the UK demonstrated that 97% of dogs and 68% of cats in the UK have a relevant risk factor that may make monthly deworming necessary (McNamara et al, 2018). Risk factors for dogs include:

Risk factors for cats include:

Concerns regarding anthelmintic resistance and environmental contamination have led to the question of whether regular testing of pets could replace monthly preventative treatment in these cats and dogs. This approach has a number of drawbacks:

For testing to replace monthly treatment in high-risk groups, it would need to be performed at least quarterly – ideally monthly – to avoid prolonged human exposure to zoonotic life stages if shedding occurs between tests. Achieving high levels of compliance at this frequency would be difficult for the reasons described. Routine testing instead of treatment is a viable option where owners are reluctant to routinely treat and are positively invested in frequent testing. Testing alongside routine treatment has a number of important benefits which can be achieved through faecal diagnostics once or twice a year.

Demonstration of compliance and efficacy

Routine faecal testing alongside treatment demonstrates the value of routine treatment programmes. Regular negative tests in pets on routine preventative treatments shows good efficacy of the treatments being used and compliance on the part of the owner. This results in positive reinforcement and builds confidence in both the current recommendations and the owner's administration of the product. Positive results in pets on routine treatment may be because of issues with owner compliance, mechanical causes of treatment failure (vomiting after tablet application, tablets not being eaten in food, spot on applications being washed off, inadequate treatment frequency etc) or anthelmintic drug resistance.

Early detection plays a vital role in limiting the spread of anthelmintic drug resistant worms. This was demonstrated in the USA where multiple drug resistant Ancylostoma caninum spread rapidly from intensively dewormed greyhounds in racing kennels to domestic settings when they were rehomed (Marsh and Lakritz, 2023). A similar phenomenon could easily take place in intestinal worms of cats and dogs in the UK and go undetected because little routine faecal testing is currently taking place

Monitoring parasite distributions and geographic risk

Whether routine deworming is required in dogs for parasites present in endemic foci such as E. granulosus depends on geographic location as well as lifestyle factors. For E. granulosus, routine prevention is essential in its known endemic areas of Herefordshire, mid-Wales and the Western isles of Scotland. Surveys of abattoirs and hunting dogs in Britain suggest there are endemic foci in other parts of the country. The location of these is currently uncertain and as such, outside of these known endemic areas, lifestyle factors (access to raw offal or livestock carcasses) alone are currently recommended to inform the need for preventative treatment. The increasing availability of faecal polymerase chain reaction testing alongside the ongoing development of faecal antigen tests means that, in the future, routine testing will help to indicate if the parasite is present in an area and whether dogs require preventative treatment.

Tests performed once or twice yearly alongside treatment should be highly sensitive and specific to maximise the chance of parasites being found if present, but not misdiagnosed. There is an opportunity to spread the cost of testing by incorporating it into practice health plans. Promoting the benefits of testing to clients is vital if good compliance is to be achieved. This may be achieved through education at nurse consults, through social media and through blog posts on websites. It is important that all staff are trained on the value of testing and that the message given to pet owners is consistent.

Faecal tests available

A variety of diagnostic tests for canine and feline helminths are available, which can be run in practice or sent to external laboratories. The costs of diagnostic tests is variable depending on whether they are performed in-house or externally, among other factors.

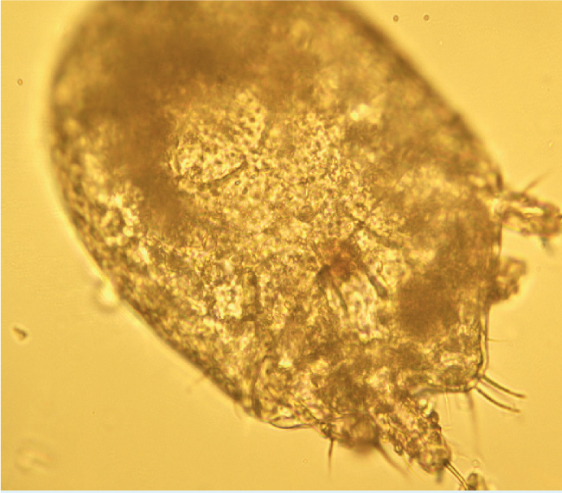

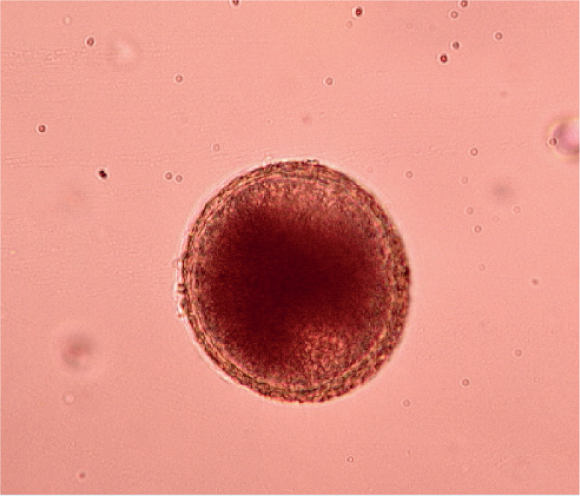

Faecal smears and flotation

Many parasites intermittently pass ova, cysts or larvae in the faeces, which can then be detected by faecal analysis. Shedding of larvae and ova is often intermittent so ideally, samples should be collected over 3 consecutive days for increased diagnostic sensitivity. If the sample is collected by the client, it must be picked up as soon as it is passed. If left on the ground, faeces rapidly become contaminated with free living nematodes (Figure 1) and mites (Figure 2). These may be confused with parasitic life stages and will also obscure the field of view during microscopic examination if present in large numbers. Once collected, samples should either be examined immediately or stored at 4°C (eg in a fridge) to prevent hatching of ova or larval development. Toxocara eggs (Figure 3), hookworm eggs (Figure 4) and Trichuris eggs may all be detected by faecal examination methods. Hookworm eggs will rapidly larvate (Figure 5) and hatch if faeces are left at room temperature.

Direct smear

Direct smears only analyse very small volumes of faeces and as a result, are considered too insensitive for the detection of helminth ova. Direct smears are useful as an initial screen for lungworm larvae such as Crenosoma vulpis and Angiostrongylus vasorum, with a sensitivity of 54–61% (Humm and Adamantos, 2010). This technique is not recommended for intestinal helminth screening.

Faecal flotation

This technique allows much larger volumes of faeces to be examined by concentrating ova present in the faeces in small volumes of liquid, while eliminating debris. Faecal flotation may still have diagnostic sensitivities as low as 60% for some roundworm ova such as Toxocara spp. and has poor sensitivity for tapeworm egg detection (Wolfe et al, 2001). Sensitivity increases with pooled samples over 3 days. It is important to know whether dogs are coprophagic before testing as this can lead to false positive results. Strongyle eggs in ruminant and horse faeces will pass through the digestive tract of cats and dogs unchanged, giving the impression that the pet is infected with hookworm. Similarly, Toxocara cati eggs may be found in dogs that have eaten cat faeces.

Many different flotation methodologies are described in the literature. A summary of the technique can be found in European Scientific Counsel for Companion Animal Parasites diagnostic guideline 4 (European Scientific Counsel for Companion Animal Parasites, 2024).

Coproantigen testing

Faecal antigen testing is commercially available in the UK for intestinal roundworms, hookworms, whipworm and the tape-worm Dipylidium caninum. These tests allow infections to be detected when ova shedding is not occurring and avoids false positive results which occur as a result of coprophagia. However, they give no indication as to what extent ova shedding is occurring.

Polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase chain reaction testing, like faecal antigen testing, has a high sensitivity and specificity for roundworm and tapeworm detection, while also allowing speciation in some cases. It also does not assess egg shedding, just the presence of the parasite, and is becoming more commercially available in the UK (Leutenegger et al, 2021).

Conclusions

In the UK, the focus of worm prevention in cats and dogs has traditionally been routine treatment for worms. As a result, there is often a prevailing feeling that routine testing is made redundant by these strategies and that testing should only be used to replace them. However, treatment and testing are not mutually exclusive, and routine testing supports and emphasises the need for the treatments used to control helminth infections. Routine testing also produces data for individual practices and local regions to help inform geographic risk when deciding which parasite control regimens are necessary. Routine testing is also vital for the early detection of anthelmintic drug resistance. Identification of intestinal worms in cases of gastroenteritis also helps to inform whether anthelmintic treatment in individual clinical cases is required.