The fear of loud and sudden noises is a well-known problem for many companion and working dogs. Dogs may react to everyday noises such as the rattling of kitchen utensils or vacuum cleaners, traffic noises and construction work, and weather phenomena such as rain, thunder and wind. The most frequent fear reactions are reported to happen when the dogs are exposed to (unexpected) sudden and loud noises such as fireworks, gunshots, thunder and roaring traffic noises (Sherman and Mills, 2008; Storengen and Lingaas, 2015; Salonen et al, 2020). Commonly displayed fear-related behaviours include (Overall et al, 2001; Blackwell et al, 2013; Tiira et al, 2016; Handegård et al, 2020):

- Trembling or shaking

- Attention seeking

- Hiding

- Vocalising

- Panting

- Drooling or licking

- Destructiveness

- Restlessness

- Indoor toileting

- Self-mutilation

- Refusal of food or water.

Owners of the most noise-reactive dogs report that the dogs may display these behaviours in the hours before events with large fireworks displays, such as on New Year's Eve (Handegård et al, 2020).

Understanding the genetic background of noise reactivity in dogs can help breeders make informed decisions to reduce the prevalence of noise-related behavioural issues in specific breeds. It can also shed light on behaviour modification strategies for affected dogs, potentially leading to more effective interventions. For example, knowledge of specific genetic markers associated with noise reactivity could enable targeted therapies or medications. However, genetic studies on noise reactivity are not straightforward.

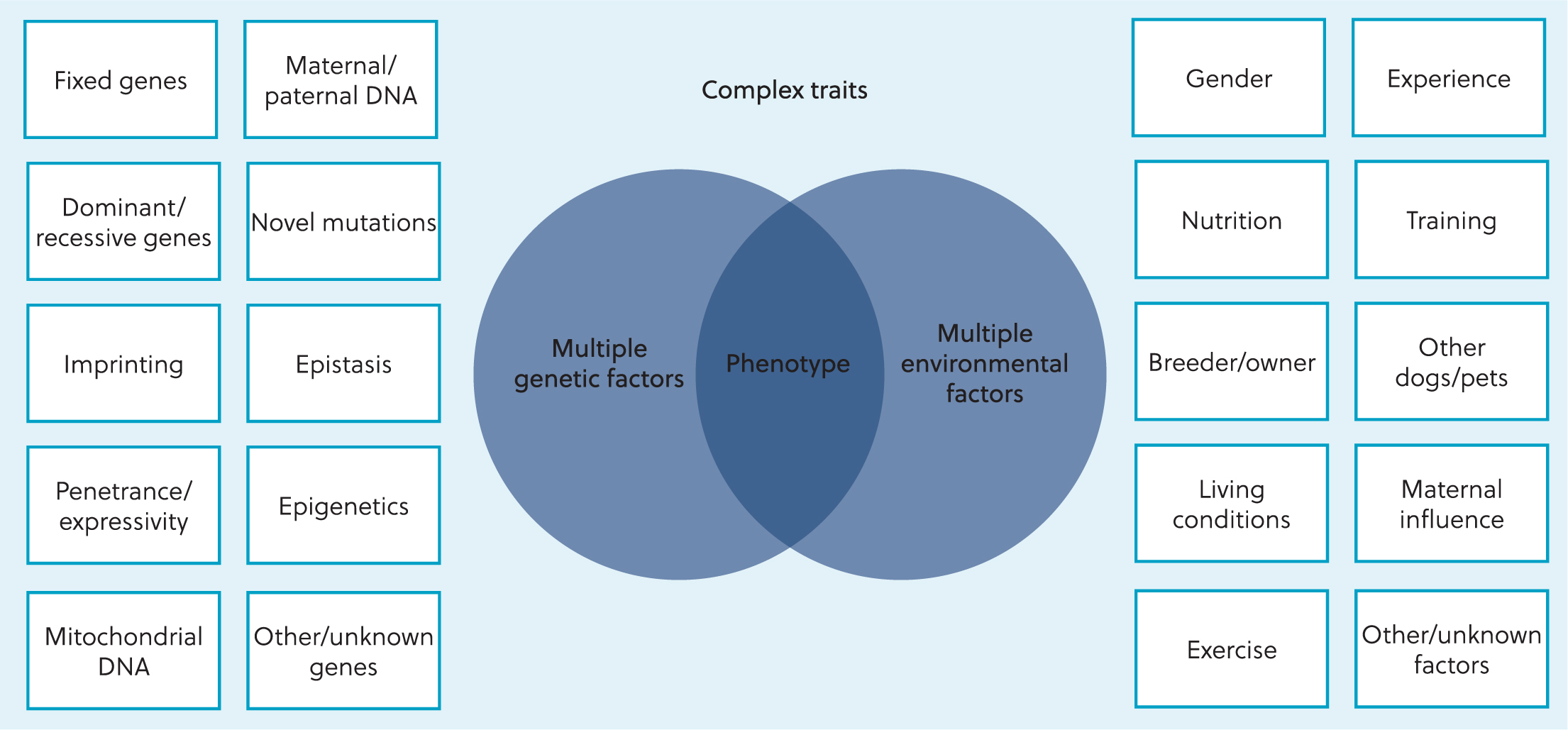

Noise reactivity, like other behaviour traits, is complex. There is huge variation in phenotype presentation; dogs may be fearful of all, just one or a few very specific noises, and display a range of different behaviours, from a slight tremble to complete panic. Complex traits are affected by a combination of genetic factors, environmental factors and life experiences (Blackwell et al, 2013), where the importance and value of the individual effects are unknown and/or variable (Figure 1). For example, studies have found that factors such as gender, age, castration status, early experiences and the owner's gender may be important in the development of noise reactivity (Blackwell et al, 2013; Tiira and Lohi, 2015; Cannas et al, 2018; Salonen et al, 2022). It has also been suggested that some noise-reactive dogs suffer from musculoskeletal pain, pain in the ears and/or a change in auditory response (Scheifele et al, 2016; Tiira et al, 2016; Lopes Fagundes et al, 2018). A thorough clinical health examination is always advised in all dogs that display excessive fearfulness or any other problematic behaviour.

Studies on fear, phobia and anxiety have been conducted in numerous species, both domestic and wild animals, as well as laboratory animals; however, no consistent definition of fearfulness as a behavioural trait exists in veterinary medicine (Mobbs et al, 2019). Different literature, as well as different veterinarians and behaviourists, uses terminology like ‘noise reactivity’, ‘noise aversion’, ‘noise sensitivity’, ‘noise phobia’, ‘noise anxiety’ and ‘fear response to noise’ to describe, at least partly, the same phenomenon of dogs showing abnormally strong reactions to all or specific noises (Stephens-Lewis et al, 2022).

Fear, phobia and anxiety have different definitions, but in everyday speech among dog owners and veterinarians, these terms are very often mixed and used interchangeably. Similarly, there is a spectrum of different approaches to behavioural assessment in dogs, including battery testing, owner-directed survey and expert breed assessment (Jones and Gosling, 2005; Spady and Ostrander, 2008). These tests are often adapted to different breeds, ages and purposes; for example, the ‘dog mentality assessment’, the ‘behaviour and personality assessment’ and the ‘public access test’. Special tests have been adapted for puppies with the purpose of selecting the best-qualified individuals for future training. The results of such tests may then be used to select breeding animals, potential working dogs or assess the heritability of different personality traits (Wilsson and Sundgren, 1997; Ruefenacht et al, 2002; Lazarowski et al, 2021). Likewise, different versions of questionnaires have been developed: the most frequently used to date is the canine behavioural assessment and research questionnaire (Hsu and Serpell, 2003). This lack of unified terminology and standardised, well-validated behaviour recording schemes makes it difficult to compare data between studies, thus making epidemiological studies of both genetic background and treatment of behavioural problems in dogs very challenging (Overall, 2013). The great majority of noise-reactive dogs never undergo a behaviour test, and relatively few owners seek professional help for noise-reactive dogs (Rugbjerg et al, 2003; Dale et al, 2010; Blackwell et al, 2013).

Genetic background of noise reactivity

Genetic mutations occur in different parts of the genome all the time, and cause genetic differences between individuals, populations and species. Some mutations may be beneficial and provide a selective advantage to individuals carrying them, which leads to the spread of those mutations in a population. When a particular beneficial mutation becomes fixed, every individual in the population possesses that mutation. In genetics, an allele is a variant form of a gene. When an allele becomes fixed in a population, every individual in that population has that allele for a specific gene. In wild animals, this typically occurs through the process of genetic drift or natural selection. In modern dog breeds, artificial selection of specific traits (beneficial or not) has created breed-specific fixed alleles, which makes it possible to distinguish one breed from another through DNA tests. Phenotypically, all dogs of the same breed have the same unique characteristics that identify the breed – they are observed as fixed traits. One of the key characteristics of a fixed trait is the absence of significant variation within a population. In other words, individuals within the population tend to have similar genetic makeup regarding that specific trait.

Fearfulness and other behaviour traits are likely highly polygenic, meaning they are controlled by a large number of gene alleles which all have small effects. It is also very likely that many of these alleles are fixed in the population. Noise reactivity occurs in all purebreeds and mixed breeds, which is no surprise given the fact that fear, including fear of noises, is a natural trait and an essential part of natural selection and survival skills (McFarland, 1981; Erhardt and Spoormaker, 2013; Ressler, 2020). Fearfulness, by nature, is a very useful trait. Fear makes animals (and humans) keep a safe distance from things that may be harmful, and thus is a trait that has been very beneficial for dogs for many generations before they became domesticated. In some cases, however, the fearfulness becomes more severe than ‘normal’ and may ultimately negatively impact the dog's welfare and the dog-owner relationship, and the behaviour may then be classified as pathological (Overall, 2013). The impact of extreme fearfulness in dogs can be huge, both for the individual dog and animals and humans it interacts with (Rugbjerg et al, 2003; Shore, 2005; Cannas et al, 2018), and may have a profound negative impact on the dog's life expectancy (Scarlett et al, 1999; Dreschel, 2010). While noise reactivity may not directly determine a dog's lifespan, the stress and anxiety associated with such traits could potentially contribute to health issues that may impact longevity. Additionally, dogs may be more prone to accidents or injuries if they display extreme fear reactions, for instance by running away from the owner. Dogs that are overly sensitive to noise may have a reduced quality of life if they are constantly distressed by their environment, and if the problem becomes impossible to manage the owner may opt for euthanasia or rehoming.

Studies show that there are significant breed differences in the prevalence and severity of noise reactivity. In some breeds, as many as 30% show a strong or very strong fear of loud noises, and more than 50% may show some signs of noise reactivity (Blackwell et al, 2013; Storengen and Lingaas, 2015; Tiira et al, 2016; Riemer, 2019; Handegård et al, 2020; Salonen et al, 2020). This difference between breeds suggests a relevant genetic component to noise reactivity (Morrow et al, 2015; Storengen and Lingaas, 2015; Overall et al, 2016) which may be explained by selective breeding; for example, gun shyness is not a favourable trait in hunting dogs, while guard and herding dogs may exhibit height-ened vigilance and reactivity as a result of their historical roles as guardians and protectors.

Many studies on behaviour have been conducted as heritability studies. Heritability is measured from 0 to 1, where 0 is low and 1 is high. Heritability estimates indicate how much of the phenotypical variation in a population can be explained by genetic variation or in other words: how much of the phenotypical variation cannot be explained by environmental factors or by chance. Thus, heritability must not be confused with heredity. Environmental factors are likely to play a big role in the development of behaviour problems, including excessive fear. However, heritability estimates of non-social or noise-related fear show that these behaviours also have a significant genetic component (Table 1). This indicates that it should be possible to reduce the prevalence of reactivity to loud noises through the systematic breeding of less fearful dogs.

Table 1. Heritability (narrow) for a selection of noise/fear-related behaviour traits in dogs

| Trait | Heritability (h2) | Breed |

|---|---|---|

| Curiosity/fearlessness | 0.23 | German shepherd dog |

| Fear | 0.46 | Guide dogs (Labrador retriever) |

| Firework fear | 0.16 | Standard poodle |

| Gun shyness | 0.56/0.21 | Labrador retriever/German shepherd dog |

| Gunfire reaction | 0.19/0.23 | German shepherd dog |

| Gunshot fear | 0.37 | Flat coated retriever |

| Non-social fear | 0.27 | Golden retriever |

The within-breed and between-breed variation in prevalence and presentation of noise reactivity, combined with low–medium heritability estimates, suggest the existence of causative genetic variants. Many studies have been performed in search of such variants but with limited success, probably because of the nature of complex traits. Genome-wide association studies have identified some candidate genes that may be of interest for several complex traits, including behaviour-related traits such as canine obsessive-compulsive disorder, sociability and fearfulness (Dodman et al, 2010; Tang et al, 2014; Persson et al, 2016; Zapata et al, 2016; Sarviaho et al, 2019; 2020; Shan et al, 2021). The development in gene technology is progressing fast, and genome-wide association studies are now being rapidly replaced by more modern methods such as whole genome sequencing, third-generation sequencing and low-pass sequencing. Almost everything that is known about the canine genome has been discovered in the past 20 years, and many more discoveries should be expected to unfold over the next decades.

Animal welfare

Fear, phobias and anxiety are negative emotions that may have a significant effect on the welfare of dogs (Sherman and Mills, 2008; Bovenkerk and Nijland, 2017). In selected breeds, around 50% of dog owners report that their dogs show some sign of fear when exposed to loud and sudden noises, such as fireworks (Blackwell et al, 2013; Handegård et al, 2020), which makes it one of the most extensive welfare issues for companion dogs. For 10–50% of relinquished dogs, the owner states that behaviour issues are part of the reason why they feel unable to keep the dog (Marston et al, 2004; Kwan and Bain, 2013; Salonen et al, 2020); most of these dogs are younger than 3 years old (Kwan and Bain, 2013). These findings are supported by two studies based on veterinary records which found that undesired behaviour was the predominant cause of mortality for dogs aged 3 years or younger (Boyd et al, 2018; Yu et al, 2021). Fear-related behaviour is also a common reason for dogs being released from guide dog training programmes, withdrawn after successful guide dog training (Batt et al, 2008; Caron-Lormier et al, 2016) and in discharged adult military dogs (Evans et al, 2007). A positive association has been found between noise reactivity and other serious behavioural problems, including aggression, separation anxiety and general fearfulness (Overall et al, 2001; Tiira et al, 2016; Salonen et al, 2020), which are in themselves well-known reasons for euthanasia and relinquishment. It has also been documented that many dog owners are unaware of the possibility of behaviour modification and pharmaceutical treatment of firework fear (Blackwell et al, 2013). Habituation, training and psychopharmaceutic intervention have well-documented effects on fearfulness in dogs, so owners should be encouraged to seek professional help and advice.

Conclusions

Noise reactivity is a profound problem for many dogs and the fear reactions are often severe. To date, little is known about the genetic influence on fear, or why specific noises such as fireworks cause extreme fear reactions in some dogs. It is difficult to claim that all dogs with some degree of noise reactivity have reduced animal welfare. However, with evidence that noise reactivity has a relevant hereditary component, it may be advisable to recommend that seriously affected dogs should not be used for breeding, which over time can help reduce the prevalence of noise reactivity in the breed. Continued research on canine fear and behaviour promises to improve understanding of noise reactivity, ultimately benefiting the welfare of dogs and enhancing the bond between humans and their canine companions.

KEY POINTS

- Canine behaviours are complex traits.

- Noise reactivity and firework fear have a genetic component.

- Severe noise reactivity can pose a welfare issue in dogs.

- Systematic breeding can reduce the prevalence of noise reactivity.