Examination of the oral cavity may prove difficult in an awake patient. The patient may be anxious or frightened during veterinary visits potentially leading to aggression (Rodan et al, 2011). Determining if a cat has oral inflammation or oral pain may require a brief glance into the oral cavity or taking a history from the owner. Given those challenges, the veterinarian may determine that the soft tissues of the mouth are erythemic without knowing the reason or severity. This may lead to misdiagnosis of the issues and resulting improper treatment.

The feline mouth can be affected by many disorders that all lead to inflammation of the oral gingiva and mucosa. The inflammation can be further characterised by its duration, recurrence, location and appearance (Lommer, 2013). Additionally, understanding the aetiologies that effect certain life stages of cats and those with concurrent disease can lead the practitioner in the appropriate direction. Knowing the underlying cause is necessary for treatment; this article will discuss some of the more common feline inflammatory aetiologies, their diagnosis and treatment options.

Periodontal disease

Periodontal disease is the most common disease in companion dogs and cats, affecting 80–85% of animals at 2–3 years of age (Stepaniuk, 2019). This disease is caused by subgingival bacterial plaque, and the inflammatory response to it continues as long as the soft tissues are exposed (Slots, 1979). There are two general categories of periodontal disease: gingivitis and periodontitis. Gingivitis is the first stage of periodontal disease where the inflammation is located only at the gingiva. Gingivitis becomes periodontitis once the disease progresses to deeper inflammation, which can cause the loss of the tissues that support the teeth.

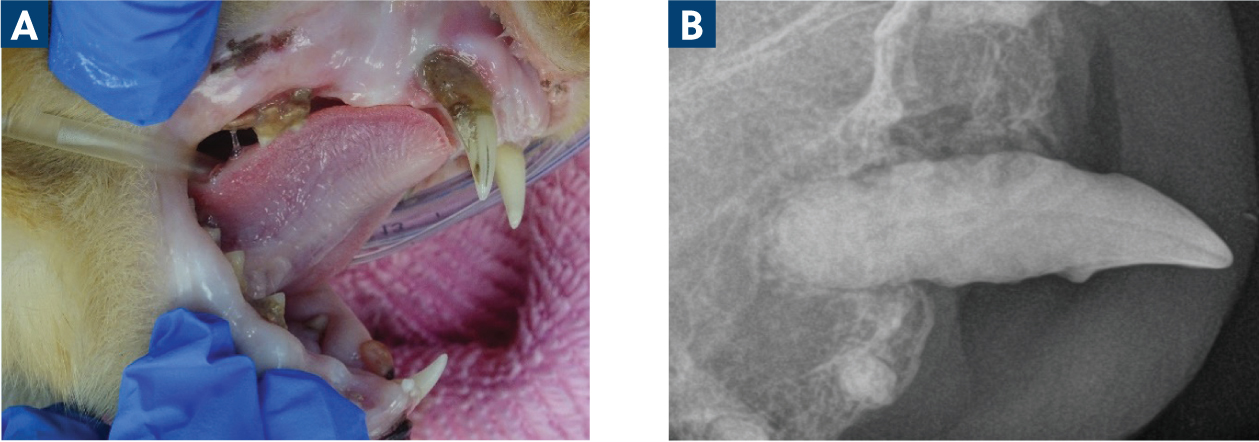

Normal gingiva is a pink colour with a sharp, well-defined edge and smooth surface (DeBowes, 2010). The earliest sign of gingivitis was thought to be a colour change (redness) at the gingival margin (Niemiec, 2013a) (Figure 1). This must be separated from the erythema caused by the vasodilation in the soft tissues as a result of situational stress. It is now known that an even earlier sign is bleeding on brushing, playing with toys or probing of the gingiva (Niemiec, 2013b). Once these signs occur, there is an opportunity to reverse the process without bone or tissue loss. However, the presence of calculus is not a predictor of disease progression as it is relatively non-pathogenic, mostly causing an irritant effect (Niemiec, 2016).

Once the disease has progressed to periodontitis, clinically detectable attachment loss is present. The oral inflammatory changes may include an increase in the intensity of the inflammation (erythema, oedema and haemorrhage). The attachment of the tooth to the periodontium progresses toward the apex of the tooth root, creating an increased periodontal pocket depth or, in some cases, gingival recession. During this migration, alveolar bone is lost; this clinical situation is not reversible without specialist-level regenerative procedures (Figure 2). Obvious clinical presentations of the attachment loss are extreme halitosis, gingival recession, the creation of deep periodontal pockets, tooth mobility and tooth exfoliation. Once the tooth is exfoliated, the tissues can return to an uninfected status (Stepaniuk, 2019). Periodontal disease has some localised effects including oronasal fistulas, pathological bone fractures and osteomyelitis. Additionally, it has been associated with systemic effects, such as organ fibrosis and oral neoplasia, as well as making the treatment of chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus more difficult (DeBowes, 1998; Cave et al, 2012; Niemiec, 2016).

Diagnosis of these conditions involves regular veterinary oral health examinations. When indicated, anesthaetised oral examinations with dental probing to assess the distance from the cementoenamel junction to the attachment of the gingiva should be performed. Additionally, dental radiography is critical in assessing the amount of alveolar bone support that remains. Both of these tools are necessary to further characterise the disease and plan treatment for each tooth (Stepaniuk, 2019). Treatment of periodontal disease includes thorough removal of plaque and calculus, root planing (open and closed) and, in appropriate cases, tooth extraction (Niemiec, 2016). These processes must be performed under general anaesthesia to be effective and safe for the patient and veterinary staff (Bellows et al, 2019).

Periodontal disease can be prevented, or at least managed, with appropriate home care involving regular and consistent removal of the plaque biofilm. Client education and recommendation of effective products and processes is key. Regular anaesthetised professional dental exams, full mouth radiographs and cleanings must be performed throughout the cat's lifetime at intervals directed by a veterinarian to meet the needs of the individual patient. These home care tools and appropriate expectations should be established by veterinary professionals at kittenhood (Bellows et al, 2019).

Early onset gingivitis and aggressive periodontitis

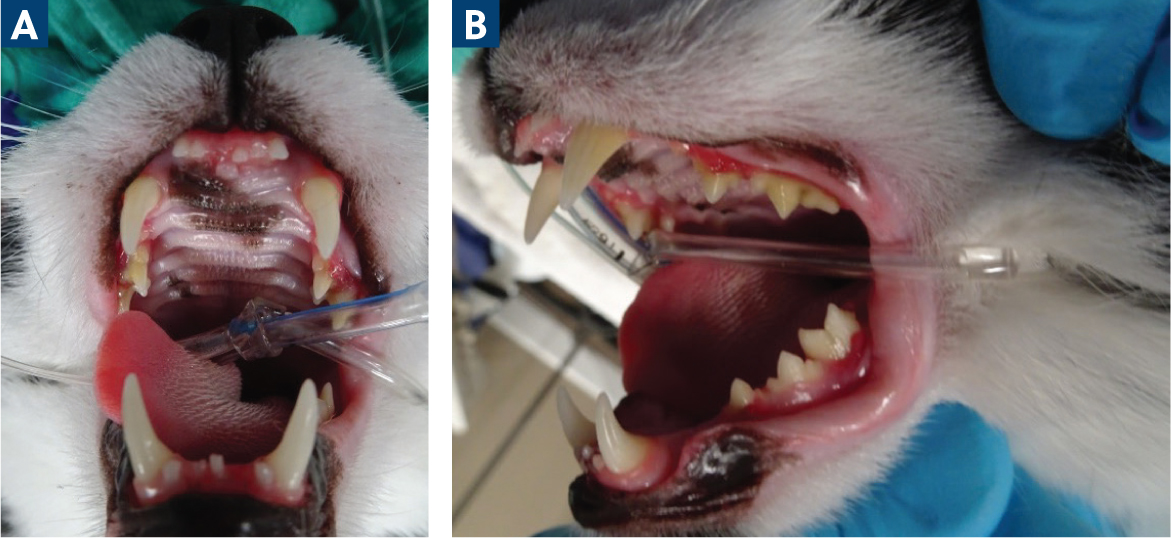

Early onset gingivitis, historically known as feline juvenile hyperplastic gingivitis, occurs in cats around 6–8 months of age (Shope et al, 2019). The incidence and aetiology of this disease is currently unknown; however, the disease has recently been further characterised (Soltero-Rivera et al, 2023a). The clinical presentation is marked gingival inflammation with bleeding on examination and mastication. This disease may be seen with or without gingival enlargement (Reiter, 2018). This condition can occur in any cat breed, though there appears to be a predisposition in Siamese, Somali, Maine-Coon, Persian and Abyssinian purebreds (Shope et al, 2019). Patients may require removal of subgingival plaque every 3–6 months, along with routine homecare, to manage the gingivitis and attempt to resolve the symptoms (Shope et al, 2019).

Even with treatment, this disease may progress to aggressive periodontitis (Girard et al, 2009), which is characterised by the deeper extension of the inflammation, leading to periodontal pocket format, gingival recession and tooth loss (Shope et al, 2019) (Figure 3). These cats present with marked halitosis and gingival inflammation that spreads to the attached gingiva (Bellows, 2010). Soltero-Rivera et al (2023a) found that 78% of cats with moderate-to-severe early onset gingivitis showed evidence of radiographic periodontal disease. Treatment for the cats in this study involved sub- and supragingival scaling and selective tooth extraction. Cats that did not show improvement in their clinical signs or in the severity of the gingivitis at a 2-week recheck visit were significantly at risk for disease progression (Soltero-Rivera et al, 2023a). The gingivitis and periodontitis may progress to a diffuse oral inflammatory disease involving the gingiva and mucosa, known as feline chronic gingival stomatitis.

Oral exams should be performed in cats as early as 6 months of age (Soltero-Rivera et al, 2023a). There is an opportunity to perform this exam at the 6-month feline viral rhinotracheitis, calicivirus and panleukopenia vaccine booster and determine whether a kitten is exhibiting extensive gingivitis, as many of them are asymptomatic and this may not be noticed by owners. Those identified will need an exam under anesthaesia, periodontal treatment and monitoring. Clients must be educated about the potential need for immediate and future tooth extraction. Biopsy and histopathology should also be performed in cases with substantial gingivitis with or without enlargement to differentiate hyperplasia from other pathologies (infectious, tumors) that may involve different or further treatment.

Tooth resorption

There are many theories regarding the aetiology of tooth resorption, these are not entirely evidence-based (Reiter et al, 2005). At least one-third of cats develop tooth resorption during their life-time, and the risk of developing tooth resorption increases with age; it is rarely seen in cats less than 2 years of age (Ingham et al, 2001). The first mandibular cheek tooth or the mandibular third premolar are most often affected, followed by molars and canines (Mestrinho et al, 2013). In this disease, odontoclasts that are normally responsible for remodelling bone are activated and do not deregulate, andodontoblasts do not replace the tooth structure. Although this can initially be asymptomatic when located apical to the gingival margin, the inflammatory process is initiated once it progresses coronally. Exposure of the sensitive nerve endings causes pain, so owners may report ptyalism, reluctance to eat hard food, teeth grinding or chewing on unusual materials among other signs of oral pain (Frost and Williams, 1986).

Inflamed, hyperplastic gingiva or pulp tissue, as well as granulation tissue, is often seen at the gingival margin during conscious oral examination. The tissue often bleeds, and chattering may occur when the teeth are probed. Under anaesthesia, a dental explorer can be used to detect abnormalities at the gingival margin. When the gingiva has grown over the root remnant after the crown has been lost in the advancement of the disease process, a bulge underneath the gingiva can be seen or palpated (Bellows, 2010).

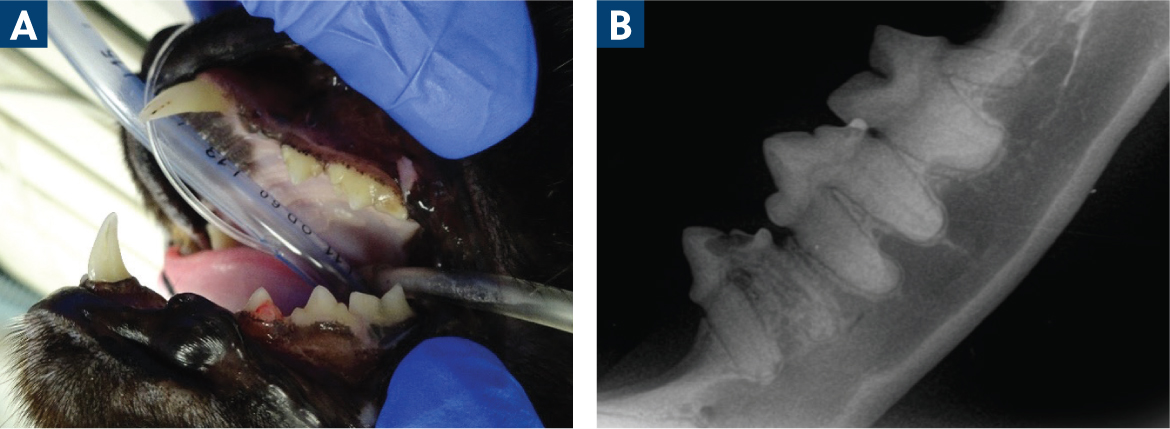

Dental radiographs are also essential in this diagnosis. Without this modality, tooth resorption below the gumline is not detectable. These lesions are sorted into two main types based on dental radiography. Type 1 tooth resorption lesions are typically associated with inflammation, as in periodontal disease or caudal stomatitis. In type 1 lesions, the root system stays intact; this results in continued discomfort and the structure lost to the resorption is not replaced by bone. By contrast, type 2 lesions are not associated with precursor inflammation and lead to replacement resorption, resulting in ankylosis. This process often continues until no recognisable structure remains on radiographs (Reiter and Mendoza, 2002; Reiter et al, 2005).

The treatment of this condition depends on the radiographic appearance of the affected tooth. By definition, all types of tooth resorption lesions will have areas of tooth or tooth root loss. Teeth with type 1 resorption will have most of their root structure and a well-defined periodontal ligament space (Figure 4). These teeth must be fully extracted (Reiter and Soltero-Rivera, 2014). Teeth with type 2 resorption will have undergone significant replacement of the root with bone, so there is narrowing or disappearance of the periodontal ligament space. A tooth with characteristics of type 1 and type 2 resorption is designated type 3 resorption (Figure 5) (Reiter et al, 2019). Areas of type 2 resorption may be treated by crown amputation as long as the tooth does not have endodontic disease, and the patient is not experiencing caudal stomatitis. This technique allows for less trauma, less time under anesthaesia for treatment and faster healing (DuPont, 2002). Because of the progressive nature of this disease, regular radiographic monitoring should be performed in order to treat the mouth before pain and inflammation ensue.

Feline chronic gingivostomatitis

Feline chronic gingivostomatitis encompasses a range of clinical presentations from the most severe inflammation of the whole oral cavity to more focal presentations limited to specific tissues and locations (Reiter et al, 2019). The condition can include inflammation and ulceration of the oral cavity and oropharynx or may be more isolated only in the tissues lateral to the palatoglossal folds (caudal mucosa). The actual cause of the condition is not known; multiple aetiologies likely act in combination to create the inflammation (Reiter et al, 2019). The cat's response to bacterial infection, environmental factors and genetics in combination with viral infections all likely influence the condition. The oral flora of affected felines appears to be less diverse (predominance of Pasteurella multocida spp. multocida) and the immune response is exaggerated (Dolieslager et al, 2011). Increased stress, as in colonies or multicat households, appear to be environmental factors that may increase occurrence as well as provide close density to enable disease spread (Peralta and Carney, 2019). Overall, the published literature supports the role of feline calicivirus in at least modulating the severity of this disease (Soltero-Rivera et al, 2023b).

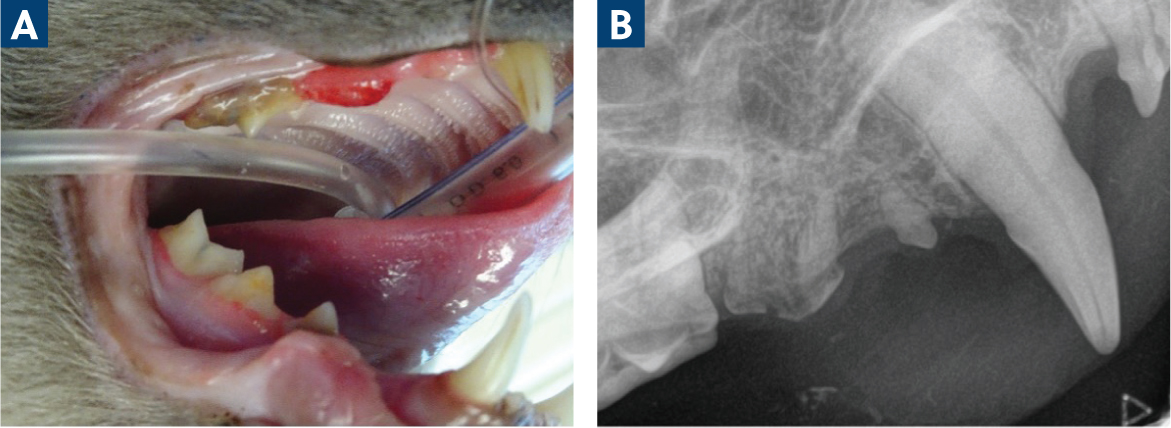

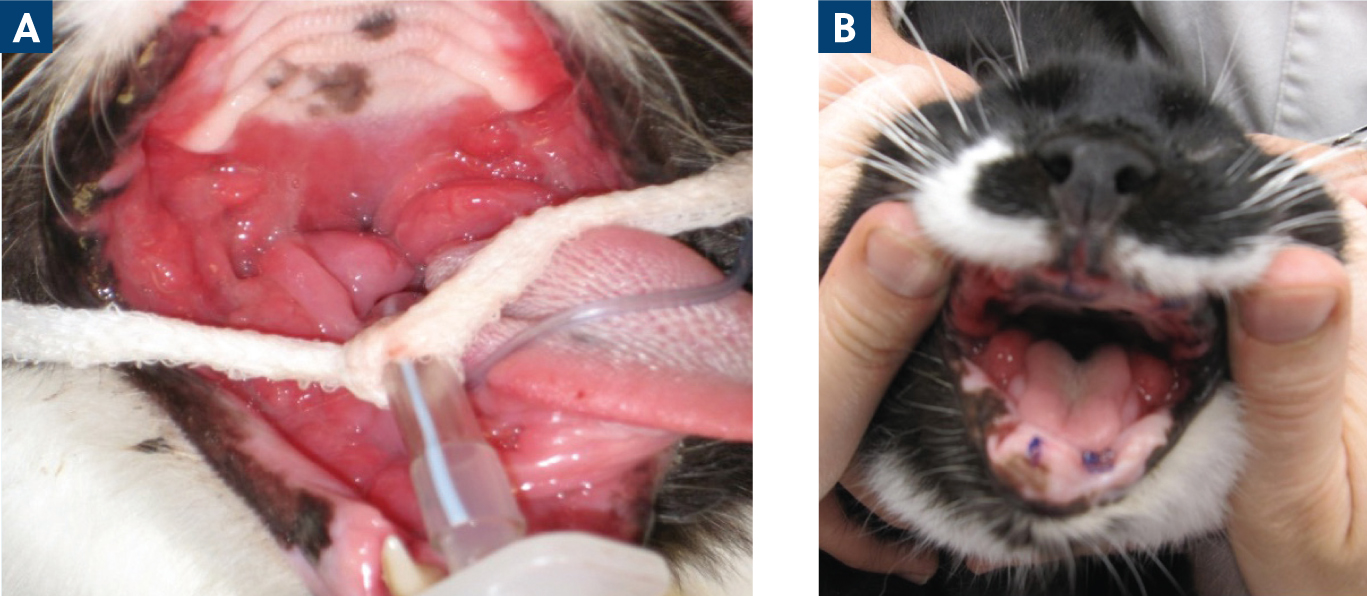

Cats affected by this condition tend to be older than those with juvenile periodontitis, with a mean age of about 7 years (Johnston, 2012). Cats may present with obvious halitosis, pain on eating, ptyalism, weight loss and decreased activity levels. Alternatively, they may present with a lack of clinical signs but still have extensive levels of inflammation and ulceration. The most severely affected cats present with alveolar mucositis (inflammation of the mucosa associated with primarily the cheek teeth), caudal mucositis as well as sublingual mucositis (Figure 6). The pharynx, tongue and lingual molar salivary glands can also be affected in these cases (Reiter et al, 2019).

The diagnostic and treatment plans for these cats are most successful when approached early in the case progression before such exaggerated inflammation is present and clinical signs become severe. The compliance of the cat decreases rapidly in many cases, resulting in increased frustration on the part of the client. A thorough physical exam with scoring of the oral soft tissues using the Stomatitis Disease Activity Index should be performed to enable tracking of treatment results. Baseline bloodwork should be performed before anaesthesia for the remaining diagnostic work up. The most striking clinical pathological abnormalities are typically a hyperglobulinaemia and a mild basophilia (Reiter et al, 2019). Retroviral testing should be completed to ensure that there are no contraindications to therapies going forward. Under anaesthesia, a full oral exam with charting as well as full mouth dental radiographs are imperative to identify all pathology, including teeth or root tips encased in the inflammation or under the bone. A biopsy should be performed to eliminate the possibility of neoplasia as well as other disease processes that may not respond to the treatment initiated for feline chronic stomatitis.

The initial treatment early in the disease is to clean the teeth and remove any that are diseased (periodontal disease or tooth resorption). Antibiotics (mostly clindamycin or amoxicillin with clavulanic acid) may be useful at this point to allow the soft tissues to heal more successfully (Reiter et al, 2019). Daily elimination of the plaque is crucial, and a tolerated chlorhexidine product is advised. If there is improvement in 3–5 weeks, the daily plaque removal and frequent professional scaling (every 3–4 months) can continue for management. If not, all cheek teeth or all of the teeth must be removed in their entirety as soon as possible (partial mouth extraction or full mouth extraction). About 50% of the cases do not require further treatment, with another 37% only needing manageable inflammation treatment (Jennings et al, 2015). Full mouth extraction should be recommended and performed for patients with diffuse inflammation including the canines and incisors or if there is no response to partial mouth extraction, regardless of the absence of inflammation around the rostral teeth (Soltero-Rivera et al, 2023b). Postoperative analgesia, antibiotics (possibly pre and postoperative) and nutritional support are critical for recovery from multiple extractions. A short course (5 days) of antibiotics may be useful because of the intense surgery that is required for full or partial mouth extractions and the poor condition of the tissues that is often present (Soltero-Rivera et al, 2023b). The extraction of this many teeth is not to be done without a definitive diagnosis of stomatitis and an appropriate clinical practice situation (clinician skill, anaesthesia management) (Figure 7).

In cats that need further support, many therapies have been used with mixed success. Recombinant interferon, mesenchymal stem cell therapy, glucocorticoids, cyclosporine, omega-3 fatty acids, pentoxifylline-cobalamin-doxycycline combination therapy and carbon dioxide laser surgery have been tried with varying results (Reiter et al, 2019). Each patient is unique in what works best for them and their situation. It is essential that the owner is involved as soon as the diagnosis is made for the patient. They must understand the prognosis, treatment options and the need for home care. Many of these options are expensive and require owner dedication as well as the ability to administer them to their animal.

Eosinophilic granuloma complex

Eosinophilic granulomas and indolent ulcers can both occur in feline mouths. While the true aetiology of these lesions is unknown, a genetic predisposition of eosinophil regulation and hypersensitivity (to fleas, food and/or the environment) are suspected (Buckley and Nuttall, 2012). Indolent ulcers are the most common presentation, causing yellow-to brown-coloured lesions on the upper lip. The granuloma manifestation may present as lip and chin swelling or as ulcerations of the tongue, palate and palatal arches (Werner, 2016).

Diagnosis usually involves clinical signs or topical cytology; however, biopsies may be needed to be sure of the diagnosis in cases that are not confirmed with other diagnostics (Mezei et al, 1995). Dental radiographs should also be performed to rule out any bone changes or retained tooth roots. These lesions can mimic periodontal disease, stomatitis or neoplasia. Allergic evaluation should be considered by eliminating the most likely issues with a food trial and flea control (Reiter et al, 2019).

Acutely, these lesions should be treated carefully with systemic corticosteroids and occasionally antibiotics. The inciting cause should be addressed if it can be determined. These lesions are often determined to be idiopathic and require continued therapy. Since chronic use of steroids in cats has some negative effects, a tapering cyclosporine regimen has also been successfully used for treatment when finances allow its use (Niemiec, 2016).

Neoplasia and masses

Pyogenic granulomas

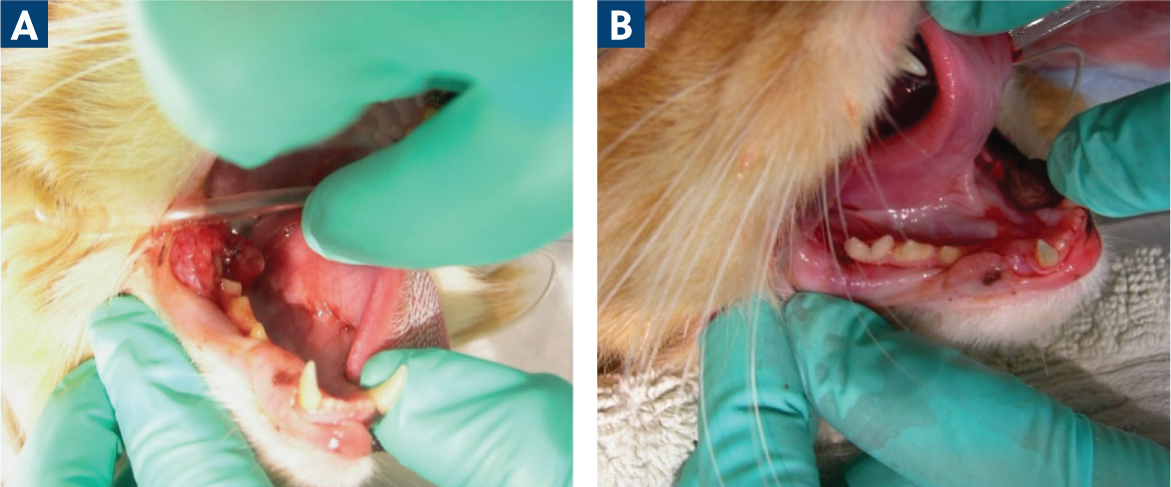

Pyogenic granulomas are reactive lesions of the gingiva or mucosa, with tissue proliferation and ulceration in response to injury. These lesions are often at the buccal mucosa of the mandibular first molar covered by a fibrinous membrane. The aetiology appears to be caused by trauma to the mucosa from the maxillary fourth premolar because of either malocclusion or previous extraction of the mandibular molar (Figure 8). Surgical excision along with the removal of the traumatising factors, such as the maxillary fourth premolar, is typically curative. Odontoplasty may also be an option to prevent or remove trauma, depending on the skill level of the practitioner (Hamilton and Hiscox, 2024). Tissue should be submitted for histopathology to confirm the diagnosis, as other differentials such as neoplasia or proliferative gingivitis have different recommendations and follow up care (Soukup and Lewis, 2019).

Neoplasia

There are many benign tumours or tumour-like lesions that can occur in the feline oral cavity. Focal fibrous hyperplasia, pyogenic granulomas, peripheral giant cell granulomas and feline inductive odontogenic tumours (rostral maxilla in young cats) can all occur in the mouth and are all inflammatory in appearance. Fortunately, these are all lesions that can be treated with excision alone to avoid recurrence (Soukup and Lewis, 2019). Feline epulides (these masses do not have the same clinicopathological features as peripheral odontogenic fibromas in dogs) can be complicated as they often have a mixture of fibromatous, ossifying and acanthomatous features in the same lesion. Additionally, they are often multifocal, making excision a challenge, and may require multiple surgeries (Soukup and Lewis, 2019).

There are neoplastic processes in the feline oral cavity that can also lead to ulceration and inflammation of the soft tissues. The most common process of concern is squamous cell carcinoma, which is usually seen in older cats at an average age of 11–13 years (Bellows, 2010). This tumour is often found at the premolar and molar regions in the maxilla, and the premolar region of the mandible. Most commonly, it can be seen sublingually or in the tonsils so can be missed on an awake oral exam (Dhaliwal, 2010; Soltero-Rivera et al, 2014). These tumours are very locally aggressive; however, when they do metastasise, it is most often to the mandibular lymph nodes (Soltero-Rivera et al, 2014). These tumors present with similar clinical signs to chronic gingivostomatitis and appear as fleshy, friable, proliferative, usually bleeding masses that are initially unilateral, but may be extensive by the time of diagnosis (Dhaliwal, 2010). They can mimic periodontitis by causing bone destruction under the soft tissues leading to tooth mobility and/or swelling that is often thought to be a tooth abscess.

After ensuring the animal is appropriate for anaesthesia, full mouth radiographs should be performed even in areas with no further inflammation to characterise what is happening in the bone. Loss of alveolar bone with irregular edges, mottled bone lysis and areas of what appears to be new bone proliferation may be evidence of neoplasia. Once the disease advances, teeth appear to be floating in the space that used to have bone (Niemiec, 2016). The radiographic diagnosis should not be considered definitive, and substantial biopsy submissions with histopathology should also be performed. Fine needle aspirates may be used tentatively, but the technique to get results that agree with histopathology can be challenging (Bonfanti et al, 2015). Ideally, an incisional biopsy will be performed for a definitive diagnosis.

After diagnosis, staging as with other malignant tumours is recommended if treatment is going to be initiated. Feline squamous cell carcinoma is difficult to treat, and survival times are reported to be anywhere from 60 days to 6 months (Niemiec, 2016). Surgical margins of 10 mm are advised; however, by the time these tumours are diagnosed, it is often too late for those to be attainable (Niemiec, 2016; Gieger and McEntee, 2020). Options for surgery with or without palliative radiation should be discussed with the surgeon and/or oncologist if these options are desired (McDonald et al, 2012). Medical management is mostly palliative, with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs giving some improvement to quality of life. More research is ongoing to provide avenues for prevention and treatment of these patients.

Conclusions

Many different causes lead to inflammation in the feline mouth. This review discussed the most common diseases leading to this condition and how to recognise, diagnose and treat them. Many factors must be considered when reaching a diagnosis for these patients, such as age, clinical signs, gross appearance, radiographic appearance and histopathology. If only a cursory exam is done before setting client expectations, over-or under-treatment may be inaccurately recommended. Cats do not always allow effective conscious oral exams and only a small portion of the oral cavity may be visualised. Giving clients the most accurate information about possible extractions, the extent of those extractions or other treatments is critical in getting a commitment from the client to help the patient. Inadequate diagnostics and inaccurate treatment may lead to young animals with full mouth extractions or animals with severe disease having avoidable consequences, such as retained tooth roots or unrecognised disease. If the general practitioner is working outside their scope of practice because of a lack of tools, such as dental radiography or anaesthetic monitoring, referral to a veterinary dentist is advised.