The 14th and 15th August saw Courageous Conversations, the UK's first veterinary diversity and inclusion conference hosted by the University of Surrey, take place online. Attendees were both staff and students from all UK vet schools as well as representatives from BVA, RCVS, SPVS and VMG. The volunteer groups British Veterinary Ethnicity and Diversity Society (BVEDS), British Veterinary LGBT+ (BVLGBT+) and British Veterinary Chronic Illness Society (BVCIS) finally had an opportunity to have interested parties together in one ‘virtual’ room to talk about the problems marginalised groups face within the veterinary profession both from our colleagues as well as the wider public.

The second day of the conference was the student-focused day. This was an appropriate forum to report on some research we have conducted at the University of Surrey looking into the types of discrimination that students have experienced or witnessed while undertaking their clinical EMS, followed by a workshop to brainstorm some solutions. The research was similar to the BVA's Discrimination Survey and the BVA Spring 2019 Voices Survey described in their report on discrimination in the veterinary profession (BVA, 2019) where 29% and 24% of respondents respectively reported experiencing or witnessing discriminatory behaviour.

Where the BVA's surveys examined the profession as a whole, we were interested in the student experience. Our findings were broadly similar with 36% of respondents experiencing or witnessing discrimination, with 30% of experienced incidents taking place in small animal practice, 38% in farm animal practice and 17% in equine practice. The main perpetrators of the discrimination experienced were vets in 39% of incidents and the public in 37% of incidents (Summers et al, 2020). The patterns were similar across profession sectors. When examined by specific characteristics including age, disability status, ethnicity, gender and sexuality, the students with any specific minority characteristic was statistically significantly more likely to experience or witness discrimination against that characteristic. It is probable that students from a minority group will more vigilant to specific discriminatory behaviours or comments, but this will be having an impact on students. Meyer's concept of minority stress is where members of a minority will experience stress based on the expectation of discrimination even where none has been experienced directly (Meyer et al, 2008).

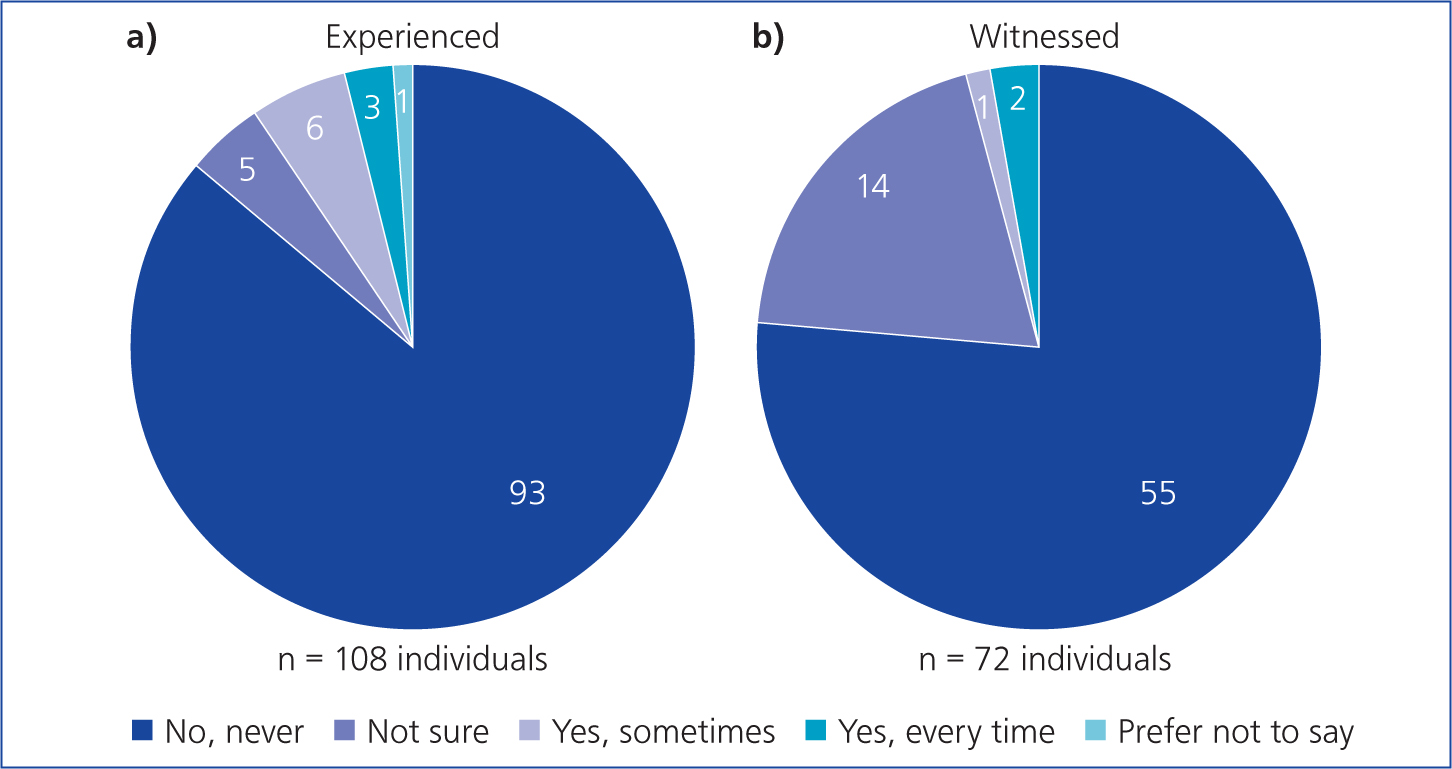

The BVA surveys identified that reporting of incidents of discrimination was low at 31% and 29% (BVA, 2019), but lowest in students at 19% (BVA, 2019). Our student survey had a much lower value at 8% (Figure 1). The most common reasons for not reporting were thinking nothing would be done, not knowing how to report, or fear of consequences of reporting.

Student opinions regarding discrimination were also examined in the survey. Themes from this component of the research were that students from a minority group were more likely to agree that discrimination against their group was an issue. For example, LGBTQ+ students were more likely to agree that being ‘out’ made them more vulnerable. Interesting points to come from this part of the research were that a significantly larger proportion of BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) students disagreed that racial diversity needed to be improved, male students tended to take a different view on most subjects than female students, and the majority of students were neutral on how veterinary professional bodies were tackling discrimination.

The research stimulated discussion in the form of a discrimination and client communications workshop. How can veterinary workplaces better protect and support students seeing practice and their staff from discriminatory behaviour and comments? Is the problem of discrimination experienced by students and other members of veterinary workplaces a problem with malicious intent or one of ignorance? Our research identified that most incidents were flippant comments or jokes often with little thought behind them. This is not to belittle any effect those types of comments have on people, but in fact to make the point that intent does not equal impact. A comment made, may not be intended to cause harm, yet still has a negative impact on those that it is targeted toward or those that witness it (Tannenbaum, 2013). However, intent can play a role in potential solutions. Where there is no malicious intent, education and information is the best approach. Most perpetrators are unaware of the harm they have caused. How do we educate? This is where Daniella Dos Santos of the BVA advised that professional bodies and interest groups need to be working together on solutions to avoid duplication of efforts and potential diluting of the important message. The professional bodies have the resources and reach, while the interest groups have the expertise. Furthermore, the problem of discrimination, while neglected, is not unique to the veterinary profession.

There are numerous resources and toolkits produced by different organisations that we can use or learn from. For example, the NHS produced posters on microaggressions toward different minority groups (NHS, 2019). Microaggressions are small comments or actions that are discriminatory and do harm to people often borne out of societal misconceptions and biases conscious or unconscious. For example, ‘did you not want any children?’ said to women, or ‘you are too pretty to be a lesbian’, or ‘you speak English so well!’. Comments like these examples, and our research identified many, may even be intended to be complimentary but do not have that impact. By making our colleagues aware, we can start to limit the well-intentioned but ignorant and ultimately harmful comments. Posters in practice waiting rooms can help educate clients and reduce the quantity of ill-judged comments from members of the public. Colleagues can be educated in more depth through webinars, online courses, and workshops as CPD. In fact, training materials is something some of the interest groups are working on right now.

Education, training and posters only go so far. Feedback from examples of educational programmes and some comments in our research show that there are still those that deny discrimination and the effects it has on people is real. How often is someone told to not be so sensitive, or that other people have it worse, or it was only a joke? There are sadly an awful lot of our colleagues and members of the public who are not receptive to education. Conferences such as Courageous Conversations attract those for whom discrimination is an important issue. Therefore, we reach the ‘converted’, so-to-speak. How do we reach the rest? The BVA Discrimination Survey found that 60% of self-employed/owner/partner vets were either not very concerned (44%) or not at all concerned (16%) by levels of discrimination in the profession (BVA, 2019). Mandisa Greene, the new RCVS president, had kindly joined the conference by phone to listen and contribute to our discussions. The RCVS has the power to enforce the legal requirements of CPD in terms of hours, but cannot mandate where those hours are spent, so a mandatory discrimination awareness training is not an option for us. Also, while not part of the practice standards scheme, RCVS do encourage that workplaces do undertake training.

Other solutions?

Students need to feel supported by their universities while seeing practice. They need to be confident that placements publicised on university EMS databases are safe. Students want to know that if they are not comfortable or in danger at a placement, that they can leave without difficulty and challenge from university placement teams. Students stated in the workshop that they would be more likely to report concerns to their universities if they felt listened to and that action would be taken. It is disheartening to not be believed and then see a hostile placement remain on a database. Transparent policies and actions on those policies are vital to encourage students to report. Furthermore, the individuals picking up reports or interacting with students need to understand the impact microaggressions and other discriminatory behaviours and comments have on people so that incidents are not dismissed as trivial. Small incidents have a cumulative effect.

Finally, the problem of discrimination from within the veterinary profession and from the clients we see seems like an insurmountably large problem. But, while it seems like we are trying to turn an oil tanker, oil tankers can be steered and will eventually reach port. As individuals we can make sure we keep up with our own education, stretch our comfort zone by just 2% each time, try to reach just 2% more people each time, and we can eventually tackle the problem. We must also be active bystanders. When we witness microaggressions or other discriminatory behaviours, challenge those behaviours and let our colleagues and clients know that discrimination is not welcome in the veterinary profession.