Hip dysplasia is a common orthopaedic condition seen in dogs and is characterised by joint laxity and incongruency between the femoral head and the acetabulum (Smith et al, 2017). This results in inflammation, microfractures, secondary osteoarthritis and clinical signs of pain and lameness. Efforts to reduce the prevalence of this condition through breeding schemes have been implemented; however, because of the multifactorial nature of hip dysplasia, with a combination of environmental factors and a complex mode of inheritance, the prevalence within the canine population remains high (Smith et al, 2017). Therefore, knowledge of management options for this condition is important for the general practitioner.

Diagnosis

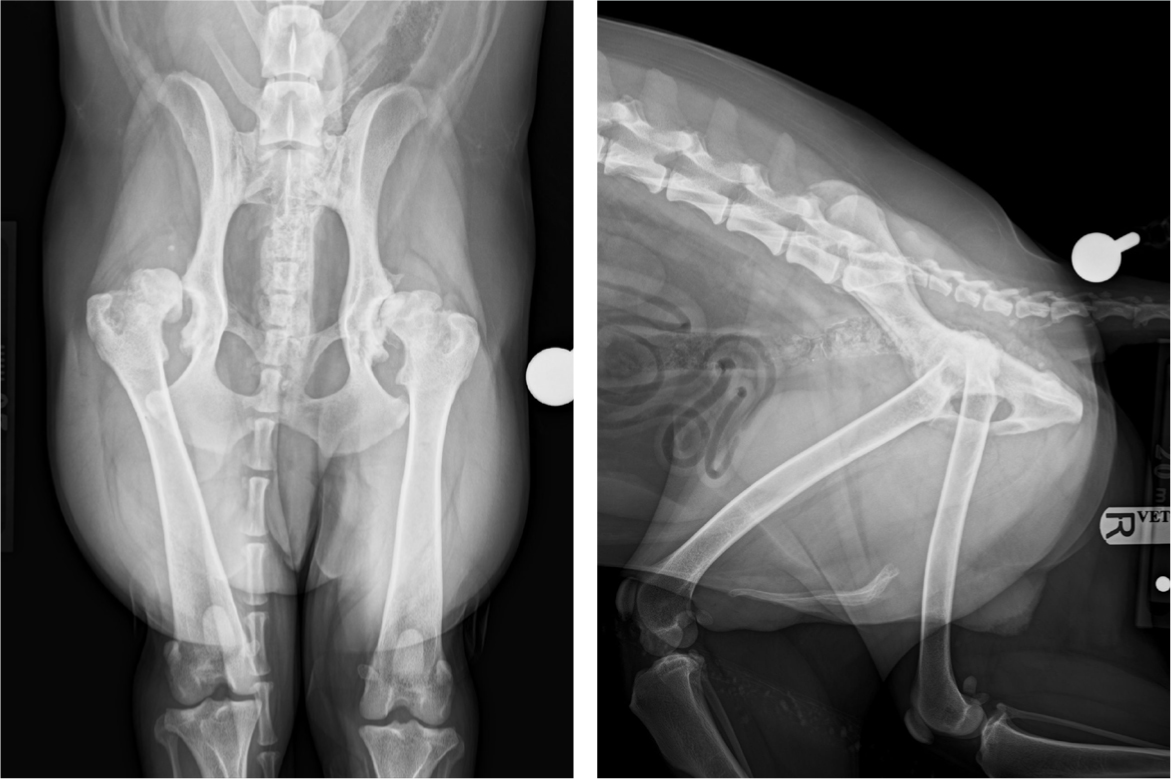

A diagnosis of hip dysplasia can be made from a set of standard orthogonal hip radiographs (Figure 1). However, it is important to correlate imaging findings with the clinical signs demonstrated by the patient when determining the need for, and most appropriate course of, treatment. The prevalence of hip dysplasia is high and will often be diagnosed alongside other orthopaedic conditions that may be more relevant clinically, such as cranial cruciate ligament rupture (Powers et al, 2005). Although radiography is not 100% accurate for diagnosing hip dysplasia and false negatives can occur, this is less likely to occur in clinical cases. Stressed radiographic views can be used to further assess hip laxity, such as the PennHip method to obtain a distraction index (Smith et al, 1990). The distraction index remains constant from 16 weeks of age and appears to be a reliable indicator of the risk of developing hip dysplasia later in life (Smith, 1997; Smith et al, 1998). A lower distraction index correlates with reduced hip laxity, and values <0.3 have been associated with a reduced risk of developing hip dysplasia (Smith, 1997; Smith et al, 1998). Radiation safety rules in the UK do not allow for human restraint while performing radiography as part of a screening process but can be used where the clinical situation justifies it. As such, these views are not commonly performed in the UK (Ginja et al, 2010).

The Ortolani test is commonly used to assess coxofemoral laxity in dogs over 4 months of age (Chalman and Butler, 1985; Ginja et al, 2010). A positive Ortolani test is consistent with hip laxity, but a negative result does not always indicate a congruent joint (Ginja et al, 2009a; Ginja et al, 2009b). Secondary remodelling of the coxofemoral joint and thickening of the joint capsule can prevent the detectable clunk (Ginja et al, 2009b; Ginja et al, 2010).

Two populations of dogs tend to present with clinical signs attributable to hip dysplasia. Young dogs, between 5 months and 1 year of age, may present with variable degrees of hindlimb lameness and exercise intolerance as a result of joint laxity and subsequent subluxation of the femoral head and synovitis (Gemmill and Oxley, 2018). As a result of the abnormal loading of the coxofemoral joint, joint capsule thickening, osteophyte formation and joint remodelling occur to reduce instability. This typically coincides with a decrease in joint pain and improvement in clinical signs by the age of 12–18 months (Brown, 2016; Gemmill and Oxley, 2018). Older dogs may present with clinical signs of hip pain and stiffness, which are generally attributable to these secondary osteoarthritic changes. Treatment options depend on multiple factors, such as age at presentation, severity of clinical signs, degree of joint laxity and response to initial conservative management.

Conservative management

Conservative management combines analgesia, exercise modification and weight control (Smith et al, 2017; Gemmill and Oxley, 2018). Smith et al (2006) demonstrated the significant impact that diet control and weight play in the development of hip osteoarthritis; therefore, owners should be counselled on these findings in any young dog, irrespective of whether hip dysplasia has been diagnosed. In patients with an underlying orthopaedic disease such as hip dysplasia, even in the absence of clinical signs, more emphasis should be placed on the role of weight in conservative management. An in-depth review of all aspects of conservative management is beyond the scope of this article – however, the efficacy of conservative management should not be underestimated.

All patients with clinical signs should undergo a period of conservative management before surgery is performed. If clinical signs improve, this may be all that is required for treatment of the case. Surgical indications include:

- Increased severity of clinical signs

- Increased frequency of flare-ups

- Continued limited mobility that compromises quality of life.

The evidence suggests that many cases of canine hip dysplasia will respond to conservative management. Studies have demonstrated no significant difference between dogs managed conservatively and those treated with prophylactic procedures when assessed by gait analysis (Planté et al, 1997a; Dueland et al, 2001). Radiographic changes will ultimately progress as the body continues to try to stabilise the lax hip joint; however, these changes do not always correlate with clinical signs. Barr et al (1987) reported that 89% of conservatively managed patients had signs of increased periarticular bone formation at long-term follow up compared to at the time of diagnosis. However, 76% of these dogs had a normal gait or only slight or intermittent gait abnormalities at long-term follow up.

Conservative management requires extended owner compliance in order to achieve good outcomes, including continued assessment of the need for analgesia and acceptance that some patients will require life-long medication. Farrell et al (2007) reported that at an average follow up time of 4.8 years, 92% of dogs examined were lame on a pelvic limb, but only 33% of these patients were being treated with analgesia. This highlights the importance of owner education of clinical signs and regular monitoring of these patients. Some dogs will not respond to conservative management, and therefore surgical management is warranted to alleviate pain.

Prophylactic procedures

Prophylactic procedures can be considered in immature dogs with a positive Ortolani test and no evidence of secondary osteoarthritis or degenerative joint disease, with the aim to prevent the progression of clinical hip dysplasia and the secondary changes that are a sequela to joint laxity (Smith et al, 2017).

Juvenile pubic symphysiodesis

Juvenile pubic symphysiodesis is a procedure that involves electrocauterisation of the pubic symphysis to induce thermal necrosis of the germinal cells and results in premature closure of the growth plate (Swainson et al, 2000). The ventromedial aspect of the pelvis ceases to grow, while the dorsolateral aspect continues to develop normally, resulting in the acetabulum rotating ventrolaterally, increasing femoral head coverage (Patricelli et al, 2002). The effect of juvenile pubic symphysiodesis has been evaluated by several studies and has been shown to improve joint congruity and reduce progression of secondary osteoarthritis (Dueland et al, 2001; Linn, 2017). However, case selection has been shown to be highly important in order to optimise outcomes. As an open pubic growth plate is required to perform this procedure, candidate suitability is limited to very young patients with better outcomes seen the younger the surgery is performed, in particular less than 4 months old (Dueland et al, 2001; Patricelli et al, 2002). Studies have demonstrated that juvenile pubic symphysiodesis is ineffective at correcting severe hip dysplasia, and better outcomes are seen with cases with a distraction index of <0.7 (Vezzoni et al, 2008; Linn, 2017). Therefore, dogs with severe hip dysplasia are not candidates for juvenile pubic symphysiodesis. Most patients that would be ideal candidates for juvenile pubic symphysiodesis are likely to be asymptomatic at the time that surgery should be performed, and hip dysplasia would only be detected by screening through hip laxity tests performed under sedation, such as the Ortolani test, alongside radiography (Dueland et al, 2001). This is ethically questionable, and many candidates identified on screening with mild hip dysplasia may never demonstrate significant clinical signs.

Juvenile pubic symphysiodesis may be discussed with owners as an option for very young patients, ideally less than 4 months old, with evidence of hip laxity as identified by a positive Ortolani test and radiography, with or without distracted views performed. However, it should be noted that if a high degree of hip laxity is detected, then juvenile pubic symphysiodesis is unlikely to result in a successful outcome and other management options should be considered.

Pelvic osteotomies

Triple pelvic and double pelvic osteotomies have been described as prophylactic procedures to manage hip dysplasia (Slocum and Slocum, 1992; Vezzoni et al, 2010; Lopes et al, 2018). A triple pelvic osteotomy includes osteotomies of the pubis, the ischium and the ilium (Slocum and Slocum, 1992). Studies have demonstrated that triple pelvic osteotomies can improve function in young patients with hip dysplasia (Planté et al, 1997b; Manley et al, 2007). However, other reports have failed to demonstrate elimination of hip laxity postoperatively or a decrease in the progression of secondary osteoarthritis (Johnson et al, 1998; Manley et al, 2007; Lopes, 2018). Furthermore, notable complication rates have been reported with the triple pelvic osteotomy procedure since it was first described, in the range of 29–70% (Koch et al, 1993; Remedios and Fries, 1993; Planté et al, 1997a; Doornink et al, 2006). Minor modifications were made to the technique, including the use of new bone plates, in an attempt to reduce this high complication rate. The double pelvic osteotomy was then described, which does not include the osteotomy of the ischium (Haudiquet and Guillon, 2008; Vezzoni et al, 2010). It has been proposed that the lower complication rates seen with the few initial reports of the double pelvic osteotomy are because of the exclusion of the ischiatic osteotomy and increased stability of the pelvis (Vezzoni et al, 2010). Small case series of both double and triple pelvic osteotomies have demonstrated lower complication rates, which may be in part as a result of improved surgeon experience with the technique, alongside advances in implants and surgical technique (Rose et al, 2012a; 2012b; Guevara and Franklin, 2017). Similarly to the juvenile pubic symphysiodesis surgery, those with moderate to severe hip displasia are very unlikely to achieve suitable oucomes following triple or double pelvic osteotomy surgeries.

Ultimately, many dogs present with clinical signs of hip dysplasia at an older age, when these prophylactic procedures can no longer be performed. In patients that present with clinical signs of hip dysplasia at a young age, careful assessment needs to be performed before recommending prophylactic surgical procedures as the degree of hip laxity may not be correctable by these procedures and secondary osteoarthritis may not be halted. Therefore, other management options are required for these cases.

Salvage procedures

Femoral head and neck excision

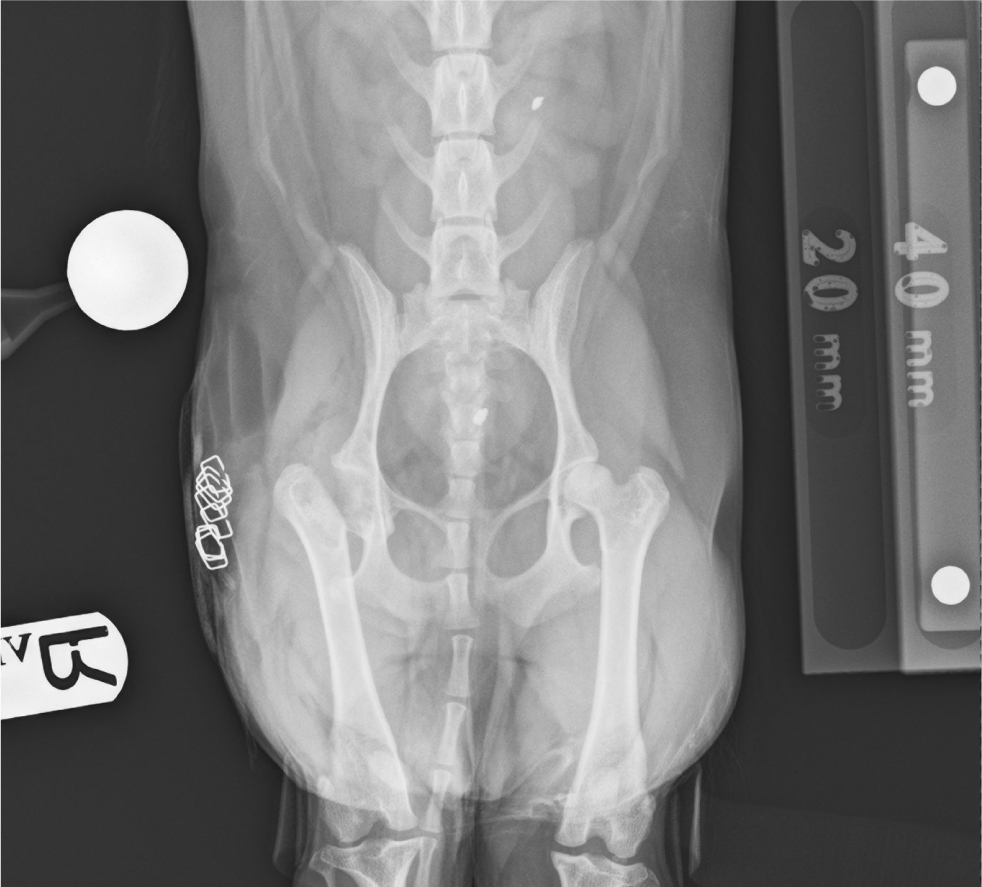

Femoral head and neck excision has been recommended as a salvage procedure to treat canine hip dysplasia in cases that have not responded to conservative or other surgical managements (Figure 2). The procedure involves ostectomy of the femoral head and neck and aims to alleviate the pain associated with ‘bone-on-bone’ contact between the degenerative femoral head and acetabulum (Smith et al, 2017). Femoral head and neck excision is a relatively simple procedure that has been shown to result in satisfactory outcomes if post-operative rehabilitation is performed properly (Berzon et al, 1980; Rawson et al, 2005; Fattahian et al, 2012; Arun and Yeshwanthkumar, 2016). However, early postoperative mobilisation is important in improving the chance of a successful outcome. Planté et al (1997b) demonstrated that dogs who underwent femoral head and neck excision showed increased activity levels and lower pain scores following surgery than dogs who were managed conservatively for hip dysplasia. Complications following femoral head and neck excision can include shortening of the limb, sciatic nerve damage or entrapment, patellar luxation, muscle atrophy and decreased range of motion of the hip, alongside continued pain (Harper, 2017). As a fibrous joint forms, early post-operative limb use is essential to maintain adequate range of motion (Harper, 2017). Therefore, physiotherapy should be initiated before surgery and continued post-operatively to improve muscle mass and encourage early post-operative mobilisation. Femoral head and neck excision is often chosen by clients because of financial constraints or concerns regarding complications following total hip replacement, or as a response to a failed total hip replacement.

Total hip replacement

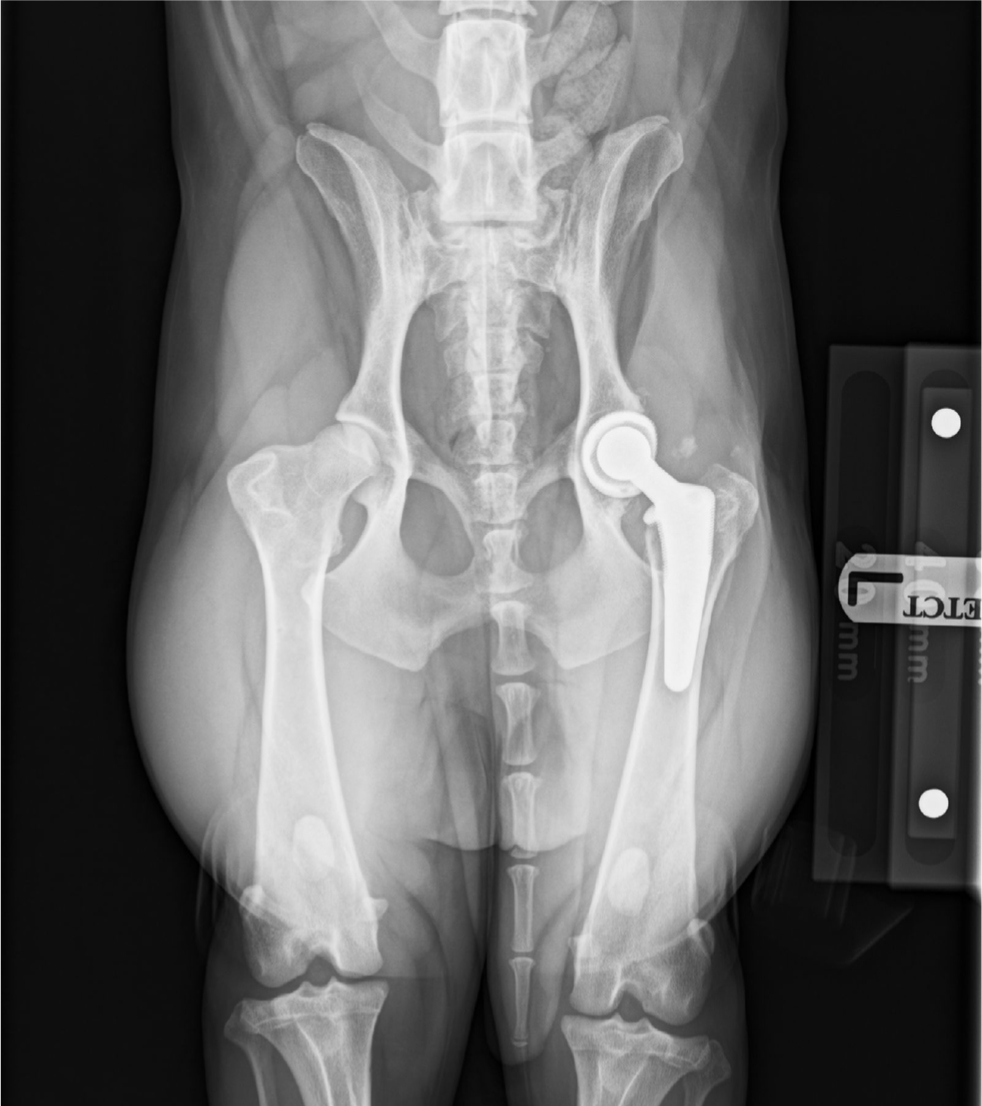

Total hip replacement is currently considered the treatment of choice for patients with hip dysplasia who present at an age older than that at which prophylactic procedures can be considered, have secondary osteoarthritic changes and/or a greater degree of hip laxity, who are refractory to conservative management (Figure 3). Since the first veterinary total hip replacement implants were introduced in 1974, much research has been performed to develop newer implants, with lower complication rates and improved outcomes (Hoefle, 1974). Total hip replacement systems are now available for a wide range of canine and feline patients, weighing between 2 kg and 80 kg (Liska, 2010; Gemmill et al, 2011; Ireifej et al, 2012; Marino et al, 2012; Schiller, 2017; Allaith et al, 2023). Total hip replacement systems are broadly categorised into cemented and cementless systems, with surgeon preference and patient factors determining the system chosen. Hybrid systems are also now available, which allow surgeons to use a cemented or cementless acetabular component with a cemented or cementless femoral stem. Hybrid systems produce similar outcomes and complication rates as those reported for complete cemented and cementless systems (Gemmil et al, 2011; Allaith et al, 2023).

Regardless of the system chosen, the outcomes following total hip replacement have been reported as excellent when performed by surgeons with sigificant experience of total hip replacements. The largest case series to date collates data from 2375 total hip replacements recorded in the British Veterinary Orthopaedic Association Canine Hip Registry, alongside owner reported outcomes (Allaith et al, 2023). This study reported a complication rate of 8.5%, with the most frequent complications including luxation, fracture and aseptic implant loosening. Despite the occurrence of these major complications, 88% of owners reported the outcome following surgery as very good or good. Post-operative Liverpool osteoarthritis in dogs scores were much improved compared to pre-operative values (11 compared to 21). Other smaller studies have demonstrated similar outcomes following total hip replacement (Bergh et al, 2006; Lascelles et al, 2010; Liska, 2010; Gemmill et al, 2011; Khanuja et al, 2011; Forster et al, 2012; Ireifej et al, 2012; Marino et al, 2012; Fitzpatrick et al, 2014; Henderson et al, 2017; Kwok and Wendelburg, 2023).

The literature demonstrates that even in the face of major surgical complications, the outcomes reported following revision surgery are good–excellent. Liska (2004) documented that owners reported normal limb function in 75% of cases after revision surgery to treat a femoral fracture following total hip replacement, with the remaining 25% of owners reporting ‘good’ limb function. Other studies have reported similar rates of success following treatment of major surgical complications (Nelson et al, 2007; Allaith et al, 2023; Kwok and Wendelburg, 2023). Therefore, the evidence suggests that the occurrence of a major complication in the short-term does not adversely affect long-term outcomes in the majority of patients treated with total hip replacement.

Conclusions

There are multiple options for the management of canine hip dysplasia and the most appropriate option varies from case to case. Prophylactic surgical management is often not feasible, as candidates seldom present without the presence of secondary osteoarthritic changes and at the ideal young age that surgery should be performed. Severe cases of hip dysplasia, with a greater degree of hip laxity, may be more likely to present at a younger age, however prophylactic procedures are ineffective at correcting severe hip incongruency. Conservative management should be initiated beforeperforming any surgical procedure. All surgical procedures are not without risk and therefore the definitive need for surgery should be established beforehand. In patients who do not respond to conservative management, the evidence shows that total hip replacement results in consistently good and predictable outcomes, with low complication rates. Should complications occur, a high proportion of cases still achieve a good outcome following treatment.

KEY POINTS

- Hip dysplasia is a common orthopaedic condition seen in dogs.

- Prophylactic surgical procedures can be considered for immature patients with mild hip dysplasia and lack of secondary osteoarthritic changes. However, the definitive efficacy of these procedures has yet to be consistently proven.

- Femoral head and neck excision can be considered as a salvage procedure for patients with severe pain related to hip dysplasia.

- Total hip replacements result in the best outcome of the options available for management of hip dysplasia, with a high proportion of dogs returning to full function of the limb, and low complication rates, with good outcomes still achieved even if complications occur.