Vaccines and preventative medicine are as important today as they have ever been. While the world comes to terms with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, we are living in the reality of human vaccination being one of the most important approaches we can take to reduce disease transmission and infection, both nationally and globally. Like other preventative practices, the same principle applies to diseases of veterinary significance, such as rabies (Sanchez-Soriano et al, 2020). The incidence of what is being termed ‘vaccine hesitancy’, or the delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite the availability of vaccine services (WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (on Immunisation) 2014), has begun to appear in veterinary reports (McGowan, 2019; Mattson, 2020; Kogan et al, 2021). It is a fundamental part of evidence-based veterinary practice that an understanding of how stakeholders perceive their role within, and beliefs about, animal health is key for successful knowledge exchange interactions. For evidence-based veterinary research to be successful, all key stakeholders should be involved in the research creation process to ensure an outcome that is applicable to, and useable by as many professionals as possible. These practice-based and research perspectives are key in areas such as preventative medicine, where communication about the risks and benefits is vital for successful implementation. As the UK veterinary industry re-evaluates how it approaches the day to day running of veterinary practice in the aftermath of the introduction of COVID-19 in 2020, having a good grasp of stakeholders' perspectives is more important than it has ever been, particularly in terms of preventative healthcare.

The Centre for Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine in the School of Veterinary Medicine and Science at the University of Nottingham was officially established in 2010, with the aim of assisting veterinary professionals to use an evidence-based approach to clinical decision-making. This includes working closely with veterinary stakeholders to identify research questions of importance and, where possible, answering them with robust methods or ensuring that the results of research are disseminated and integrated into clinical decision-making. Preventative healthcare has been one of the main areas of focus across many species. For further information about the Centre for Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine, visit the website (www.nottingham.ac.uk/cevm).

In this article, what the Centre for Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine has learned from 10 years of research focused on preventative healthcare in small animal practice is highlighted

Methods and findings

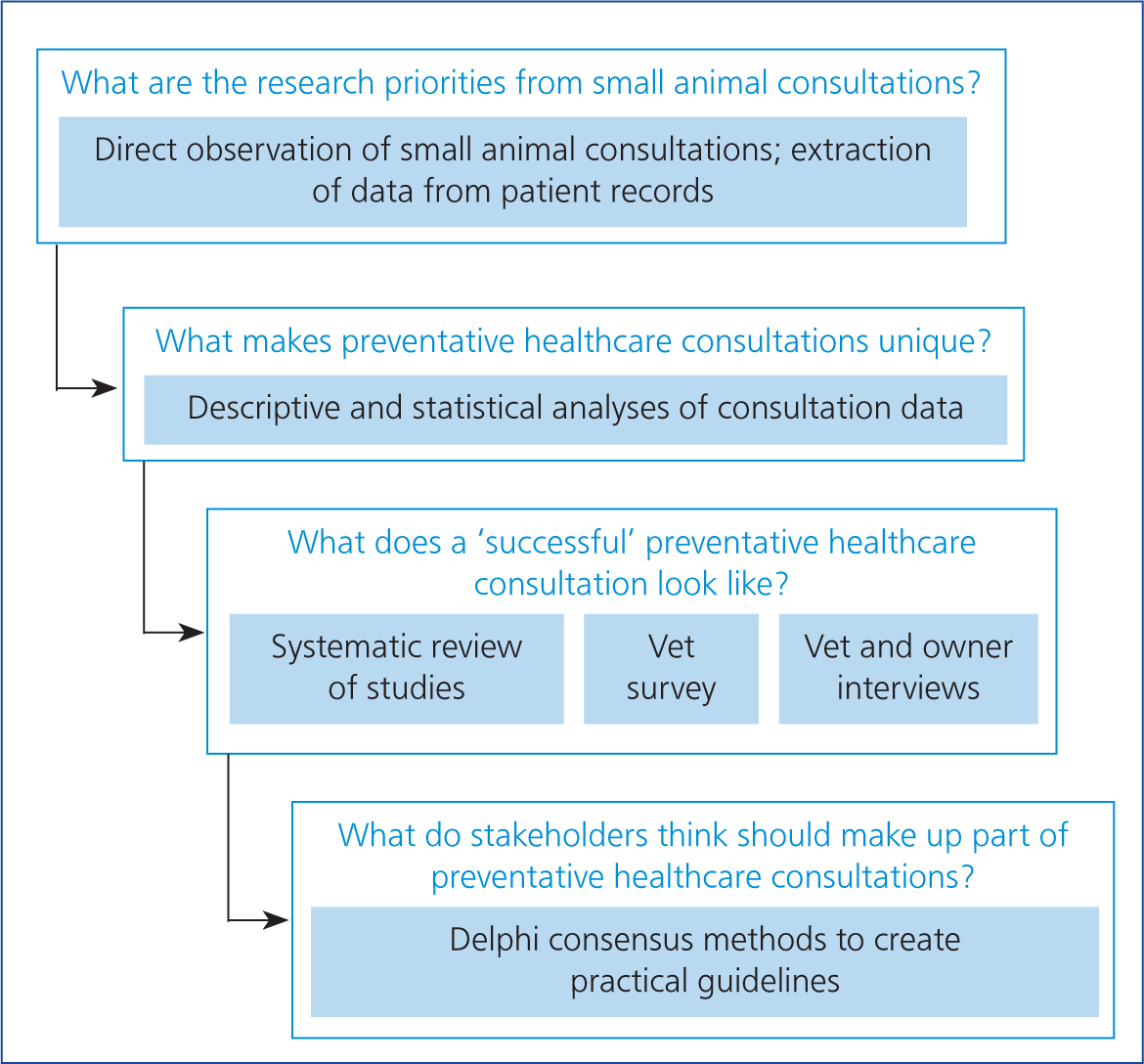

Researchers within the Centre for Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine initially used broad-based approaches to identify the research priority areas for the veterinary profession. This involved direct observation of small animal consultations to document interactions, in combination with investigation of data extracted from practice management software systems. The data were analysed descriptively and statistically to highlight novel and pertinent findings about these interactions and determine areas for further investigation.

Preventative medicine consultations were recognised as a research priority. Once questions of importance were identified, further detailed investigations were undertaken with a range of stakeholders (including vets and owners) involving systematic reviews, surveys and interviews, to identify what a ‘successful’ preventative medicine consultation looked like. This was followed by a consensus-based study involving pet owners and vets, prioritising the findings gathered from the previous years of research and developing a guideline for what should be considered in a preventative medicine consultation. An overview of this process can be seen in Figure 1.

Research priorities: what makes preventative healthcare consultations unique?

Gathering data on interactions during small animal consultations revealed that for over one third (35%) of small animal consultations, preventative healthcare was the primary reason for presentation. These consultations were decidedly complex, a fact not previously described. Up to eight different problems were discussed in some consultations, and interestingly, more problems were discussed during consultations where the patient had been presented for a preventative healthcare problem, than during consultations for a specific health problem (Robinson et al, 2015).

Comparative work with health problem consultations identified that preventative healthcare consultations involved a younger population of patients, and were more likely to involve (Robinson et al, 2016):

- More than one animal

- A full clinical examination

- An animal being weighed

- Discussions that focused on obesity, dental disease and behavioural problems

- Significantly more problems being discussed and acted upon

- Of the total problems discussed, 40% were raised by a veterinary surgeon (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of preventative healthcare consultations versus consultations focused on a specific health problem

| Type of consultation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preventative healthcare | Health problem | ||||

| Characteristic | Categories | n | % | n | % |

| Multiple animals | Yes | 116 | 16.8 | 32 | 2.9 |

| No | 574 | 83.2 | 1085 | 97.1 | |

| Total | 690 | 100.0 | 1117 | 100.0 | |

| Type of clinical examination | None | 38 | 5.5 | 108 | 9.8 |

| Focused | 49 | 7.1 | 504 | 45.6 | |

| Full | 603 | 87.4 | 494 | 44.7 | |

| Total | 690 | 100.0 | 1106 | 100.0 | |

| Weighing | No | 282 | 40.9 | 655 | 59.2 |

| Yes | 408 | 59.1 | 451 | 40.8 | |

| Total | 690 | 100.0 | 1106 | 100.0 | |

The findings suggest preventative healthcare consultations are far from being ‘just a vaccine’ or the ‘quick and easy’ consultations they are often perceived to be. However, data from this research demonstrates that these consultations are not significantly shorter than health problem-based consultations (Robinson et al, 2014), in agreement with previous studies (Shaw et al, 2008; Everitt et al, 2013). In some cases, no action other than ‘watchful waiting’ was taken for these additional health problems, however for most (58%), at least one action (such as diagnostics, therapeutics or management advice) was taken, highlighting the complex decision-making for multiple problems which takes place during preventative healthcare consultations.

What does a ‘successful’ preventative healthcare consultation look like?

Systematic review

A systematic review was undertaken with the aim of identifying any previously validated (or rigorously tested) ‘measures of success’ in preventative healthcare consultations (Robinson et al, 2018). Seven published research papers describing various aspects of preventative healthcare consultations, including content and communication, were identified, with only one paper measuring the ‘success’ of preventative healthcare consultations by examining unvalidated veterinary surgeon satisfaction with the consultation (Shaw et al, 2012).

Veterinary survey

During the survey, veterinary surgeons were asked to think specifically what they would do and discuss during a typical adult booster vaccination consultation (Robinson et al, 2019). The findings suggest that there are certain aspects of the clinical examination that most veterinary surgeons would perform for almost every patient (such as chest auscultation, abdominal palpation and visual examination of the extremities). However, there were other aspects of the clinical examination and discussion topics that were conducted in a more variable way (for example, checking pulses, otoscopic examinations and discussions around neutering).

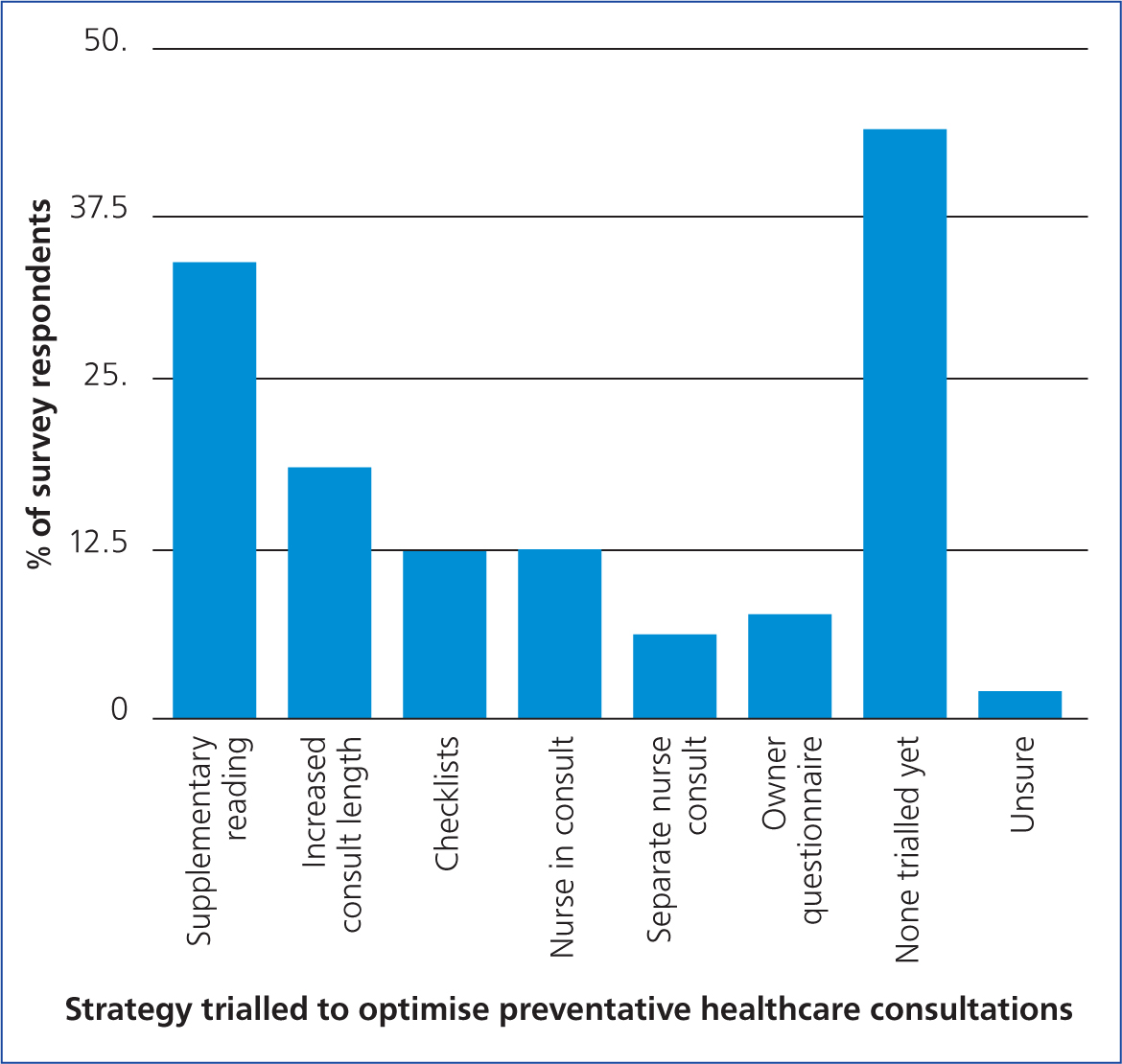

Over half (54%) of veterinary surgeons responding to the survey had tried strategies to optimise preventative healthcare consultations (including providing owner leaflets, time allowance for preventative healthcare consultations and completing checklists) (Figure 2). Some were considered more easily implemented than others, and the same was identified for the effectiveness of measures. Many veterinary surgeons reported their practice ran a pet health plan or similar, though there was variation in how these were perceived by participants, with some participants unclear as to what the plan included.

In-depth interviews

During in-depth telephone interviews with veterinary surgeons and owners, expectations and experiences of the consultation appeared to vary widely between different individuals (Belshaw et al, 2018a). Some veterinary surgeons reported that they found preventative healthcare consultations to be highly rewarding, and an important part of their caseload, while others reported that they did not find them as interesting or as challenging as other consultations. This was also reflected by pet owners, most of whom welcomed and expected more than just a vaccination being given and felt dissatisfied when these expectations were not met.

Several motivators and barriers to the use of preventative medicines were also identified during these interviews (Belshaw et al, 2018b). The importance of a trusting relationship between the veterinary surgeon and pet owner was often highlighted, but not exclusively, as some owners sought information from breeders and online resources. Some owners highlighted concerns about adverse events and whether preventative medicines were necessary. The latter point was mirrored by the veterinary surgeons, who acknowledged the limited understanding some owners appeared to have about the importance of using preventative medicines. Veterinary surgeons expressed concern about how some owners would perceive the potential conflict between vets advising on, and profiting from, the use of products such as vaccines.

Time was another important factor highlighted, with the perception of preventative healthcare consultations as ‘quick and easy’ and an opportunity to ‘catch-up’ when running behind persisting for some veterinary surgeons (Belshaw et al, 2018c). Both veterinary surgeons and pet owners reported feeling rushed or having to rush, which often led to vets reporting an inability to raise all discussion points they wanted to, and pet owners missing an opportunity to discuss an aspect of their animal's health.

The role of veterinary nurses and receptionists in preventative healthcare was also highlighted (Belshaw et al, 2018d), even though these practice team members were not interviewed. These members of staff were often involved in discussions outside of the consultation, particularly in practices using pet health plans. Pet owners were often uncertain as to the exact role of the member of staff they were speaking to, as well as the kind of help and advice available from this member of staff. These members of staff appear to have an important role in client education and rapport building, as well as developing client trust, so additional research is needed to expand upon this.

Development of evidence-based guidelines for preventative healthcare consultations

Building on the findings above, researchers at the CEVM used a consensus methodology to engage all key stakeholders in the development of guidelines in a transparent and repeatable manner. These methods result in the production of guidance which is more useful in a practice setting. To the authors' knowledge, these are the first veterinary guidelines to involve owners in their development.

Initially, 18 key statements were identified from the survey and interview data by the Centre for Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine team. A panel of veterinary surgeons and pet owners with extensive experience of preventative healthcare consultations were then recruited and asked to complete three rounds of anonymous online questionnaires. This involved asking whether they believed the statements should be considered an essential part of the guidelines, with a consensus being deemed to be reached for a recommendation when at least 80% of respondents agreed (or disagreed) with the statement.

At the end of the three surveys, 13 recommendations had been agreed upon, with no consensus having been reached for the remaining five statements (Belshaw et al, 2019). An abridged version of the recommendations as agreed by the panel can be seen in Box 1.

Box 1.Evidence-based guidelines for preventative healthcare consultations in small animal practice.The practice team should agree beforehand on:

- The purpose and content of their preventative healthcare consultations to improve consistency

- The role of each member of the team (including vets, nurses and receptionists) in preventative healthcare consultations

- How the cost details of preventative healthcare will be communicated to owners

- How potential risks associated with preventative medicines will be communicated to owners

- How to make clear to owners the benefits of preventative healthcare and medicines to individual animals, pet populations and public health.

Before each preventative healthcare consultation:

- It should be explained to owners what might happen and which topics may be discussed

- Owners should be encouraged to consider questions they have about their pet's health or preventative healthcare

- Each preventative healthcare consultation should be tailored timewise to the individual patient, and adjusted for patient age, species and known pre-existing conditions.

During each preventative healthcare consultation:

- Owners should be encouraged to ask any questions they have about their pet's health or preventative healthcare

- A full clinical examination should be undertaken by a veterinary surgeon or veterinary nurse

- Patients should be weighed and have their body condition score assessed using a scale pre-agreed by the practice team

- Owners should be made aware of both normal and abnormal findings from a clinical examination

- It must be ensured that owners understand the rationale behind any recommendations made and that the alternatives are discussed where appropriate.

How should these guidelines be used?

The way these guidelines could be integrated into veterinary practice is important to consider. Guidelines are not rules to be strictly followed and some recommendations may not be feasible or effective for every practice setting. They should be seen as a starting point for open and non-judgmental group discussions with all practice members regarding what is currently being done by everyone, and what could and should be done as part of these consultations. As part of these deliberations, how to determine and monitor successful implementation of the guidelines will be an important consideration.

Conclusions

In conclusion, 10 years of research work in this area has shown that preventative healthcare consultations are highly complex and represent an important opportunity to address a variety of pet health issues with animal owners, which may not be raised during other types of interactions. It is during these conversations that complex issues, such as vaccine hesitancy, can be identified and explored fully to ensure that informed decisions are being collectively made by the veterinary and owner team for the animal.

It is the hope of the Centre for Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine team that the guidance developed provides a useful and practical framework for veterinary practices considering how they can maximise the benefits of these consultations. The five key findings from this body of work are:

- Preventative healthcare consultations are common, complex and time-pressured

- Owner expectations and experiences of preventative healthcare consultations varies widely. Finding out what your clients expect from a preventative healthcare consultation may be useful

- Veterinary nurses and receptionists play an important role in preventative healthcare, but these roles may need clarifying both amongst the practice staff and to your clients

- There are practical, evidence-based guidelines that have been developed to optimize preventative healthcare consultations.

- The guidelines are a series of suggestions rather than rules, which should be examined to see which may work best in your practice, and the effects of making any changes should be monitored.

KEY POINTS

- Preventative healthcare consultations small animal practice are common, complex, and typically under time pressure. It is worth investigating owner expectations around preventative healthcare consultations as they can vary depending on several factors, including past experiences.

- Veterinary nurses and receptionists appear to play a significant role in preventative healthcare. Clarity is needed as to the responsibilities of these team members, as well as vets, for both practice staff and clients

- Practical, evidence-based guidance about preventative healthcare consultations has been developed by the Centre for Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine from stakeholder-informed research. This is a series of points that practices could consider when looking to optimise preventative healthcare consultations.