Toxocara is a truly ubiquitous genus of roundworms. The feline ascarid, Toxocara cati, is often considered as one of the most prevalent helminth parasites of Felis catus, the domestic cat. In addition, toxocarosis is increasingly recognised as one of the most common zoonotic parasitic infections worldwide, even in highly developed countries (Ma et al, 2020). However, much remains to be revealed on the contribution of T. cati with regards to the public health issue of toxocarosis. A better understanding of the extent of the problem, the biology and transmission routes of the parasite, epidemiology in cats, species-level diagnostic strategies in affected persons, and improving awareness among both clinicians and cat owners are pivotal in the implementation of control and prevention measures. In this article, we provide an overview of the basic biology, transmission, and clinical importance of T. cati in cats, as well as what is known regarding the zoonotic potential of T. cati and associated diagnostic challenges.

Biology and lifecycle

The two ascarid species that can produce patent infections in domestic cats are Toxocara cati (Schrank, 1788) (syn. Toxocara mystax, Fusaria mystax, Ascaris felis, Ascaris cati, Belascaris mystax, and Belascaris cati), which can also infect other felids (Fisher, 2003), and Toxascaris leonina (von Linstow, 1902), which can infect dogs as well. Both species are found worldwide with T. cati being probably one of the most commonly encountered parasites in the veterinary practice (Bowman et al, 2002). However, because to date there has been only one report of infection in humans with T. leonina of questionable validity (Grinberg, 1961), this article will only focus on T. cati. The etymology of the scientific name is: Toxo = arrow + cara = head, and cati for the domestic cat.

The Toxocara spp. of felids was initially named Ascaris cati by Schrank in 1788 and was ultimately renamed Toxocara cati (Schrank, 1788). The adult is distinctive in appearance and not easily confused with other roundworms. The most salient feature is the presence of large, arrow-head shaped cervical alae (‘wings’) on the anterior end, along with the presence of three fleshy ‘lips’ found in all ascarids. Adults measure up to 10 cm long, are offwhite to pinkish in colour, and are often found in a coiled and convoluted position (Bowman, 2014).

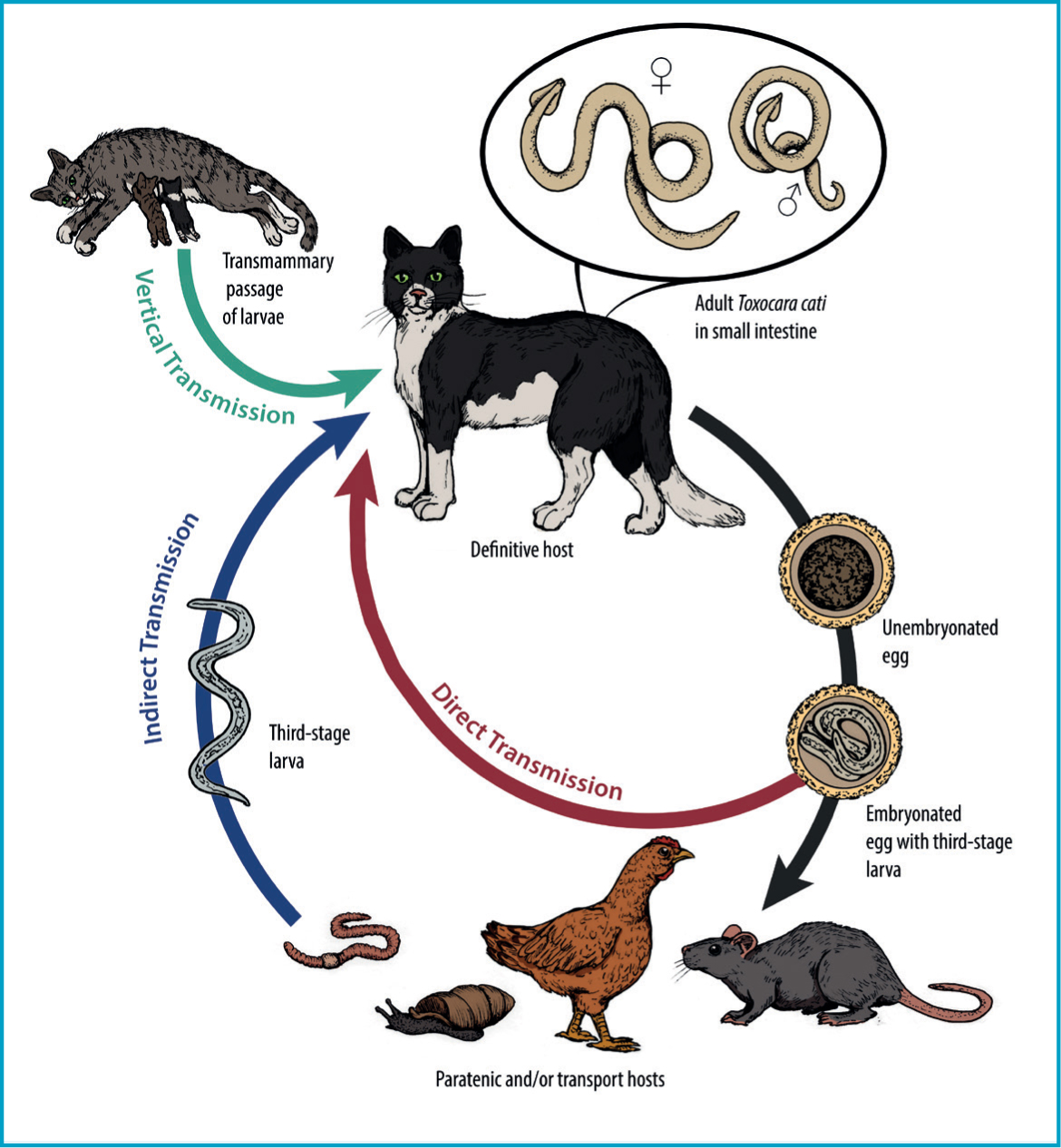

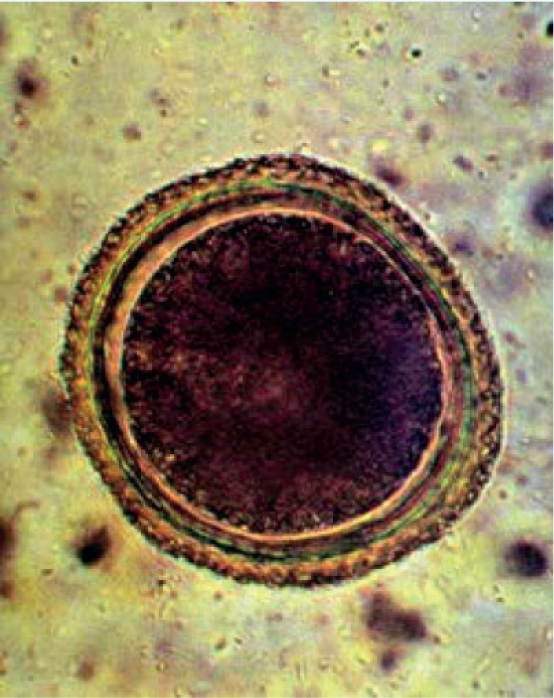

The lifecycle of this parasite can take either a direct (one host) or indirect (multiple hosts) route (Figure 1). The adult round-worms dwell in the lumen of the small intestine, wherein the female produces eggs (Figure 2) that are passed in the faeces. After a period in the environment of 2–4 weeks, the eggs reach the infectious stage. After ingestion of the embryonated eggs with the third stage larva, the larvae hatch and migrate to the liver and lungs, ascend via the trachea, are coughed up, swallowed and finally reach the small intestine. At 10 days post-infection, larvae can be recovered from both the mucosa of the stomach and muscle tissues, and fourth-stage larvae first appear after 19 days in the intestinal wall and contents. Larvae complete development to the adult stage and start producing eggs after a pre-patent period of 33–58 days (Figure 3). Typical of other ascarid infections, females are highly fecund and produce many thousands of eggs per day; average infections have egg burdens of 200–23 000 eggs per gram of faeces (Overgaauw and Nederland, 1997).

Direct ingestion of eggs is not the only route leading to patent infections in cats. Eggs containing third stage larvae are infectious to a wide variety of animals termed paratenic hosts, in which larvae hatch and undergo migration in hotissues without maturing to adult ascarids. Migration of these larvae (larva migrans) can cause clinical disease in paratenic hosts (including humans) depending on the number of larvae and the organs impacted. If cats prey on these hosts harbouring larvae in their tissues, development of the ingested larvae may proceed directly in the intestine without the hepatotracheal migration discussed above. Pre-patent periods seem to be shorter with this route of infection; if the cat feeds on a paratenic host (e.g. mice), pre-patent periods can be as short as 21 days owing to the bypass of the circuitous migration route (Overgaauw and Nederland, 1997).

Classically, the typical paratenic hosts are common prey animals such as rodents or birds, which may commonly harbour larvae in the liver, skeletal muscle, or brain tissue. Livestock and poultry may also be affected, leading to a risk of foodborne transmission to humans and other susceptible hosts. Reports of Toxocara spp. larvae, including those of T. cati, recovered from invertebrates exist though it is not always clear if these are true infections of these paratenic hosts or if these are simply larvae hatching in the invertebrate gut and passaging through the gastrointestinal tract (transport hosts). Infections in earthworms and cockroaches have been described. In one instance, T. cati larvae were liberated from the tissue of land snails (Rumina decollata) collected in Argentina (Cardillo et al, 2016), emphasising the need for greater research into the role of gastropods in T. cati transmission. In any case, paratenic or transport hosts both still play a role in transmission to the felid definitive host.

Vertical transmission is also possible. Unlike Toxocara canis in dogs, trans-placental is not an important route of transmission in Toxocara cati, either by artificial (Sprent, 1956) or natural infection (Swerczek et al, 1971) of the queens. In contrast, a small study showed that the only way that transmammary infection of nursing kittens is most likely to occur is if the queens are infected during lactation, with chronic infections being atypical sources of post-natal lactogenic transmission (Coati et al, 2004). However, new infections in queens with outdoor access are not uncommon. Therefore, unlike with T. canis, gestational-related reactivation of somatic larvae with subsequent vertical transmission does not seem to occur (Coati et al, 2004).

Clinical importance in cats

In healthy pet cats there is usually a low worm burden, and infections are typically asymptomatic, discovered only via faecal screening or if worms are spontaneously passed in faeces or vomitus. Those with higher burdens, such as in kittens infected by the transmammary route, may present with poor body condition, pot-bellied appearance, respiratory disorders, diarrhoea, vomiting, and in extreme cases cachexia among other signs as early as 3 weeks of age. Heavy infections may cause intestinal blockage or intussusceptions in kittens, which are potentially fatal (Dantas-Torres et al, 2020). Disease is less frequent but may occasionally occur in adult cats, especially if aberrant migration of adult worms occurs. A report of a domestic 7-year-old male cat that presented with anorexia, vomiting, and an enlarged abdomen, revealed at the laparotomy an adult T. cati in the peritoneum and a gastric ulcer that had perforated the stomach wall (Aoki et al, 1990). Unlike in dogs where patent T. canis infections occur most frequently in puppies, T. cati does not seem to follow the same sharp age stratification in cats and infections are common in both kittens and adult cats (Sharif et al, 2007; Overgaauw and van Knapen, 2013).

Human toxocarosis and the zoonotic potential of Toxocara cati

Even though dog and cat infections with these parasites were described more than two centuries ago, only beginning in the 1950s were T. canis and T. cati recognised as important human pathogens (Rubinsky-Elefant et al, 2010). Human toxocarosis is caused by larval migration of both dog and cat ascarids within the tissues of humans. There are two forms of human toxocarosis: visceral larva migrans and ocular larva migrans, differentiated by the affected body system. The first report of visceral larva migrans was in 1952, in which T. canis larvae were recovered from three children presenting with an eosinophilia-associated disease syndrome in New Orleans, Louisiana (Beaver et al, 1952). The clinical presentation of visceral larva migrans disease in humans, while variable, is classically associated with non-specific signs and symptoms such as fever, cough, hepatomegaly, abdominal pain, and urticaria, often accompanied by peripheral eosinophilia (Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). Migration of larvae to the eyes (ocular larva migrans), which usually occurs in young children, is an important complication that may result in diminished vision, and rarely invasion of the central nervous system by larvae may occur resulting in eosinophilic meningoencephalitis.

Human toxocarosis may be significantly underreported and only infections with severe clinical manifestations are likely to be diagnosed; the vast majority of infections are likely missed due to either mild non-specific clinical signs, or absence of detectable symptoms — particularly in infected adults who may not present with as overt symptoms as children. This underreporting is evident in recent systematic meta analyses that estimate a global seroprevalence of 19%, indicating widespread and frequent exposure to Toxocara spp. across diverse populations and climates (Ma et al, 2020). In industrialised nations such as the United States and the UK, where parasitic infections are often not considered an important problem, estimates of human toxocarosis based on seroprevalence studies have ranged from 5 to 24% (Berrett et al, 2017; Liu et al, 2018; Ma et al, 2020).

It is important to highlight that there are a large number of common antigenic fractions shared between T. canis and T. cati, thus seroprevalence studies may reflect human exposure to either of these parasites. The similarity in the mode of infection also suggest that there is comparable zoonotic potential between these species (Cardillo et al, 2009). One line of epidemiologic evidence can be found in Islamic countries, where dogs are avoided for religious reasons whereas cats are favoured as pets. In these conditions, the seroprevalence of human toxocarosis is comparable to non-Islamic regions with reports of 32% in Egypt, 11% in Jordan (Smith and Noordin, 2006; Ma et al, 2020) Thus, the potential role of T. cati in toxocarosis should not be ignored or underestimated (Fisher, 2003; Overgaauw, 1997). Furthermore, associations appear to exist between Toxocara spp. seropositivity and chronic conditions such as epilepsy and asthma, though this is an area of ongoing investigation (Aghaei et al, 2018; Luna et al, 2018). The broad clinical spectrum of human toxocarosis leads to challenges in clinical diagnosis, underscoring the importance of raising awareness about the risks of Toxocara spp. infections.

A major outstanding question is the role of T. cati in toxocarosis in humans. T. canis is generally considered the typical cause of infection in humans, though T. cati infections are nearly certainly underreported considering the high prevalence in cats and the sheer frequency of human exposure to Toxocara spp. However, extracting a clear number of cases attributable to T. cati specifically is not an easy question to answer, as serologic tools routinely used in the diagnosis of human disease cannot distinguish between T. canis and T. cati (Poulsen et al, 2015). On rare instances where larvae are recovered from vitreal fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, or tissue biopsies, molecular methods and/or morphologic methods may be able to achieve species-level resolution (Wilkins, 2014).

A compendium of the confirmed cases of human toxocarosis by T. cati to date is presented in chronological order in Table 1. However, definitive identification to species level in human cases of Toxocara larva migrans is not commonly achieved and this most certainly represents a vast underestimation of the impact of T. cati in human disease. A few reports exist where adult T. cati were passed in faeces or vomit of young children; these are unlikely to represent cases of true parasitism but are more likely the result of children ingesting these worms from the environment or spurious parasites (Eberhard and Alfano, 1998). However, the faecal-oral exposure sustained in these cases is a cause for concern as it presents a risk of exposure to infectious eggs.

Table 1. Confirmed cases of Toxocara cati infections in humans in chronological order

| Year of report | Country | Age of patient(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1956 | United States | 2 years | (Karpinski Jr et al, 1956) |

| 1964 | Israel | 5 years | (Schoenfield et al, 1964) |

| 1969 | UK | 14 months | (Wiseman and Lovel, 1969) |

| 1975 | Japan | Not provided | (Takeda et al, 1975) |

| 1982 | Japan | 52 years | (Shimokawa et al, 1982) |

| 1990 | Japan | Not provided | (Nagakura et al, 1990) |

| 1991 | Brazil | Children | (Virginia et al, 1991) |

| 1998 | Japan | 38 years | (Sakai et al, 1998) |

| 1999 | Japan | Not provided | (Ueno, 1999) |

| 2014 | Iran | 6 years | (Zibaei et al, 2014) |

The scarcity of species identification in cases of human toxocarosis also leads to outstanding questions that cannot yet be answered adequately. For example, species-level differences in neurological effects (e.g. motor versus behavioural abnormalities) in mice inoculated with T. canis and T. cati have been observed (Janecek et al, 2014), suggesting the need for further characterisation of the full spectrum of T. cati larva migrans in human infections.

Routes of zoonotic transmission

Many potential exposure opportunities of humans to infectious T. cati eggs or larvae exist, further supporting that this is an underreported zoonotic agent. Routes of exposure for humans include ingestion of infectious larvated eggs (whether acquired from contaminated soil or potentially fur) and foodborne transmission via undercooked meat contaminated with encysted larvae. Comparisons of global toxocarosis seroprevalence have revealed risk factors, which may indicate how people are most likely coming into contact with infectious eggs or larvae. In a large meta-analysis, risk factors such as a lower human development index, rural settings, and contact with soil and untreated water were associated with greater seroprevalence in humans — suggesting environmental contamination and general sanitation play an important role in zoonotic transmission. Contact with dogs or cats were also identified as risk factors, along with young age and male gender. Consumption of raw meat or viscera was also found as a moderate risk factor (OR=1.59; 95%; CI 1.03—2.47), suggesting foodborne transmission is playing a smaller but still significant role (Rostami et al, 2019). Perhaps the highest risk is exposure to eggs shed in the faeces of infected cats, which is also supported by the large meta analysis (Rostami et al, 2019). Given the high prevalence in cats globally, this could lead to a great potential for environmental contamination. Many studies have examined soil samples from domestic environments such as gardens, playgrounds, and parks for the presence of Toxocara spp. eggs, with up to 66% of individual soil samples being contaminated in some locations (Fisher, 2003). Relatively few studies differentiate species of Toxocara spp. eggs recovered from the environment. However, in Poland, T. cati eggs were recovered more frequently than T. canis eggs in urban areas (primarily backyards); and in an urban setting in Iran, T. cati eggs were recovered five times more frequently than those of T. canis (Khademvatan et al, 2014; Mizgajska-Wiktor et al, 2017). This further supports that the risk of human exposure to T. cati should not be underestimated. Also, as ascarid eggs are environmentally hardy and can remain infectious for extended periods of time, possibly even for years (Azam et al, 2012), decontamination of areas frequented by infected cats may prove difficult (Overgaauw and van Knapen, 2013).

A plethora of studies have suggested that direct contact with the fur of an infected dog may be an important zoonotic source of T. canis eggs (Wolfe and Wright, 2003; Aydenizöz-Özkayhan et al, 2008; Roddie et al, 2008). A smaller number of studies have examined T. cati in this respect, and also reported that contamination of hair does occur in cats (Bakhshani et al, 2019). However, even though a low percentage of eggs in fur are embryonated, they are mostly not viable. In addition, Toxocara spp. eggs are very adhesive and difficult to remove from dog or cat hair, which decreases the probability of being accidentally swallowed by a person. Even in the worst-case scenario of an animal with highly contaminated fur, several grams of hair would need to be ingested to present a significant risk of infection (Overgaauw et al, 2009; Keegan and Holland, 2013). Still, it is always advisable to thoroughly wash hands after petting, touching, or handling an animal and especially before eating or preparing food.

The foodborne route of infection is also an area of interest for T. cati. Previous foodborne Toxocara spp. confirmed infections (usually assumed to be T. canis) have resulted from consumption of undercooked poultry, waterfowl, beef, and lamb — though the offending product is usually liver or other viscera in areas where such dishes are popular, as opposed to the meat of the skeletal muscle (Hoffmeister et al, 2007; Choi et al, 2008; Lim, 2012). However, T. cati larvae have experimentally been shown to migrate to and accumulate in skeletal muscle of paratenic hosts. Studies infecting chickens with 3000 embryonated eggs showed that the initial establishment (1–3 days post-infection) takes place in the liver and lungs, thereafter (3 days post-infection and onwards) a gradual migration to and accumulation in muscles takes place. No clinical signs of the infection or changes in behaviour were observed in the poultry during the experiments. Subsequently, to assess infectivity of the larvae recovered, seven male 5-week-old mice were inoculated with 175 to 176 days old larvae. At 14 days, larvae were recovered from all mice inoculated with 22 T. cati larvae from chicken muscles, with a mean recovery rate of 52.9%. These data demonstrate that T. cati larvae persist in chicken muscles for a long period of time and that these larvae remain infective (Taira et al, 2011). Furthermore, storage of chicken meat containing T. cati larvae at refrigeration temperature (4°C) for 3–4 weeks still proved infectious when fed to mice; however, freezing (-25°C) for at least 12 hours seemed sufficient to inactivate larvae. Cooking meat to recommended safe internal temperatures will also inactivate larvae.

As a result of the large number of common antigenic fractions shared between T. canis and T. cati, and the similarity in the mode of infection, these are indications that there is comparable zoonotic potential between these species (Cardillo et al, 2009). One line of epidemiologic evidence can be found in Islamic countries, where dogs are avoided for religious reasons whereas cats are favoured as pets. In these conditions, the seroprevalence of toxocarosis in humans can be considerable (Smith and Noordin, 2006; Ma et al, 2020) (e.g. 32% in Egypt, 11% in Jordan). Thus, the potential role of T. cati in toxocarosis in humans should not be ignored or underestimated (Overgaauw, 1997; Fisher, 2003).

Diagnosis in cats and humans

The detection of Toxocara spp. in cats is an important step in controlling infections and preventing zoonotic exposure. T. cati and T. canis show a high degree of host specificity, with cats and dogs as the definitive hosts respectively. However, a recent report showed evidence that cross-infections could take place (Fava et al, 2020). T. cati infections in cats can be confirmed by standard faecal flotation, coproantigen test, or morphologically if the adults are recovered. Eggs are 70 μm x 80 μm and with a pitted shell (Figure 2) (Dantas-Torres et al, 2020). The adult worms are brownish yellow, or cream coloured to pinkish and have a length of up to 10 cm. These have distinct cervical alae that are short and wide, giving the anterior end the distinctive appearance of an arrowhead. The oesophagus is around 2–6% of the total body length and finishes in a glandular ventriculus that is 0.3–0.5 mm long, with the vulva opening of the female located at 25–40% of the body length from the anterior end. The spicules of the males range from 1.7–1.9 mm in length (Bowman et al, 2002). These may be observed in the vomitus or faeces of infected cats (Figures 3 and 4).

The authors recommend performing an in-clinic faecal flotation with centrifugation, following the procedure described by the Companion Animal Parasite Council www.capcvet.org/guidelines/ascarid/

Faecal flotation with centrifugation

Diagnosis of patent ascarid infections via faecal flotation is straightforward. Ascarids are prolific egg producers and the eggs float readily in most flotation solutions for parasite microscopy:

- Mix 1 to 5 g of faeces and 10 ml of flotation solution (ZnSO4 specific gravity 1.18; sugar specific gravity 1.25) and filter/strain into a 15 ml centrifuge tube

- Top off with flotation solution to form a slightly positive meniscus, add coverslip, and centrifuge for 5 minutes at 1500 to 2000 rpm. Eggs can be microscopically detected in the coverslip.

To perform the coproantigen test, the authors recommend contacting the manufacturer https://www.idexx.co.uk/en-gb/search/?q=coproantigen. In a recent study carried out in the US comparing the faecal flotation and the coproantigen immunoassay, the proportion of positive tests was significantly higher by coproantigen than by centrifugation (Sweet et al, 2020). Furthermore, the former uses enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technology to detect antigens secreted or excreted by the parasite of interest and these are unique to the mature, metabolically active parasites and do not cross-react with eggs (Elsemore et al, 2014, 2017) and increase sensitivity (Little, 2019); and faecal flotation can give false positives through coprophagia. For these reasons, the authors recommend using antigen detection assays in conjunction with faecal flotation centrifugation to increase the diagnostic sensitivity of intestinal parasites.

The preferred diagnostic strategy for toxocarosis in humans is based on a combination of clinical evidence and antibody detection in serum or vitreous humour. For more on the diagnosis of human toxocarosis, please visit the DPDx website maintained by the CDC: https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/toxocariasis/index.html

Control and prevention strategies

Currently, there is a variety of anthelmintic products available in the global market. Public databases such as www.noahcompendium.co.uk or www.vmd.defra.gov.uk should be consulted to check which products are registered and available in the UK market. For anthelmintic treatment options, and to know which are effective against ascarids, refer to Table 2, this table is publicly available in the www.troccap.com website (Dantas-Torres et al, 2020).

Table 2. Routes of administration, dosage and efficacies of commonly used anthelminthic products against the primary endoparasites of cats Dantas-Torres et al, 2020

| Anthelminthic | Route | Dosage | Roundworm | Hookworm | Tapeworm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrantel pamoate | PO | 20 mg/kg pyrantel pamoate | Yes | Yes | |

| Pyrantel embonate | PO | 57.5 mg/kg pyrantel embonate | Yes | Yes | |

| Emodepside* | Topical | 3 mg/kg emodepside | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Praziquantel | PO, SC, IM | 5–10 mg/kg | Yes | ||

| Praziquantel | Topical | 8 mg/kg | Yes | ||

| Fenbendazole** | PO | 50 mg/kg daily for 3–5 days | Yes | Yes | |

| Ivermectin | PO | 0.024 mg/kg | Yes | ||

| Milbemycin oxime* | PO | 2 mg/kg | Yes | Yes | |

| Selamectin | Topical | 6 mg/kg | Yes | Yes | |

| Epsiprantel | PO | 2.75 mg/kg | Yes | ||

| Moxidectin** | Topical | 1 mg/kg moxidectin | Yes | Yes | |

| Eprinomectin* | PO | 0.5 mg/kg | Yes | Yes |

Effective against whipworms and stomach worms.

PO = per os, SC = subcutaneous, IM = intramuscular

The prevention of environmental contamination with eggs is essential to minimise the infection risk to other animals or humans. This is especially important given the high environmental hardiness of Toxocara eggs and the difficulty in remediating contaminated soil or other substrates that are not readily or effectively treated (i.e. with heat or certain disinfectants) (Morrondo et al, 2006; Keegan and Holland, 2013). Current guidelines of associations such as the European Scientific Counsel of Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP; www.esccap.org), the Tropical Council for Companion Animal Parasites (TroCCAP; www.troccap.com), or the Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC; www.capcvet.org) should be followed and implemented. The most important points are as follows:

- Routine deworming of kittens from 2 weeks of age (every 2 weeks until 4—8 weeks of age), and monthly preventives after that

- Monitoring of efficacy of deworming and monthly preventives via faecal examination 2–4 times a year for kittens (<1 year old) and once or twice per year for cats older than 1 year

- Keeping cats indoors is advised to restrict hunting of potential intermediate/paratenic hosts and to reduce exposure to environments contaminated by eggs from other infected free-roaming cats. Feeding only commercially prepared, cooked diets is also advisable

- Removing cat faeces from the environment in a timely manner is important to prevent development of eggs to the infectious stage. Restricting access of cats to areas where children may be at risk for exposure (e.g. sandboxes, playgrounds) is also recommended.

Knowledge and attitudes towards parasite control

Many surveys of veterinarians’ and owners’ awareness and risk perception of parasites — Toxocara included — have been conducted and revealed sometimes less than satisfactory adherence and communication.

Improving client awareness is clearly necessary, as cat owners may not be administering preventatives as often as necessary to prevent infection (Pennelegion et al, 2020). Recent surveys of cat owners in various European countries revealed an average of only 3.1 deworming events per year among pet cats in the UK, and 2.25 times per year in France, 1.7 times per year in Germany, and 2.0 times per year in Spain, falling well short of ESCCAP's recommended >4 times per year (with monthly prevention preferred) (Roussel et al, 2019; Strube et al, 2019Miró et al, 2020; Pennelegion et al, 2020). This is despite, in many cases, cats having owner-reported behavioural/lifestyle risk factors that would increase exposure to T. cati (e.g. being allowed outdoors, hunting prey, being fed raw meat) (Roussel et al, 2019).

Knowledge of human toxocarosis has been found to be limited both among pet owners and non-owners (Kantarakia et al, 2020). In one survey, the chief reason for deworming cats was stated as the health of the animal, whereas only 10.8% reported for public health/risk of human exposure (Nijsse et al, 2016). While it is commendable that cat owners clearly care for their pets, this could indicate a lack of awareness of the potentially grave risks of human toxocarosis. Among the more recent European studies, it was found that cats are dewormed with less frequency than dogs; this could be for many reasons (e.g. higher monetary value of dogs, awareness of canine heartworm disease), but could also indicate that infections in cats are not perceived as great a threat to human health as those in dogs. In targeting pet owners, increasing risk awareness may then help to improve the adherence to monthly deworming schedules, and veterinarians should play a critical role in client education.

Importantly, all veterinarian recommended protocols should be reviewed to ensure that they begin early enough to prevent egg shedding and are frequent enough to prevent re-exposure. In some surveys, less than half of participating veterinarians recommended protocols and/or discussed the risk of zoonotic infection with clients. Continuing education for veterinarians may be necessary to ensure quality and accuracy of recommendations (Stull, 2007).

Conclusion

In the past, there has been an assumption that T. canis was the most likely cause of Toxocara spp.-related disease. However, given the widespread nature of T. cati in pet and feral cats, along with reported insufficient control measures, it remains almost certain that T. cati is responsible for an underestimated proportion of these cases. Though the identification of T. cati infections in humans remains challenging, it remains important to educate cat owners on the potential risks and control strategies. Continuing to improve awareness and prevention measures among both veterinarians and clients is critical.

KEY POINTS

- The feline ascarid, Toxocara cati, is often considered as one of the most prevalent helminth parasites of domestic cats.

- Unlike Toxocara canis in dogs, trans-placental is not an important route of transmission in T. cati, either by artificial or natural infection.

- There are two forms of toxocarosis: visceral larva migrans and ocular larva migrans, differentiated by the affected body system.

- Cooking meat to recommended safe internal temperatures will inactivate larvae.

- The detection of Toxocara spp. in cats is an important step in controlling infections and preventing zoonotic exposure.

- Though the identification of T. cati toxocarosis in humans remains challenging, it remains important to educate cat owners on the potential risks and control strategies.