The term compliance is familar to all in veterinary practice, but its meaning is somewhat ambiguous. As such, it is understandable that veterinary surgeons may struggle to engage with the subject of owner compliance despite it being an issue that profoundly impacts the health and welfare of their patients. The round-table discussion outlined below was held on 18 March to discuss and investigate the ongoing dilemmas of what is meant by owner compliance, and how to achieve good owner compliance with both acute and chronic treatment protocols as well as long-term preventative regimens prescribed by veterinary surgeons for cats and dogs.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that only 50% of human patients comply with treatment recommendations (WHO, 2003). Owner compliance is less well studied in veterinary medicine and investigations are less robust; however, similar trends of low rates of owner compliance have been identified (Barter et al, 1996a,b; Grave and Tanem, 1999; Amberg-Alraun, 2003, 2004; Adams et al, 2005; Booth et al, 2021). The practical challenges are well recognised; the International Society of Feline Medicine (ISFM) have developed an ‘easy to give’ campaign to encourage the production of more suitable feline medicines and manufacturers are being increasingly creative in developing formulations that are better accepted by pets (ISFM, n.d.). Owner compliance is a day-to-day problem for veterinary surgeons in practice and this document aims to define the challenges faced in practice and propose concepts and mechanisms by which compliance may be improved.

Why is owner compliance important?

All medicines are prescribed for a reason and if they are not administered then the patient will derive no benefit. Poor compliance has a devastating impact on human health; in the USA it is estimated that poor medication compliance costs $100 billion per annum in avoidable hospitalisation fees (Kleinsinger, 2018). Conversely, increased drug utilisation can provide a net economic return when it is driven by improved adherence with guidelines-based therapy (Sokol et al, 2005). Also in the USA, failure to take prescribed antihypertensive medication is estimated to result in 89000 premature deaths annually (Network for Excellence in Health Innovation (NEHI), n.d.). In human healthcare 25% of patients fail to adhere to treatment for osteoarthritis or hyperlipidaemia (Cheen et al, 2019). Following cardiac transplant, 5–39% of patients fail to follow postoperative treatment protocols (Lieb et al, 2020).

In veterinary species poor compliance has a number of potential impacts:

- Failure to manage the patient's primary clinical complaint

- Increased risk of recurrence of disease

- Poor management of chronic disease, e.g. epilepsy, osteoarthritis, atopy, chemotherapy, cardiac disease

- Failure to prevent disease with preventative regimens (e.g. parasite protection)

- Increased risk of antimicrobial resistance

- Adverse effects associated with sudden medicine withdrawal

- Adverse effects associated with toxicity if attempts are made to ‘catch-up’

- Increased costs associated with treatment failure and leading to more intensive treatment regimens — higher doses, more potent medications, more professional fees

- Loss of confidence in veterinary medicines

- Loss of confidence in the veterinary surgeon/practice

- Accumulation of medication in the home that presents a risk for inappropriate use or accidental poisoning in the future

- Ecotoxicity associated with inappropriate disposal of medicines.

Understanding why owners do not administer the medicines that are prescribed to their pets may lead to more effective treatment and improvements in patient care.

Defining compliance

In human healthcare the terms compliance, adherence and concordance are used widely. Treharne et al (2006) proposed the following definitions:

Compliance

The paternalistic view that the person is a passive party who has his or her prescribed treatment enforced

Adherence

The (still paternalistic) view that the informed (but still passive) person will stick to taking recommended treatment

Concordance

The process of enlightened communication between the person and the health professional leading to an agreed treatment and ongoing assessment of the optimal course.

At the time when these were proposed a paternalistic angle was presumed, and while these definitions are interesting, culture has changed.

Compliance is the best understood term in veterinary medicine, but has the negative connotation that the animal owner is entirely passive and is simply expected to follow instructions without questioning them.

Adherence suggests that the owner is informed of what they are doing and why but remains a passive party. This definition of adherence better describes the vet–client relationship but the term adherence is not considered to be well used or understood in veterinary practice.

Concordance is an appealing concept that should be the goal in any healthcare setting.

However, it is difficult to define, measure and articulate in practice. The term is not intuitive, is used differently and creates barriers.

It is essential that the concepts of concordance and ‘consensus based’ or shared decision-making are embraced, but the ultimate measure of whether or not this results in patients receiving the appropriate medication remains best described as ‘compliance’, given that the term is universally recognised and understood. The importance of shared decision-making in optimising compliance is universally recognised.

‘Shared decision-making must become the norm …to better reflect the principle of ‘no decision about me without me’

‘Foster a common culture shared by all in the service of putting the patient first’

‘Today, person-centred care is also central to the policies of the four UK countries. The Health and Social Care Act 2012 imposes a legal duty for NHS England and clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) to involve patients in their care.’

(The Health Foundation, 2016).

In many veterinary schools, the undergraduate syllabus now contains teaching on the importance of shared decision-making. Veterinary surgeons have to seek consent from pet owners, and shared decision-making is now the expected norm. Pet owners need to be involved in decision-making to provide consent for fees that are to be incurred or informed consent for procedures or the use of off-label medicines. However, it is important that veterinary surgeons go further and ensure that clients are involved in all aspects of decision-making, particularly whether it is feasible and realistic for them to administer the treatments or make the management changes that are felt necessary.

Owner compliance in veterinary medicine can be defined as: the giving of a medicine or medication as agreed and planned.

Compliance is often considered binary, i.e. an animal is either compliant or not, but the reality is far more complex.

Why is poor owner compliance a problem?

A number of factors have been associated with poor compliance in human healthcare:

- Stigma

- Medication costs

- Transportation to acquire medication

- Depression

- Lower social support

- Lower quality of life

- Lower socioeconomic status

- Non-white ethnicity

- Negative feelings/attitudes to medication or treatment

- Higher frequency of medication intake

- Time since prescription

- Anxiety

- Male gender (not always)

- Lower self-efficacy and low external locus of control

- General mental comorbidity

- Being a younger adult or geriatric.

These factors may be broadly classified into:

- Practical

- Psychological

- Pathological

- Personal

- Political

- Societal

- Cultural

- Random.

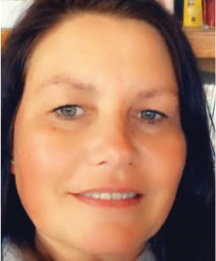

These factors can be classified as personal (internal) or societal (external) and as easy or difficult to mitigate, as summarised in Figure 1.

Many of these factors are likely to apply to pet owners and while these are associated with human healthcare in general, there are clear parallels between veterinary and paediatric medicine in which the healthcare provider is reliant on a responsible third party to give the medication to the patient. There are layers of reasons why pet owners may not comply from absent-mindedness to conscious objection. Human decision-making is not strictly rational, as defined by economists (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974), although the use of a heuristic approach to decision-making is rational, reducing the cognitive effort required to make the thousands of decisions we make every day. In addition, the pet owner's assessment of the value of treatment may be neither logical nor objective. The effect of placebos is well documented and two placebos have been shown to be more effective than a single placebo (Benedetti, 2009).

However, actions are likely to be influenced by knowledge, beliefs and patterns of behaviour as well as more practical factors, such as capability and opportunity. According to the theory of planned behaviour: behaviour, attitude, subjective normal and perceived behavioural control will predict the intention to perform a behaviour. In turn, intention should be a reliable predictor of compliance.

Nevertheless, the concept of an ‘intention–action’ gap (Papies, 2017) is well recognised — while people know that they should do something they may not do it. Intentions and planned behaviour do not always lead to behaviour change (Azjen, 1991). Greater knowledge is associated with improved compliance; however, greater knowledge or changes in attitude again do not always result in behaviour change (Michie and West, 2013).

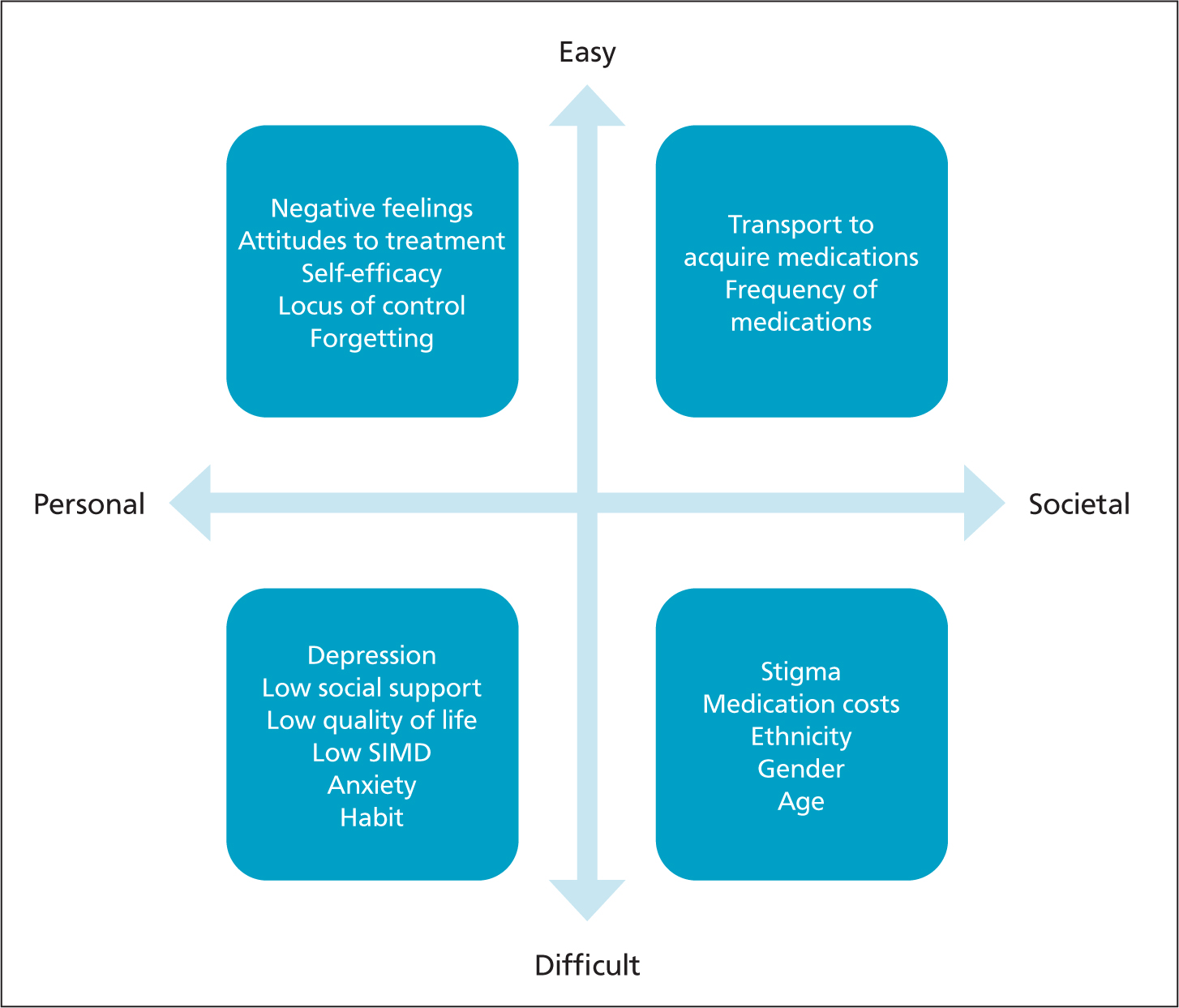

How do we change behaviour?

There are many different models that are used to explain human behaviour and the intention–action gap. Two models that could be useful to veterinary practice are the COM-B model and the Fogg Behavior Model. The COM-B model (Michie et al, 2014) is helpful in highlighting the factors that may influence compliance (Figure 2). The likelihood of a Behaviour (B) is determined by the Capability (C), Opportunity (O) and Motivation (M) that someone has to perform it. To comply with a treatment regimen, the owner has to be motivated to want to administer the medication and has to be mentally and physically able to administer the medication without too much difficulty. This is a bit of an over-simplification — in practice these factors may not all be present at once; for example, the owner might have a low level of motivation but if the task is really easy to complete (opportunity) then all will be fine; however, if they do not really have the opportunity (e.g. they have to go out of their way to complete a task), then a higher level of motivation is needed to compensate. The social environment will also exert a strong stimulus, and owners will likely be influenced by what they perceive other owners around them think and do, and how their pet reacts to the act of administering of the medication.

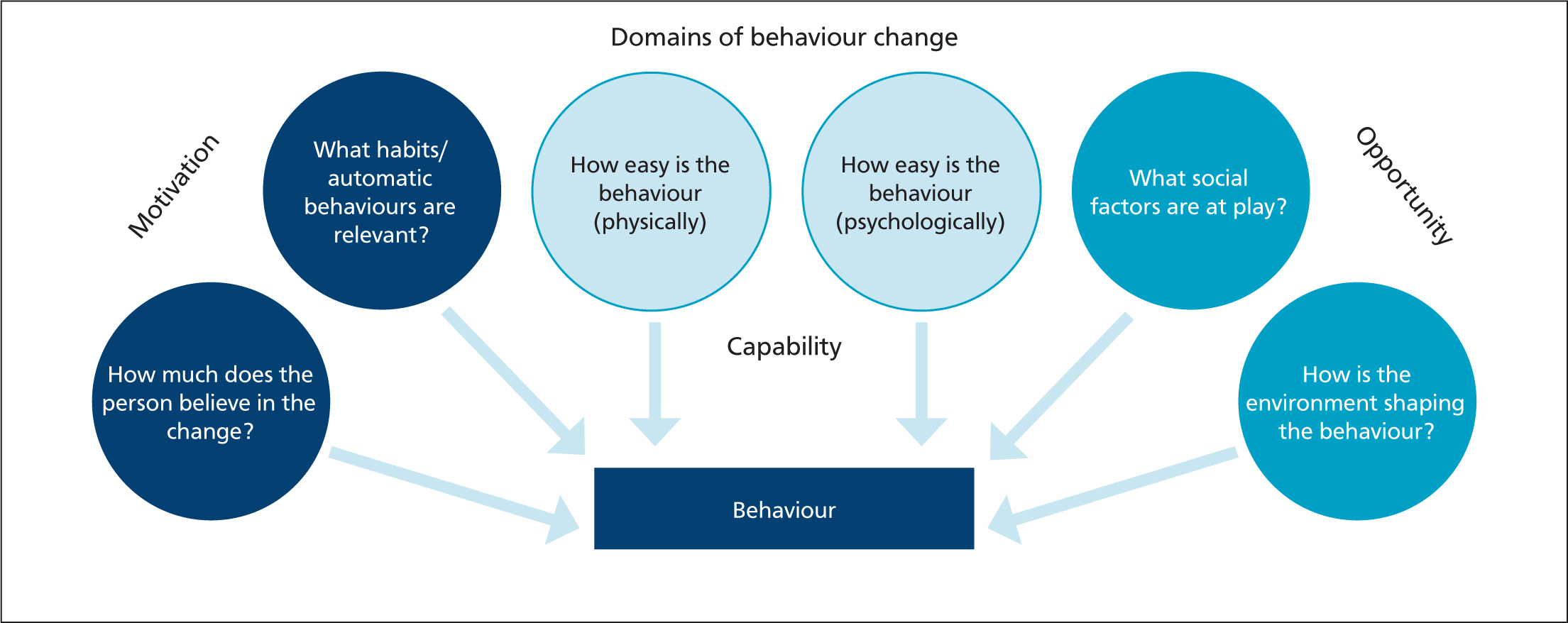

The behaviour change model described by Fogg (2009) (https://www.behaviormodel.org/ and https://www.behaviorgrid.org/) highlights the combined importance of motivation and ability in determining behaviour (Figure 3). Interventions, or prompts, may be doomed to fail if the owner does not have sufficient motivation to administer a medication or has insufficient ability to be able to administer as intended (Figure 4).

Evidence from veterinary medicine reflects the human literature in identifying the importance of support and empowerment of pet owners in promoting management change. Studies of equine and canine obesity have demonstrated the value of tailoring treatment and supporting decision making (German et al, 2016; Furtado et al, 2020). Human studies of motivational interviewing have consistently demonstrated that empathy and empowerment are predictors of behavioural change; confrontation is the single biggest predictor of failure (White and Miller, 2007; Miller and Rollnick, 2014). The importance of empathy and listening reinforces the evidence that empowerment and control are associated with improved compliance.

It is worth noting that within the research the majority of interventions take a very cognitive approach to compliance. For example, either focusing on education (telling people why they should do something), or on behaviour (training and practice). More psychological-based interventions are relatively rare, such as testing different ways of framing the same request or using implementation intentions.

The role of the animal itself is also important in determining compliance. If animals respond negatively to the intervention then any negative feelings that the owner has toward the treatment will be reinforced and there is a risk of progressively decreasing compliance. For example, tabletting a cat is likely to be a negative experience and may become progressively more difficult. By contrast, giving a meat-flavoured chewable tablet to a dog is likely to be a positive experience and the positives of administering the medication will be reinforced (Figure 5).

Optimising owner compliance

While every healthcare professional likes to think that they know their patients, doctors' ability to predict compliance has been reported to be no better than chance (Barter et al, 1996b; Byerly et al, 2005). However, nurses may have a much better ability to predict compliance as they have a different and less formal relationship with patients. There is no reason to suspect that veterinary surgeons are any better at predicting compliance than medics and we should not be complacent in assuming compliance. If time allows, there may be a tendency to make more effort in discussing compliance with cat owners than dog owners given the difficulties of medicating cats, but we should be cognisant of the high rate of non-compliance in all patient and owner groups. Veterinary surgeons will be unaware of low rates of compliance as regrettably it is very challenging to quantify missed medication or missed follow-up appointments in most practices. It is often the case that the focus is on the patients that are seen regularly, not those that fail to attend the practice. The refinement of practice management software to highlight and capture information on delayed requests for repeat prescriptions or missed follow-up appointments would be highly beneficial to veterinary practices and would offer commercial as well as welfare benefits.

The relationship between pet owner and healthcare professional has a huge bearing on subsequent compliance. In human healthcare it is recognised that patients are more likely to comply if they see a doctor that they like and feel that they have been listened to. Studies have indicated that it is more important for the professional to be liked than to be respected (Howard et al, 1970; Garrity, 1981). If owners feel that they are being dictated to then there is a tendency for them to try and re-assert control and they may do so by ignoring the advice or prescription that is being provided — an effect known as reactance theory (Brehm, 1966). The strength of the professional–client relationship can also stand in the way of obtaining truthful answers, meaning that owners may be reluctant to admit that they have not followed instructions for fear of letting down or disappointing someone they like or respect.

Owners may be more open and honest with veterinary nurses or receptionists than they are with veterinary surgeons; the relationship is different and this is something that veterinary practices should take advantage of. It should be considered that the care of a pet is a team effort involving all members of the practice. Greater contact between owners and nurses at the point of dispensing, and ideally regularly thereafter, empowers owners, supports them and provides them with an opportunity to raise concerns around compliance or treatment response. It is frequently impossible to have sufficient discussion and to allow the owner to feel listened to and empowered within a 10–20 minute veterinary consultation. It is therefore important that owners are given the opportunity to have complementary appointments/conversations with a veterinary nurse. There are clear commercial arguments for increasing the amount of time owners spend with veterinary nurses, since it has been estimated that the annual client spend of bonded clients can be, on average, up to three times that of casual clients (Robinson, 2014). Consistency of message between different members of the team is important; lack of consistency undermines confidence in the value of the intervention.

There are no studies on the impact of cost in veterinary practice — and the variable of cost is not an issue that is well studied in the UK in healthcare, as human healthcare is free at the point of care. In the USA, there is evidence of patients changing their treatment regimens to reduce the cost of medication (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019). Cost is clearly an important factor in decision-making around treatment, however, it is unclear how it influences compliance once a treatment plan with an accurate estimate of cost has been agreed. Anecdotally, it is not uncommon for owners to fail to collect medicines they have paid for, particularly preventive treatments, so cost in some cases may not be a relevant factor. However, cost may be a greater factor in the management of chronic disease in which owners may have a tendency to withdraw treatment when clinical signs improve, allowing the condition to deteriorate, resulting in a return of clinical signs.

Anecdotally, many owners will, within reasonable limits, prioritise ease of administration over cost. The physical difficulty of medicating pets is a major factor in limiting compliance. It has been demonstrated in the paediatric literature that a child's reaction to medication is an important determinant of compliance and it is likely that the same is true in the owner–pet relationship (Burgess et al, 2008). Formulations that can be given without a negative reaction (e.g. palatable liquids for cats) or ideally are associated with a positive reaction (e.g. chewable ‘treat’ tablets for dogs) would be expected to result in better compliance.

The bioavailability of some medications is affected by feeding and advice is often given that medication should not be given with food. This may be taken too literally and simply making owners aware that they can give medication disguised within a treat could make the process far more positive.

When developing treatment protocols, it is essential that owners understand the decisions taken and are empowered as part of the process. It is equally important that they are consulted to determine what is physically and socially possible for them. Treatment regimens have to be compatible with the owners' habits and routines or there is an increased risk of non-compliance. Owners have to be confident and capable of administering a spot-on or giving a tablet, with practices not assuming that owners possess the necessary knowledge and skills. If owners have concerns over their abilities, then there is a greater risk of non-compliance, as shown in the COM-B model discussed earlier (Figure 3).

The manner in which questions are asked is also important — questioning must be without presumption. If owners are given the impression that they should be able to do something, then they may be reluctant to admit that they cannot do it or do not know how to. Suggesting that there may be practical difficulties in administering a medication to a pet rather than suggesting an owner is unable to do it is far better. Using positive terminology and being positive about the treatment protocol in general is important.

It is also important that owners are aware of the negative impacts of non-compliance. In most situations, people intuitively ‘frame’ information in terms of what's called a ‘gain frame’ — by focusing on the benefits of following the advice; for example, ‘we have the opportunity to delay heart failure by starting Mya on a course of XXX now’. However, opting to use a ‘loss frame’ which emphasises the cost of not engaging in the target behaviour has been shown to be far more effective. For example, ‘If we do nothing then Mya is likely to experience heart failure a lot sooner’. This is because from a psychological perspective, losses loom larger than gains.

As previously discussed, a potential reason why people fail to administer drugs to their pets is because they simply forget. Most people have fixed daily routines and giving medication to a pet may not fit into it. However, by giving medication to the pet at a different time each day, we never learn to establish a habit. But if we learn to pair giving the medication with an already established habit, for example, our first cup of coffee in morning, compliance can increase dramatically. Previous research in human medicine into the use of these implementation intentions has shown that the percentage of patients who take the correct dose and on schedule increases to 78.8% compared with just 55.3% in the control condition (Brown et al, 2009). This occurs because our first cup of coffee acts as a cue to trigger the new behaviour. ‘If I'm drinking my first cup of coffee in the morning, then I need to give Mya her pill.’

There will be differences in the relative importance of different factors in determining compliance according to whether the treatment is short-term, long-term (potentially lifelong) or is a preventative medicine aimed at preventing a problem from developing in the first place, e.g. regular administration of preventative worming or flea control.

Improving owner compliance with short-term treatments

Methods to improve owner compliance with short-term treatments include:

- Positive reinforcement

- Listen

- Offer support

- Clear goal setting

- Making it easy

- Reduce frequency of medication

- Use the most straightforward medication or route of administration

- Ask whether it is manageable

- Ensure owners have the prerequisite practical skills (Figure 6)

- Consider supporting owners with ‘training’ behaviour to make medication administration easier for both owner and pet

- Consider providing dosing boxes with each daily medication or combination of medications.

Improving owner compliance with long-term treatments

Methods to improve owner compliance with long-term treatments include:

- Tailor treatment for prolonged change considering

- Habits

- Routines

- Social stimuli

- Provide regular support and re-enforcement.

There is a tendency for owners to discontinue treatments when obvious, visible signs improve and then naturally the disease recurs, e.g. arthritic pain, atopy, epilepsy. Some treatments are the victim of their own success if they produce a profound response initially. It is therefore beneficial to continue working with clients to ensure they understanding the importance of continued compliance in order avoid reappearance of symptoms.

Improving owner compliance with preventative medicine

Methods to improve owner compliance with preventative medicines include:

- Considering the physical and social environment

- Automating behaviour through habits and routines

- Education

- Motivation

- Regular reminders and support

- The less frequent a treatment is administered the more likely it is to be forgotten

- Reminder apps work (Patton et al, 2021)

- One reminder is often insufficient

- Regular contact with the practice

- Emphasise the social normals of providing preventive healthcare.

The role of health plans

Maintaining compliance in the management of chronic diseases and with the administration of preventative medicines is particularly challenging. Compliance is expected to increase with increased contact with the veterinary practice. If clients are paying for a package of healthcare rather than individual consultations or treatments, they are more likely to attend the practice and discuss the management of chronic conditions or the need for preventative healthcare. Many clients (and a good number of veterinary surgeons) take the cynical view that health plans are a means of increasing practice income. They should primarily be a means of improving patient welfare by breaking down some of the financial barriers that reduce contact between owner and veterinary practice. Charging for health plans should be structured in such a way that there are health benefits to the pet, and clients clearly benefit financially from enrolling in them, so that every member of the practice can recommend them without hesitation. Well-considered health plans are a true win–win for all parties: pets benefit from receiving consistent prophylactic treatment, clients will get more for their money, but they will also spend more on extras that they might otherwise have purchased else-where or may not have purchased at all to the detriment of their pets, thus benefiting the practice. They also facilitate the issuing of reminders. If owners are on health plans there is less demand on veterinary surgeons to be having the same conversations about preventative medicine and management or chronic conditions which increases efficiency. Health plans can be tailored to individual patients or patient groups to further improve the potential benefits to the patient. Healthcare plans therefore have the potential to improve compliance by increasing contact, improving knowledge and trust, facilitating reminders, and reducing costs.

Veterinary surgeons often feel awkward about selling services such as health plans. Having members of the practice team that are committed to the benefits of such plans is the most important factor in determining the frequency of their uptake. Members of the practice team need to believe in the health plans to see past the negative connotations of ‘selling’, and focus on the healthcare benefits to the patient of having them enrolled within a programme that allows the veterinary practice to be more closely involved in their medical care.

When selling health plans, veterinary surgeons have a tendency to focus on the rational benefits they offer, but this overlooks how people make decisions. When making a choice, consumers are looking for reassurance that they are not making a mistake, and this reassurance can come from how other people behave. If we are told that ‘most of our owners have already signed up to a health plan’, this helps provide this reassurance. We intuitively think ‘well, if everyone is signing up to a health plan, it can't be such a bad idea’. These social norms-based campaigns consistently outperform cognitive-based campaigns. For example, when it comes to motivating people to engage in environmentally sustainable behaviour, cognitive appeals typically have a compliance rate of 35.1% whereas campaigns that use a social normal appeal (simply saying that most consumers engage in the target behaviour) have a 44.1% compliance rate (Goldstein et al, 2008).

Conclusions

Owner compliance within veterinary practice can be seen as the administration of a medication to their pet or use of a medication as agreed and planned. This agreement and planning should take into consideration among other things the pet's species and personality, the owner's lifestyle and ability, as well as the specifics of the medication being given.

KEY POINT

- Owner compliance in veterinary medicine can be defined as the giving of a medicine or medication as agreed and planned.

- The ‘intention gap’ is a well-recognised concept — while people know that they should do something, they do not always do it.

- Greater knowledge is associated with improved compliance.

- A combination of motivation and ability are important in ensuring owner compliance.

- Tailoring treatment and supporting decision making are also important factors.

- Formulations that can be given without a negative reaction, or that are associated with a positive reaction, would be expected to result in better compliance.

- Owners should be involved in developing treatment protocols and feel empowered, able and confident.

- Owners should be aware of the negative impacts of non-compliance.

- Pairing administration of a medication with an already established habit will likely increase compliance.