The term ‘feline chronic enteropathy’ covers a heterogeneous range of conditions of different aetiologies, including food-responsive enteropathies, corticosteroid-responsive inflammatory bowel disease and antibiotic-responsive diarrhoea (Makielski et al, 2019). Management of any feline chronic enteropathy is not complete without consideration of appropriate dietary support, which may completely resolve the cause and consequent clinical signs in some instances (such as where a dietary allergy is present). However, even in cases where diet is not the cause of the chronic enteropathy, appropriate nutritional support as an adjunct to other therapy is essential to optimise the long-term management of gastrointestinal disease. Diet can also be extremely useful as a diagnostic tool in some cases. The main dietary options for cats with chronic enteropathy and the evidence supporting their use, are explored in this article.

Most forms of feline chronic enteropathy are thought to involve a complex interplay among host genetics, the intestinal microenvironment (primarily bacteria and dietary constituents) and the immune system (Allenspach, 2011). However, distinguishing the underlying cause of the clinical signs (whether food-responsive enteropathies, corticosteroid-responsive inflammatory bowel disease, antibiotic-responsive diarrhoea or other) can be difficult, even aft er undertaking diagnostics including gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy, biopsy and histopathological review of the GI tissue. A number of cats with chronic enteropathy may have disease in other organs in addition to the intestines, particularly the liver and/or pancreas (so called ‘feline triaditis’). Clinical signs oft en overlap in chronic enteropathy and all forms commonly present with persistent and recurrent gastrointestinal signs, including chronic diarrhoea (diarrhoea present for 2–3 weeks or longer) in clinical practice. Differentiating whether the diarrhoea is small or large intestinal in origin can help identify differentials and guide the approach to diagnostic investigations and potential management strategies. Many cases of chronic enteropathy also present with chronic vomiting.

If a cat is severely unwell and has suffered chronic weight loss, there is suspicion of a protein-losing enteropathy (for example, hypoalbuminaemia, which is relatively rare in cats compared to dogs). If there is abnormal abdominal palpation, then full investigations may need to be performed more urgently. However, in otherwise clinically stable cats, it may be reasonable to stage diagnostics and treatments and a diet trial can, and often should be, undertaken early on. Diet is thought to be of potential benefit in a range of chronic enteropathies, and a diet trial relatively early in the diagnostic investigation process may be helpful. Up to 50% of cats with chronic idiopathic GI problems may have a food sensitivity (defined as a food allergy or food intolerance) and could therefore benefit from dietary modification (Guilford et al, 2001). Improvements should be seen within just 2 weeks of starting an appropriate diet (Guilford et al, 2001). This can be helpful when setting owner expectations.

What dietary options are available?

Three dietary options can be considered when trying to diagnose a food-responsive chronic enteropathy or selecting a diet that may help support a cat with chronic enteropathy (Box 1):

- Highly digestible diets

- Hydrolysed diets

- Novel protein diets.

Box 1.Types of dietary approachesThree main dietary approaches exist for cats with chronic enteropathies. These may help to diagnose a food-responsive enteropathy, and/or be used for long term dietary support in cats with adverse food reactions or inflammatory bowel disease.Dietary options for feline chronic enteropathies

- Highly digestible gastrointestinal diet

- Hydrolysed, ‘hypoallergenic’ diet

- Novel protein diet

Diet may help support the GI tract in a number of ways and while improvements may be documented with a dietary strategy adopted in an individual patient, it may not be possible to determine why that specific diet has had a benefit in that particular case. This is, in part, because of the multifactorial nature of many chronic enteropathies and the multiple potential benefits that diet can have. For example, dietary components such as prebiotics may support the GI microbiota, as dysbiosis is very commonly present in chronic diarrhoea. They may also influence gastrointestinal homeostasis and immune responses. A novel protein or hydrolysed diet containing a reduced antigen content may help minimise adverse food reactions and be helpful both in the diagnosis and management of adverse food reactions. It is important to note that the only way to accurately diagnose an adverse food reaction is an elimination diet trial, as serology testing for food-specific IgE and IgG shows low repeatability and has a highly variable accuracy (Mueller and Olivry, 2017).

Highly digestible, gastrointestinal diets

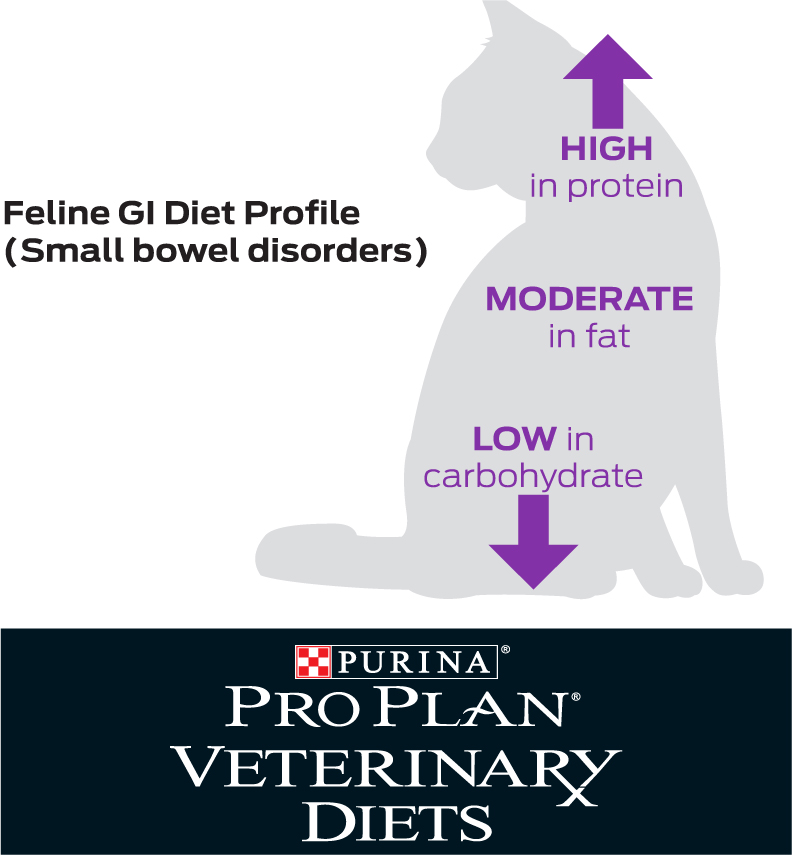

‘Highly digestible’ is not defined in a regulatory sense, but is generally reserved for products with protein digestibility of >87% (typical diets are 78–81%), and fat/carbohydrate digestibility of >90% (typical diets are at least 77–85% and 69–79% respectively) (Zoran, 2008). Highly digestible diets, typically marketed for GI disease, are often selected for acute or chronic diarrhoea cases. There are a range of commercial highly digestible gastrointestinal diets available and they tend to have high palatability, which is important to maximise dietary intake and ensure energy requirements are met. The high digestibility can help reduce exposure to dietary antigens, minimise complications associated with undigested food (such as osmotic diarrhoea or altered microflora) and aid nutrient absorption (Laflamme et al, 2012), particularly in cats with a suboptimal digestive ability. The preferred nutrient profile of highly digestible feline intestinal diets is summarised in Figure 1. Most therapeutic GI diets also incorporate increased levels of omega 3 fatty acids and antioxidants. They tend to be lactose-free, relatively energy dense, and may also incorporate additional ingredients with potential benefits (for example, bentonite, an additive which may help to bind toxins in the GI tract) (Kabak et al, 2006). By their nature, highly digestible, low residue diets contain low levels of insoluble fibres. They should also contain appropriate levels of soluble fibres to help normalise GI motility and provide a source of prebiotics (Figure 2) (Laflamme et al, 2012).

When considering the macronutrient profile of the diet, relatively high protein levels are critical to the health of the GI tract, where they provide energy and promote the natural barrier function of the intestinal mucosa. Protein of a high biological value is beneficial to reducing exposure to ingredients that could cause an adverse food reaction (Laflamme et al, 2012), although it should be remembered that highly digestible diets are not the same as restricted ingredient diets and protein sources do not tend to be limited. The importance of adequate protein in the feline diet and its specific effects on the GI tract were illustrated in a study where cats fed a very low protein diet (20.9% protein) for 10 weeks developed consistently longer villi, deeper crypts and a thicker epithelial cell layer compared to cats fed a more typical dry feline diet (32.7% protein). This was potentially thought to be an adaptive response in the cat's GI tract to increase surface area and maximise protein absorption (Thomas et al, 2008). This is also an example of the role of diet and of specific nutrients in the development of GI disease, not just the management.

Cats have a lower inherent need or ability to digest carbohydrates, and carbohydrate digestion is thought to decrease in cats with chronic enteropathies (Laflamme et al, 2012). Excessive carbohydrate content can be deleterious and lead to osmotic diarrhoea, so restricted levels of highly digestible carbohydrates is desirable for many cats with chronic enteropathy (Laflamme et al, 2012). One study, which was conducted in cats with non-specific chronic diarrhoea, used a highly digestible diet with either low or moderate carbohydrate levels. Improvements in the faecal score of a similar number of cats was found in each group, with a high proportion responding overall but no significant differences in response rate between the two groups (Laflamme et al, 2004). Further work is still needed to determine the optimal level of carbohydrates within the diet for cats with chronic enteropathy.

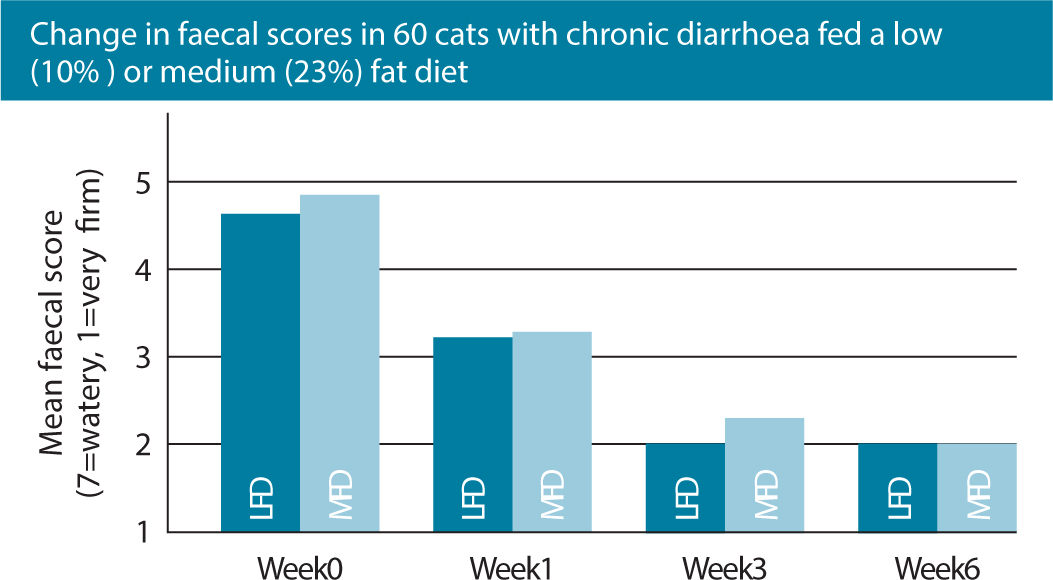

In comparison to dogs, healthy cats are able to digest and use high levels of dietary fat and studies have confirmed that fat restriction may not be beneficial in cats with chronic diarrhoea (Figure 3), with clinical improvement having been documented with and without fat restriction (Laflamme et al, 2011). A highly digestible diet with moderately high fat levels is better adapted to the unique feline digestive physiology, meets the nutritional needs of a cat with debilitating GI disease and can allow reduction in the carbohydrate content of the diet. Higher fat levels also promote palatability, which is critical for acceptance of the food. In one randomised, double-blinded clinical trial evaluating the role of differing dietary fat contents, 55 pet cats with chronic diarrhoea were exclusively fed a highly digestible diet with either a low or medium fat content. Clients recorded faecal scores and the occurrence of vomiting weekly. No significant differences were found between treatment groups, with a high proportion (78%) of cats responding and 36% showing complete normalisation of stool quality. Responses were seen in the first week of treatment, with the maximal responses being seen by 3 weeks and continuing to the end of the study period. See also Figure 3; (Laflamme et al, 2011).

Several studies form the evidence base for use of highly digestible diets. Laflamme et al's (2011) study showed a 78% response rate when cats with chronic diarrhoea were moved to a highly digestible diet. This study provided grade I evidence (the strongest possible evidence) for the potential benefits of dietary intervention with a highly digestible diet in cats with chronic diarrhoea. In a previous study conducted by Laflamme et al (2004), 71% of cats with non-specific chronic diarrhoea showed improvements after being moved to a highly digestible diet, with responses being seen within 1 month. In an additional study of 15 cats, conducted to test the efficacy of two therapeutic diets marketed for cats with diarrhoea, Laflamme et al (2012) demonstrated significant improvements in average faecal score over a 4-week period, with improvements seen in 67% of cats on one of the diets and 40% of cats fed the other diet. Normal stools were achieved in 13.3–46.7% of cats (depending on which of the two diets they were on), confirming the value of dietary change in the management of chronic diarrhoea in cats (Laflamme et al, 2012). Both of the diets used are commercially available in the UK. A recent prospective, multicentre study evaluated the use of two highly digestible feline gastrointestinal dry diets designed to manage non-specific gastrointestinal disorders in 28 cats with a history of chronic vomiting and/or diarrhoea (Perea et al, 2017). This study was conducted over 4 weeks and focused particularly on the impact on vomiting occurence. One of the diets resulted in a significant reduction in vomiting in weeks 2–4 compared to baseline, with a 63% reduction in the final week compared to baseline. This demonstrated that commercially available gastrointestinal formulas can be effective in the management of feline chronic vomiting (Perea et al, 2017).

Novel protein diets

Where there is a strong suspicion that dietary antigens may be a contributor to the chronic enteropathy, novel protein or restricted ingredient diets or a hydrolysed diet may be helpful. Novel protein diets tend to contain a single protein source not found commonly in commercial diets, and a single carbohydrate source. In order to ensure that the protein selected is truly ‘novel’, it is essential that a comprehensive dietary history is taken as there is no single ingredient that will be novel for all individuals. Nutritional assessment forms (Figure 4), such as those freely downloadable from the World Small Animal Veterinary Association Global Nutrition toolkit (https://wsava.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/WSAVA-Global-Nutrition-Toolkit-English.pdf), are a very useful tool to help obtain a detailed diet history. The author also finds requesting photographs of diets or treats fed helpful. However, it can be difficult to fully ascertain all dietary antigens a cat has been exposed to and determine a true novel protein, particularly if that cat goes outside or is fed by multiple people. Dietary antigens most commonly identified in cats include beef, fish and chicken (Mueller et al, 2016), although these results came from surveying cats with cutaneous adverse food reactions so this may not necessarily be reflective of those with GI signs. There are several commercially available novel protein diets that use slightly different ingredients and a home-cooked diet could be trialed as an alternative. However, these should generally only be used short-term, for example, to convince an owner that there may be a dietary element to the chronic diarrhoea, as unless they are formulated by a veterinary nutritionist, these risk nutrient imbalances and are not appropriate for long-term feeding.

One study of 55 cats with chronic idiopathic GI problems demonstrated a clinical response rate of 49% to a commercial selected-protein diet (based on either chicken or venison) as the key treatment intervention (Guilford et al, 2001). This clinical study provided grade III evidence for the role of novel protein diets in management of cats with clinical signs of chronic enteropathy. Of the 55 cats, 29% were diagnosed as food-sensitive (having an underlying food allergy or intolerance), based on a positive response to diet and recurrence of signs upon subsequent challenge with their previous diet. Half of affected cats were found to be sensitive to more than one ingredient. Clinical signs in most food sensitive cats resolved very quickly, within 3–5 days of starting the test diet. An additional 20% of enrolled cats showed resolution of GI signs on the selected protein diet, but no recurrence of clinical signs on subsequent challenge with their original food, suggesting that an aetiology other than food sensitivity resulted in their improvement. The clinical feature most suggestive of food sensitivity was concurrent occurrence of GI and dermatological signs (Guilford et al, 2001). In another study of 23 cats diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease or food-responsive enteropathy, 100% of cats responded to dietary management with an intact selected protein diet fed either alone (in cats with food-responsive enteropathy) or alongside prednisolone (in cats with inflammatory bowel disease) (Jergens et al, 2010). Cats were included in the study if they satisfied the clinical criteria for idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease including persistent (43 weeks) GI signs; had failed to respond to dietary (commercial or intact protein, or hydrolysate elimination diets) or symptomatic (paraciticides, antibiotics, gastrointestinal protectants) therapies alone; had a thorough diagnostic evaluation with exclusion of other causes for gastroenteritis; or had a histologic diagnosis of intestinal inflammation. In all cats with food-responsive enteropathy, diet alone produced a dramatic resolution of clinical signs within 10 days. All cats with inflammatory bowel disease showed clinical resolution of signs within 3 weeks of starting on the diet trial alongside prednisolone. In addition to this, all 23 cats showed significant improvements in the feline chronic enteropathy activity index, defined as a combination of gastrointestinal signs, endoscopic abnormalities, serum total protein, serum alanine transaminase/alkaline phosphatase activity and serum phosphorus concentrations (Jergens et al, 2010). This study showed the critical role dietary management can play in feline chronic enteropathy either alone or as an adjunct to other therapies.

Hydrolysed diets

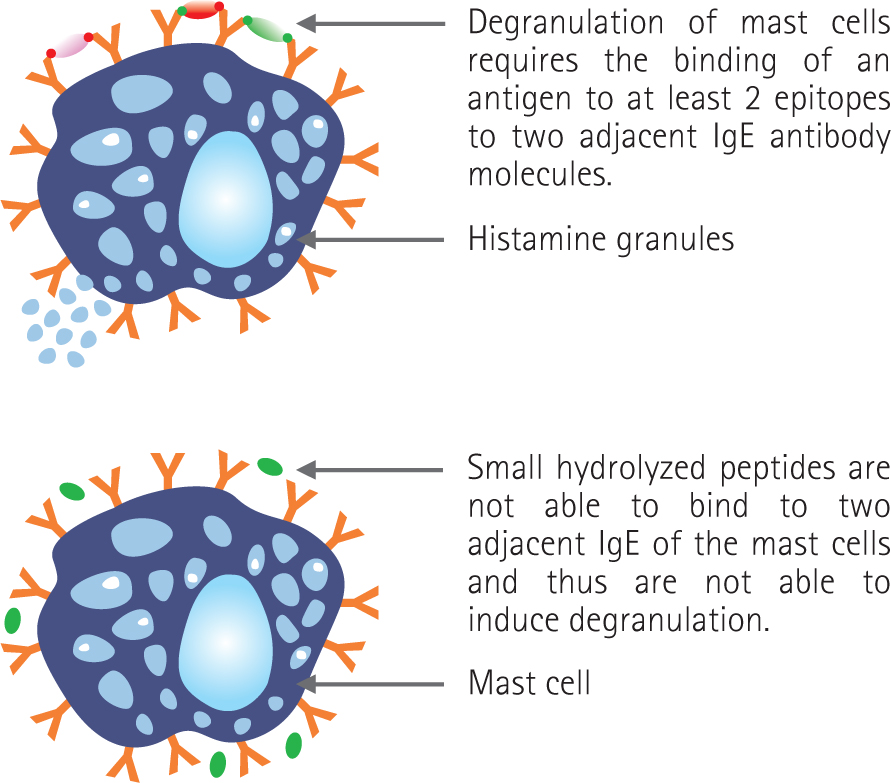

Hydrolysed diets are based on protein sources that have been enzymatically cleaved to a very small size, reducing their molecular weight to below that needed to stimulate an immune response (Figure 5). Alongside protein size, parameters such as the number and location of epitopes and the protein source can also be important in influencing the true ‘hypoallergenicity’ of a diet (Cave, 2006). Hydrolysis should ideally sufficiently disrupt the protein structure within the diet to remove any existing allergens and allergenic epitopes, thereby preventing immune recognition in animals sensitised to the intact protein. They can be particularly helpful where it is difficult to ascertain a novel protein for a patient, although a recent large-scale review of the current evidence for dietary management of GI signs in cats concluded that it is not possible to ascertain whether a novel protein or hydrolysed diet is likely to be most effective (Makielski et al, 2019). Hydrolysed diets tend to have high digestibility and often contain increased omega 3 fatty acids, which can reduce excessive inflammation and may be helpful in patients with chronic enteropathy (Laflamme et al, 2012). However, one disadvantage of them is that the hydrolysis process can make proteins unpalatable. When a protein is hydrolysed, the peptide fragments that contain hydrophobic side chains are exposed and can be tasted. Thus, as hydrolysis proceeds, bitterness tends to increase (Cave, 2006). This can result in a poor acceptance in some patients. There are several commercially available, fully hydrolysed diets using different protein sources and with varying palatability, so if refusal is met in one patient it can be worthwhile trialling with an alternative.

Grade I evidence for the use of hydrolysed diets in feline chronic enteropathy has been provided by a small-scale randomised controlled trial, in which the efficacy of a hydrolysed soya diet was assessed in 10 cats with chronic enteropathies (Waly et al, 2010). Cats were fed either a hydrolysed soya protein diet or a therapeutic intestinal diet, over a 4-week period. The resolution of GI signs was observed in 70% of cats fed the hydrolysed diet, versus 30% of cats fed the intestinal diet. Different clinical responses to dietary intervention were observed and the effect of the hydrolysed diet compared to the intestinal diet was not statistically different, although this observation may have been influenced by the small number of cats enrolled in the trial (Waly et al, 2010). Another small-scale study in eight cats diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease or adverse food reactions documented resolution of clinical signs in all eight cats within 4–8 days when switched to a hydrolysed diet (Mandigers et al, 2010). Challenge with their previous diet resulted in recurrence of the clinical signs and the authors concluded that the hydrolysed diet was effective to manage these cats (Mandigers et al, 2010). A recent, larger-scale study also provided support for the use of hydrolysed diets in cats with chronic vomiting and/or diarrhoea (Kathrani et al, 2020). This evaluated the responses of 977 cats prescribed a hydrolysed diet, with or without concurrent medication (antibiotic and/or glucocorticoids) for chronic vomiting and/or diarrhoea of undetermined aetiology, by analysing records of cats in primary care practice. The level of poor response, rather than positive response, was measured. A poor response was defined as evidence of receiving antibiotic or glucocorticoid treatment for vomiting or diarrhoea at visits, after the hydrolysed diet was started, or death from GI signs, within the follow-up period (which was a minimum of 6 months). Of the cats studied, 71% were first prescribed the diet without concurrent antibiotics or glucocorticoids, while 29% first received the diet with these medications. A poor response was seen in 42% of cats within the follow-up period. Cats aged over 6 years and cats prescribed antibiotic and/or glucocorticoid for vomiting/diarrhoea before and during the diet had higher odds of a poor response. This may have reflected the severity of their disease, although it could also have resulted from the effects of antibiotics on the intestinal microbiota and subsequent intestinal dysbiosis, and/or a dampening of the immune system by glucocorticoids, affecting response to a hydrolysed diet. The findings of this study suggested there is value to trialling a hydrolysed diet first as a monotherapy in cats with chronic vomiting/diarrhoea, when diagnostic investigations do not reveal a cause, before resorting to antibiotic and/or glucocorticoid therapy (Kathrani et al, 2020).

Diet choice and introduction

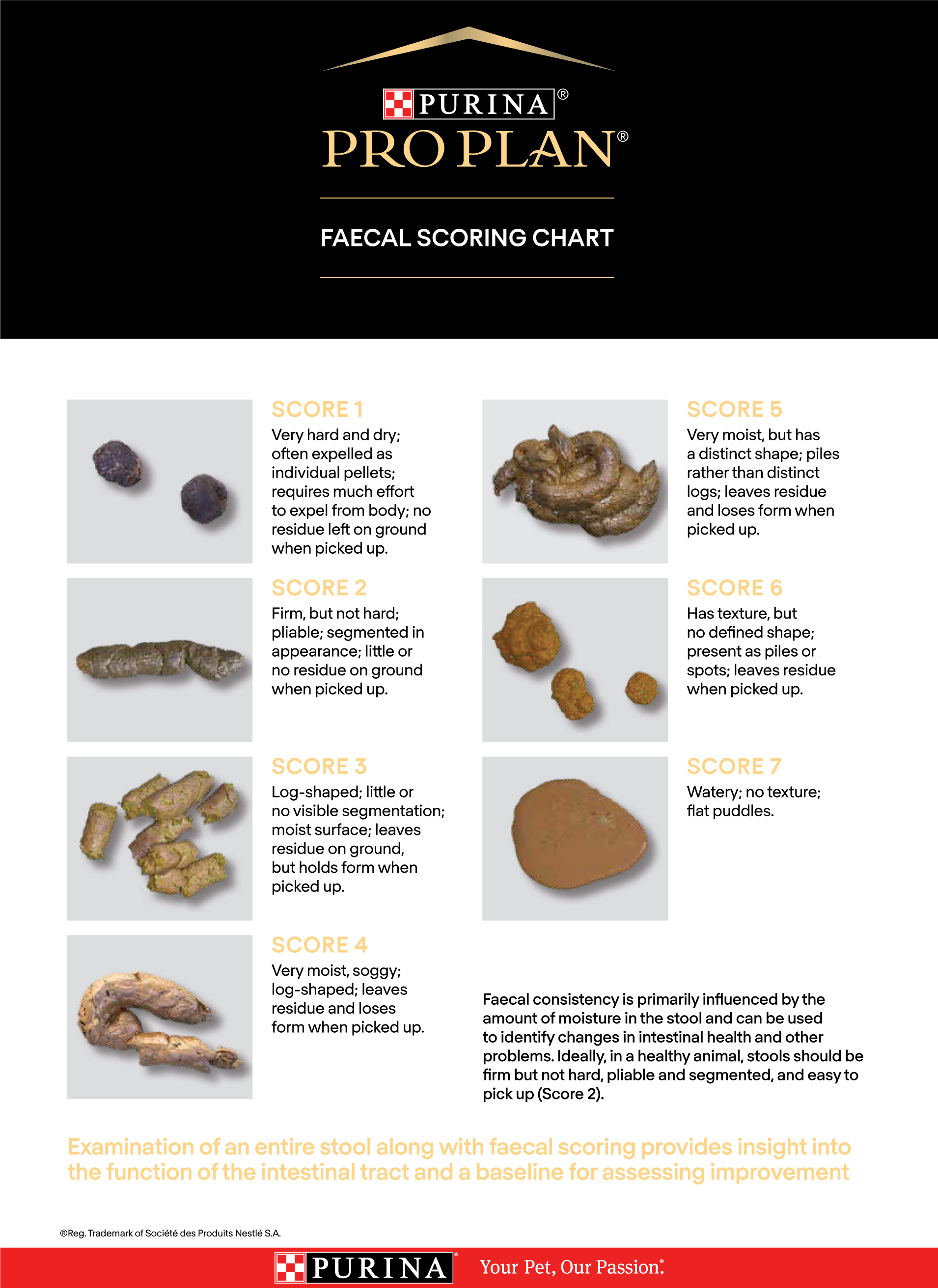

Obtaining a good diet history can help identify a novel protein source, as well as any food preferences (flavours or textures), and may guide the choice between a highly digestible, hydrolysed or novel protein diet. Many commercially available diets come in a range of textures and different brands offer different flavours, so consideration of more than one brand may help maximise the likelihood of acceptance. If conducting an elimination diet trial, a restricted ingredient (novel protein or hydrolysed) diet should be used first. Studies have documented improvements in clinical signs rapidly after starting appropriate dietary management, so letting owners know that improvements should be seen within 2 weeks may encourage them to trial the diet. Providing a faecal scoring chart (Figure 6) and encouraging owners to document clinical signs before and after starting the diet trial may also help ascertain whether improvements are seen. If improvements have not been seen within 2 weeks, providing there has been compliance, moving onto a diet in a different category is generally recommended, particularly since individuals may respond differently to diets within different categories. Preparing owners for the possibility of trialling multiple diets, as well as emphasising the importance of compliance during the trials, can be helpful. Where an elimination diet trial is being conducted, ensuring all members of the household are aware of the importance of feeding the cat only with the diet provided and ensuring it does not have access to other cat foods, treats or other extras is critical. Cats should be kept in during the elimination diet trial to minimise the risk of hunting or obtaining food elsewhere, although for some owners and cats this may not be a realistic option.

Ideally, small amounts of the diet should be offered frequently, in at least 3–4 meals daily. The larger the meal size in a cat with GI disease, the more likely the food will be vomited or expelled in diarrhoea because of inefficient digestion or absorption. Cats also have a relatively less distensible stomach and are more adapted to small, frequent meals rather than larger meals offered once or twice daily. Ensuring the diet is introduced in a quiet, non-stressful area of the home, with any nausea being adequately treated before diet introduction, is important. Additionally, if any medications are being administered they should be given separately to the meal to minimise the risk of a food aversion developing. Care should be taken to ensure medications do not contain proteins that could potentially interfere with any elimination diet trial.

Other considerations

Serum cobalamin levels should be measured in cats with chronic enteropathy. This can often be deficient, particularly as cats are thought to be very susceptible to cobalamin deficiency. This was documented in over 60% of cats with signs of GI disease in one study by Simpson et al (2001). Cobalamin is critical for GI cell repair and normal GI function. Without supplementation (either orally or parentally), cobalamin deficiencies may inhibit improvements in clinical signs even if an appropriate diet has been started (Toresson et al, 2017).

The use of probiotics may also be considered in order to support any dysbiosis present, which is a common finding in cats with chronic enteropathy, although generally their use should be considered as an adjunct to other management strategies rather than being used alone. Some probiotics have been shown to be helpful in some cats with chronic diarrhoea. For example, in one study, a multi-strain synbiotic administered to cats with chronic diarrhoea resulted in improvements in mean fecal score based on a standardised scoring system, with 72% owners perceiving an improvement in their cat's diarrhoea after a 21-day course of synbiotic supplementation (Hart et al, 2012). However, there was no control group in this study. There is great variability in the quality and potential efficacy of veterinary-authorised probiotic products and not all studies document improvements. Clinicians are encouraged to assess the evidence for the particular strain and preparation of probiotic being marketed, before selecting it for use.

Conclusions

Pharmaceutical agents are often given inappropriate precedence in the treatment of gastrointestinal tract diseases. However, nutrition can have significant influences on the GI tract and dietary intervention should be central to the management strategy in many cats with chronic enteropathy, either alone or alongside medications. A diet trial is appropriate for many cats with chronic enteropathies and may be considered relatively early in the diagnostic investigation in otherwise clinically stable and younger cats. However, there is still a lack of evidence to determine whether a highly digestible, hydrolysed or novel protein diet is the most likely to result in a positive response, or which diet(s) may be most successful in which circumstances. In some cases, more than one diet may need to be trialled before improvements are seen. However, given the high response rate of cats with chronic enteropathy to diet manipulation, discussion of dietary management and use of diet as a diagnostic and/or therapeutic tool should form part of the management plan for any feline patient with chronic enteropathy.

KEY POINTS

- A high proportion of cats with a chronic enteropathy presenting with chronic diarrhoea will benefit from nutritional support

- Dietary management can be considered a key diagnostic tool and a diet trial should be considered early on in the investigation process in otherwise stable cats

- Three main dietary approaches exist: highly digestible diets, hydrolysed diets and novel protein or selected ingredient diets

- Where a food allergy or intolerance is suspected, a hydrolysed or novel protein diet should be selected for the diet trial initially

- Clinical improvements should be seen rapidly if an individual patient is going to respond to a particular dietary strategy, with resolution of clinical signs often possible within 2 weeks

- Nutritional intervention, either alone or alongside other management strategies including the use of medications, cobalamin supplementation or probiotics, is key to optimising long-term management of cats with chronic enteropathy.