This roundtable, held 16 January 2020, was sponsored by Bayer. The aim was to inform and guide discussions with pet owners regarding Angiostrongylus vasorum and other lungworms, and enable veterinary practices to provide appropriate preventative and treatment advice and care.

Factors driving Angiostrongylus vasorum distribution and canine exposure risk — Eric Morgan

Angiostrongylus vasorum has been found with increasing frequency in the UK and across Europe, posing a growing threat to domestic dogs.

Previously, A. vasorum was regarded as confined to small pockets in West Cornwall (Truro area) and South Wales (Swansea area). However, by 2000 reports suggested that it had become established in south-east England. It has since been recorded in dogs in the Midlands and as far north as Glasgow, so that now it is perceived as a potential threat to domestic dogs throughout the UK mainland. But has this rapid spread been a real change, or is it an artefact caused by increased awareness of the parasite's biology, together with the availability of new tests?

The traditional Baermann technique for detecting larval and adult worms in faecal samples is an unpopular chore for laboratory staff and lacks sensitivity. It is likely to provide false negative results, particularly in practices unused to carrying out the test. A survey in 2016 using the new ELISA-based tests demonstrated that worm antigen was present in 1.3% of 4000 canine samples from around the UK and 3.2% of the dogs had seroconverted (Schnyder et al, 2013). Mass screenings using ELISA have demonstrated that the parasite's range extends into other countries across Europe where there have been no confirmed clinical cases in dogs, such as Portugal, Greece, Romania and Turkey.

There are deficiencies in the available UK data on the prevalence and clinical significance of A. vasorum in the dog population. The distribution appears patchy and there is no data from several counties. Attempts to encourage practitioners throughout the country to log positive tests have produced disappointing results.

In the absence of reliable information from dogs, post-mortem samples from the main wildlife host (fox) provide useful data. Samples examined confirm that there is an increasing prevalence of A. vasorum in foxes (e.g. in the south-east from 23% in 2005–06 to >50% by 2013–14), and between surveys carried out in 2005–06 and 2013–14 there was an expansion in its range, with areas that had been free now colonised.

The increasing prevalence of lungworm in foxes in Britain reflects a trend seen in other countries. For example, Switzerland has seen the numbers of A. vasorum positive samples from foxes in Zurich increase from 10% 10 years ago to 75% in recent years. There are clearly changes in the prevalence of this parasite, unrelated to awareness and the number of tests being carried out on dogs in veterinary practices.

Examination of A. vasorum from foxes and dogs has demonstrated a high level of genetic diversity, but no evidence of different strains in the two species. Evidence of a geographical gradient in the genetic diversity (15 haplotypes in the south east, only one further north — one that is quite common further south) provides further support for the view of recent UK south to north spread.

The parasite will not be constrained from spreading by lack of either definitive or intermediate hosts. Foxes have long been ubiquitous throughout the country and there have been no observable changes in the distribution of the slugs that serve as intermediate hosts.

Required conditions (based on models) include an average winter temperature above -4°C and moist, mild summer conditions. A global distribution map of suitable environments developed using these criteria correlated well with known areas of A. vasorum distribution and highlighted potential area for future colonisation. This model agrees with the distribution of the parasite in Europe but does not explain the northwards expansion in the UK, as these conditions are (and have been) already present across the UK.

In Great Britain, the parasite appears to be widely distributed but not in great numbers. Practitioners may report having seen A. vasorum in a patient, but fewer clinics outside the south east of England and southwest Wales are regularly seeing cases. It seems likely that this patchy distribution is a normal process in which localised hot spots emerge slowly and coalesce together over time as the parasite becomes established in the local host population. In the Irish Republic, the parasite is already found in foxes in all 26 counties and the prevalence is predicted to increase.

Fox movements may drive localised changes in parasite distribution but the long-distance spread seen is more likely to be associated with increased movements of dogs around the country. If the climate favours transmission of the parasite, then introduction associated with dog movements may become more likely. The relative contribution of foxes and dogs to the spread of A. vasorum is difficult to gauge. Prevalence of infection may be higher in foxes than in dogs, but the much higher density of dogs in urban centres means that dogs might be responsible for more environmental contamination, as has been shown for Toxocara spp. However, once it is circulating in the fox population, even 100% treatment in dogs will not eliminate the parasite from an area.

Iain Peters suggested that second homes may have been a factor in the rapid colonisation by A. vasorum of north Gloucestershire, an area popular with people who spend their working week in London. Ian Wright added that his clients regularly blame the emergence of lungworm in northern England on dogs travelling to the UK from abroad but there is little evidence to support this.

Slugs are probably much more important than snails as intermediate hosts (IH). Many species of both mollusc groups have been shown to be capable of acting as IH, but they are not equally effective. Many slug species are voracious feeders on mammalian faeces and UK snails are not. Unlike most snail species, which may live several years, slugs only live for a few months (larger slug species hatch February, breed August–September, and die) but they will be active in the autumn months when the risk of transmission to dogs appears to be at its peak. In the UK, transmission may occur year-round, but the risk is greatly reduced in colder winters.

The greatest risk is through ingesting live infected slugs. The larger slug species have effective defences: they have tough skin, can cling tightly to a solid surface, will release mucus when disturbed, are unpleasant tasting and can even make hissing noises. Some dogs may actively seek out and eat slugs, but it is probable that most are ingested accidentally, particularly smaller slugs, when chewing or licking grass. It is doubtful that the parasite could be transmitted to dogs by licking slug or snail trails, but dog owners should be made aware of the risk that their pet might ingest the parasite when drinking from puddles contaminated with worm larvae released from dead or dying slugs.

Hany Elsheikha wondered whether it mattered whether live or dead slugs were eaten by dogs? Eric Morgan said it wasn't known whether that would have an effect. Ian Wright added that some dogs will eat anything, slugs (live or dead) included.

Previously, only the smaller slug species were active all year round, with larger species not being found during the winter. However, the risk of all year-round exposure to slugs may increase, and is probably already increasing, as a result of climate change and milder winters. Snails will move to seek preferred microclimates and avoid extreme heat, cold and dryness. In the garden environment, any slug species may keep active in warm microhabitats such as compost heaps. Citizen science could assist in finding out more about slugs and snails in the garden enviornment.

Snails infected with Angiostrongylus sp. have been found to prefer cooler environments. It is possible (but unknown) that this is an adaptation to slow the parasite's growth rate.

There is insufficient evidence to say whether the population of slugs in the UK is increasing, and whether this could be a factor in the spread of A. vasorum, but slug numbers may be increasing. In general, snails are more common in the east of Great Britain and slugs in the west, which is related to soil type and calcium availability. There is still much unknown about slug biology.

Other mammals can also act as hosts: red pandas in British zoos have been confirmed as hosts, also stoats, weasels and meerkats. Molecular studies on A. vasorum taken from canid species from North and South America indicate that the relationship between parasite and host is long-standing and the two have co-evolved. But that does not mean that the parasite is benign in foxes; there is evidence of pathological changes to the cardiac tissues of some wildlife hosts.

Jenny Helm noted that Danish researchers have produced evidence of less acute haemorrhagic disease and more chronic signs in dogs, which may indicate greater tolerance between parasite and host. Eric Morgan's experience in the Swansea area where the parasite is long-established, was that dogs invariably showed respiratory signs rather than bleeding disorders. Little is known about the factors that trigger haemorrhagic conditions in some patients: level of infection, dog genetics, pre-exposure?

Jenny Helm noted that there may be more dogs with coagulopathies than indicated by those with external clinical signs of bleeding. Clinicians are more likely to identify problems when they are actively looking for them. It is now more widely known that lungworm can cause coagulopathies and so this will be among the differential diagnoses proposed when such cases are presented at a referral clinic. Kit Sturgess added that cases of unexplained bleeding are more likely to be referred than patients with respiratory signs — and more likely to be written up. Andy Torrance proposed that parasites living in the pulmonary artery will tend to be adapted to avoid attracting platelets and coagulation factors, by modifying the host's coagulation response. In foxes, this strategy may be finely tuned to avoid damaging the host. But in dogs, as more recent hosts, the process may have more wide-ranging effects that can provoke a fatal coagulopathy. He felt that there is some published evidence to support this theory and it would be a fascinating area for future studies. Jenny Helm agreed, suggesting that these anti-coagulation properties could be a promising area for the development of new therapies, including potential drugs to replace warfarin.

Kit Sturgess noted that most infectious pathogens only cause minor clinical signs in an otherwise healthy animal. It will usually require the introduction of another factor to induce serious disease signs. The problem is that we do not always know what these trigger factors are. Control involves avoiding ingestion and/or use of anthelmintics. Owners should try to prevent their dog eating slugs, but using poisons to eradicate slugs from gardens is not recommended. Indeed, molluscicides may make dogs more likely to ingest slugs, as dead slugs are more likely to be found in the open than live ones (and such products can be dangerous to other garden residents).

A dog's exposure can be minimised through knowledge of slug biology. Slugs are most active after dusk, and their morning activity is dependent on night-time minimum temperatures rather than light intensity. So keeping dogs on leads and restricting their ability to lick or eat vegetation or slugs at these times should reduce exposure risk.

Regular anthelmintic treatment of dogs throughout the country, not just in those areas where there is a high prevalence, may slow down further expansion.

Key points

- Just because you don't think you see much lungworm now, it does not mean that this situation is stable.

- The parasite is spreading into new areas and the first you will know about it is when cases appear.

- Cases can be difficult to recognise and to diagnose, and are sometimes severe, so remain vigilant.

- Movement of dogs (vacations, moving house, or to and from second homes), has probably driven long-distance spread of lungworm in the UK.

- Mild, humid weather that may occur with climate change will tend to favour slug activity and year-round breeding, increasing opportunities for infection.

- Incidental ingestion of small slugs on grass, and potentially larvae from puddles, may be the major sources for dogs, rather than consumption of large slugs/snails.

Clinical presentation of A. vasorum infections — Jenny Helm

The clinical picture in canine lungworm cases may be highly variable. So first opinion practitioners will need to be alert for those cases that present with the more unusual signs.

Cases of A. vasorum infection can be extremely varied in presentation, ranging from dogs that are largely asymptomatic to those with respiratory signs to those dying from severe coagulopathies. The difference between these extremes is likely due to some component of the host's immune response or parasite/host interaction. Where the disease is more common, clinicians are more likely to see cases with more unusual presentations, such as neurological signs, and are more likely to consider A. vasorum infection in the differential diagnoses. The dog that became the index case for A. vasorum in the Glasgow region presented with haemorrhagic sclera and a haematoma over its thorax. However, most dogs with this parasite will present with cardiorespiratory signs (coughing in about 70%, dyspnoea in 23% in one study (Koch et al, 2005)). Other common signs include haemorrhage (e.g. epistaxis, conjunctival bleeding, prolonged surgical bleeding)(15.6%), neurological signs, lethargy (15.6%), anorexia (14.4%) and weight loss (11.35%), while 6.9% were asymptomatic in the Koch et al (2005) study. Most neurological presentations are probably the result of haemorrhages within the central nervous system; occasionally aberrant larval migrans may be responsible. Larvae may also enter other body sytems — eyes, skin (associated dermatitis has been noted), sinuses and others.

These various cardiorespiratory, coagulopathic, neurological and non-specific signs are not mutually exclusive; some patients may have a combination of these. Atypical presentations are more likely to be written up, so cases appear in the literature involving haemoabdomen and haemothorax, gastric dilatation (probably aerophagia due to respiratory problems), pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale, etc. (Kit Sturgess had seen pain as a presentation, due to sub-muscular haemorrhage tearing muscle off the periosteum). However, while lungworm should be considered, it is important to remember that for many of these signs, other causes are more common.

Even if asymptomatic (6.9% in Koch et al, 2005), A. vasorum infection may place the patient at increased risk of perior postoperative haemorrhage. It may therefore be prudent to test those patients with suspicious signs before carrying out a surgical procedure. However, testing too early (e.g. 2–3 weeks before) may miss cases, due to the prepatent period Robyn Farquhar agreed that a presurgical Angio Detect (IDEXX) ELISA test for A. vasorum was a worthwhile precaution. This test is routinely offered to owners of patients undergoing surgery at her practice unless the animal has been regularly treated with a moxidectin spot-on. Kit Sturgess cautioned that there is a risk of false positive results in any test, and in low prevalence areas using the available technologies may result in a skewing of the prevalence data. Jenny Helm agreed regarding using such results for epidemiological data.

Andy Torrance had been questioned on the most appropriate pre-surgical test: the A. vasorum antigen assay or testing buccal mucosa bleeding time (BMBT). He concluded that it was probably the latter. Kit Sturgess was less sure, due to inter-operator variation with the BMBT. He suggested a thromboelastometry test would be useful and detect a broader range of bleeding problems. Jenny Helm felt that the BMBT is difficult to perform reliably in conscious dogs and an Angio Detect test was good practice; the only problem with false positives would be a delay in the surgery to carry out further diagnostics or lungworm treatment.

Robyn Farquhar felt that the BMBT was less practical and should be used only in highrisk situations. After treating two cases with A. vasorum-related coagulopathy, her staff were alert to the problem and found it easy to persuade clients that Angio Detect was a sensible precaution before surgery. Eric Morgan would be concerned about the possibility of false negatives, although Kit Sturgess noted they would be very uncommon in a low-prevalence population. Jenny Helm suggested that more should be done to use data from first opinion practices.

Various hypotheses have been suggested for the hypocoagulability associated with A. vasorum infection, including DIC associated with anti-platelet antibodies, parasite antigens/proteins or endothelial disruption. Other suggestions include acquired von Willebrand factor deficiency, or decrease in blood factors V and VIII, although normal blood coagulation times and normal platelets also occur in affected patients.

The approach to coagulopathies has changed markedly in recent years, with new scientific and technical developments. A Petsavers study (Adamantos et al, 2015) used thromboelastography (TEG) and in 73% of study dogs there was evidence of a hypocoagulable state, even in dogs with no evidence of bleeding. This study suggested a disorder of primary haemostasis, but, other studies on naturally-infected dogs (Sigrist et al, 2017; Cole et al, 2018) indicate failings in tertiary haemostasis (reduced clot stability, with hyperfibrinolysis and hypofibrinogenaemia being common findings). This has also led to changes in treatment, suggesting that plasma may be useful, as well as tranexamic acid.

Kit Sturgess observed that tranexamic acid, although classed as an anti-fibrinolytic drug, seems to have broader activity to prevent bleeding, and has been used in situations where coagulopathy was not present, e.g. epistaxis secondary to neoplasia. Jenny Helm agreed that the methods by which tranexamic acid worked were not yet fully understood. She predicted that if TEG tests become available for use in practice, they would probably become the most useful preoperative bleeding test.

Regarding diagnostic imaging, thoracic radiographs have been used for many years in assessing patients with A. vasorum infection. This would be looking mainly for evidence of diffuse bronchial thickening with an interstitial lung pattern, focal (often peripheral) alveolar infiltrates and, later on, a predominantly patchy alveolar pattern. A study using thoracic computed tomography (CT) also revealed a mixed alveolar interstitial pattern but with no relationship between CT severity score and clinical outcomes (Coia et al, 2017). All dogs had pleural and subpleural changes. Nodules may be seen, which could cause suspicion of neoplasia. Treatment to kill lungworms will result in inflammatory changes, which will resolve slowly. Further imaging studies may be needed to follow the process. It would be interesting to have better information on what happens to the dead larvae following treatment: coughed up and swallowed or coughed out in sputum, degraded etc. Hany Elsheikha thought it was probably a combination of these.

There have been suggestions in the literature that certain breeds are more susceptible to lungworm infection: Staffordshire Bull Terriers, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels and Cocker Spaniels. There is no firm evidence to support this. Kit Sturgess's experience had been that Boxers with lungworm did badly, possibly associated with breed-associated immune response. He also wondered if age of exposure was relevant to the clinical outcomes, with those infected at an early age having less severe disease than those exposed at an older age. Eric Morgan noted that there seems to be an interaction between age of presenting dogs and geographical area (older dogs presenting in areas where spread is more recent). Ian Wright mentioned that the parasitologist Mark Fox had noted that in the south west the early cases of lungworm had presented mainly with respiratory signs and coagulopathy, but over time, cases with neurological signs became more frequent — possibly a change in reporting.

Eric Morgan had noted a correlation between worm burden and clinical signs: dogs with heavy burdens (many larvae on Baermann's) were much more likely to have had clinical signs noted by the presenting vet. Those with few larvae were asymptomatic. Eric Morgan noted that we don't know if any larvae become arrested and later (after treatment has killed developed worms) start to develop. Kit Sturgess wondered whether global epidemiological findings had been influenced by where there was routine prophylaxis against Dirofilaria. Jenny Helm agreed: lungworm is not a large problem in North America, where heartworm prevention is routine. Eric Morgan noted than monthly treatment did not prevent initial infection and exposure to antigens, but affected patency and prolonged exposure.

Jenny Helm would like a major prospective study on A. vasorum exposure in the dog population nationwide. Eric Morgan noted that a study linking all the UK vet school diagnostic labs had been proposed but had been unable to secure funding. A large study would be needed, to address the confounding factors and capture the variation in anthelmintic treatment across the dog population.

Eric Morgan thought there could be a link in which owners contributed data from their pet and received more information online at the same time. Robyn Farquhar felt that practitioners were far more likely to engage if they have had a recent case or if the condition concerned is difficult to treat. There is a feeling among colleagues that lungworm is easily controlled using the available anthelmintic treatments. Ian Wright felt there was a growing reluctance among clients to seek routine treatment for parasitic diseases, due to concerns over the environmental impact of drug residues. Studies coming from independent organisations are important to show that the findings are not being driven by commercial interests. There is an urgent need for meaningful, large-scale data on parasite control at a national level. Within ESCCAP there have been discussions on whether control effort should focus on testing for the worm or on routine preventive treatment — but many dogs in the UK receive neither.

Key points

- The clinical presentation of Angiostrongylus vasorum infection is wide and varied, so it should be considered as a differential diagnosis in a wide range of cases. However, it is obviously important not to miss other, more common, differentials.

- Make sure Angiostrongylus vasorum remains on a differential list even if prophylaxis appears to have been adhered to diligently.

- Progress in understanding the aetiopathogenesis of coagulopathies in dogs with A. vasorum infection has led to the recommendation of tranexamic acid treatment in some cases, also plasma transfusions.

Current and future diagnostic testing for A. vasorum — Andrew Torrance

Choosing the right diagnostic techniques can save time and effort in dealing with cases presenting at veterinary practices in areas previously believed to be A. vasorum-free.

Andy Torrance described a case that highlighted many of the challenges in diagnosis. A 2-year-old French Bulldog had a 2-day history of bleeding from a laceration above a premolar; the dog had a coagulopathy but no other obvious clinical signs. Blood was positive for Angiostrongylus antigen and it was Angiostrongylus qPCR positive, but negative on faecal smear and Baermann's for strongyl larvae. Coagulopathy appeared to have developed in the pre-patent period.

As suggested earlier, the worm appears to be interacting with its host at a fundamental homeostatic level, which helps to explain some of the wide-ranging biological effects that are still not well understood. In the pre-patent phase, when adult worms first enter the pulmonary artery, those interactions will be the source of the coagulopathic, and possibly also the cardiac, signs seen in some patients. Later, a patent infection may result in other clinical features of this condition, including associated with larval migration. Some patients will show a mixture of the presentations.

Diagnosing infection in the pre-patent phase may be challenging. The antigen ELISA (Angio Detect) is commercially available. Antibody-ELISA tests may perform well in a laboratory setting, but have not been developed for commercial use. There are opportunities for anyone who can produce a suitable antibody test for use in first opinion veterinary practice.

For patent infections, both the faecal smear and Baermann's techniques may be carried out in a practice laboratory, but they will only characterise positive samples as strongyle larvae. To confirm using microscopy, clinicians would need to highly skilled at spotting the features distinguishing Angiostrongylus spp. from other strongyl larvae with very similar morphology, especially when coiled up. (Hany Elsheikha noted that for live, unstained parasites in a wetprep, chilling the sample leads to larvae uncoiling, allowing easier identification.) Antigen ELISA (Angio Detect) and antibody ELISA are species-specific, as is qPCR.

Antigen ELISAs and Angio Detect will detect adult excretory/secretory antigen with reasonable accuracy (sensitivity 85–97% and 94–100% specificity). Infection will become detectable at 7–11 weeks post infection and go negative from 3–7 weeks after effective anthelmintic treatment. Antibody ELISAs have sensitivity 85–86% and specificity 98–99%. These become positive by 3–6 weeks post infection and go negative from 3-9 weeks after treatment. It is important to choose a test which will effectively detect both the presence of the parasite and the success of treatment.

The qPCR test detects the spacer region on the ribosomal gene that is expressed consistently in this group of parasites, and will detect the presence of worm DNA with great precision (sensititivity is 97–100%, specificity 98-100%). In blood it may detect the parasite at 2–10 weeks post infection (i.e. starting earlier than any other test), but intermittently. qPCR on faeces and broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) examination will detect patent infection from 7–8 weeks post infection and become negative 2–3 weeks after treatment. (Jenny Helm noted that BAL may be positive before faeces). The faecal smear test has poor specificity and sensitivity of only 61%, which is be unacceptably low for diagnostic purposes.

Iain Peters explained that the most common application of qPCR in a diagnostic laboratory is in testing BAL samples (or faecal samples) to determine the species of larvae found — usually A. vasorum or the less pathogenic species Crenosoma vulpis. Rarely, other species may also be present, particularly (and sometimes in large numbers) in samples from immunosuppressed dogs.

A paper by Cannone et al (2018) compared the accuracy of different diagnostic methods in seven dogs with a cough, exercise intolerance and dyspnoea. Positive results were: Baermann's 3/7, Angio Detect 2/7, ELISA circulating antigen 3/6, ELISA for circulating specific antibodies 6/6, qPCR test on BAL 7/7, suggesting the antibody ELISA and qPCR on BAL should be used on suspicious cases negative with other methods. However, the study did only involve seven cases. A summary of test order preference (most likely to be useful first) is given in Table 1.

Table 1. Suggested order of preference for tests

| Situation | Tests |

|---|---|

| Pre-patent infections, screening dogs with cardiac signs, unexplained coagulopathies and thrombocytopathies | antibody ELISA > Angio Detect and antigen ELISA > blood qPCR > Faecal or broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) qPCR > (Baermann's > faecal smears would not be suitable) |

| Patent infections with cardiac signs, unexplained bleeding and/or respiratory signs | BAL qPCR or ELISA for antibodies > Angio Detect or antigen ELISAs or faecal qPCR > Baermann's > faecal smears. (Blood qPCR would not be suitable) |

| To assess clearance of infection post treatment | BAL qPCR (but invasive) > faecal qPCR > Baermann's > Angio Detect and antigen ELISAs > ELISA for antibodies. (Neither blood qPCR nor faecal smears suitable) |

| Identification/differentiation of larvae | qPCR on BAL or faeces > cytological examination |

There was considerable discussion regarding antigen and antibody tests. It was agreed that if a combined antigen and antibody rapid test became available, that would be very useful.

Ian Wright noted that despite its lack of sensitivity, the faecal smear has the advantage of being cheap and easy to perform. It is important to remember that a negative result gives zero information, but a positive finding offers immediate clinical value because the specificity is good. Furthermore, the ability of suitably trained first opinion vets and VNs to detect larvae can match that of specialist parasitologists. Robyn Farquhar and Jenny Helm agreed. Iain Peters reiterated that qPCR had found 2/3 of larvae in cases to be Angiostrongylus and 1/3 Crenosoma. Eric Morgan added that samples had to be collected correctly (e.g. direct rectal sample, not faeces from grass). He added that a low-sensitivity test widely applied combined with a high-sensitivity test used rarely was better than either alone. Andy Torrance agreed that in-house labs kept people interested, which was a good thing, but it was important to recognise the limitations. Iain Peters said that whether in-house or specialist laboratory testing was appropriate depends on the reasons for testing. It is a different issue screening a healthy pet as a pre-surgical precaution, compared with a seriously sick animal requiring a reliable diagnosis. Ian pointed out that for e.g. the ‘coughing’ dog, a basic smear to possibly detect Angiostrongylus was better than the practical alternative of no testing. There was general agreement: and that for a sick animal, professional laboratory testing was preferable (but a rapid in-house test initially is useful).

Ian Wright felt there were occasions when first opinion practitioners may fail to fully understand how testing works and what sensitivity and specificity mean in practice. There is a need for more CPD on this. Kit Sturgess noted that busy practitioners really want a 100% sensitive, 100% specific test, which doesn't exist. It also takes time for a new test or treatment to become commonly used. Robyn Farquhar noted that practices see a hugh diversity of cases, so any test that can be done simply, quickly and preferably noninvasively is a bonus. Cost is also a significant factor. Jenny Helm added that she would definitely use a bedside PCR on faeces if it was available and not too expensive. Ian Wright noted again that the smear is still a useful initial screen, and that was agreed. Kit Sturgess noted that test acceptance increased once they became part of a routine screening panel (e.g. T4 on geriatric cat screen, detecting hyperthyroid cats). Getting Angiostrongylus included in a ‘coughing dog profile’ would be great! Technical/practical problems with setting this up were discussed.

Regarding surveillance, Andy Torrance acknowledged that, like practices, commercial laboratories are extremely busy and have little time to conduct the sort of work that would provide useful information. Initiatives such as SAVSNET are important developments in using the information available from practices and labs, but there is much more still to be done in harvesting this data. Debra Bourne wondered whether student projects could be useful; the problem is breaking down the study to create something achievable in the limited time they would have available. Kit Sturgess warned that the time needed for a senior vet to manage student projects could be considerable. Hany Elsheikha noted that is the role of academic institutions. Jenny Helm noted the difficulties in assembling longitudinal data over an extended period. Debra Bourne wondered if parts of a project could be assigned to students in successive academic years. Iain Peters regretted that information collected by diagnostic laboratories was ‘data heavy but history poor’. Kit Sturgess noted the risks with retrospective surveys: the way in which the data is processed will influence the results. Andy Torrance noted that with good organisation from an academic partner, their lab could provide a lot of prospective data.

Ian Wright noted that ESCCAP is just starting looking at real-time mapping as done in the USA, collecting lab data: what is diagnosed and where (e.g. postcode region). Kit Sturgess perceived a problem with this approach assuming all practices are recording disease at the same frequency, while clinicians who have dealt with a notable case will put more effort into investigations of suspect cases in future, creating apparent disease hotspots. Ian Wright accepted that concern but believed that the data sets being collected are large enough to iron out local differences in recording frequency. Jenny Helm was also concerned regarding bias, but thought screening study data could be useful.

Key points

- If your only diagnostic test for Angiostrongylus vasorum is response to treatment, you will never know the extent of the problem in your area.

- Use the various diagnostic tests available, including Angio Detect, inhouse Baermann's, BAL cytology and PCR as appropriate for each case.

- Consider integrating parasitological screening into routine health checks: these can pick up pre-symptomatic infections, with a negative test giving reassurance that parasite control is being effective.

- No test is 100% sensitive or specific, therefore one negative result does not necessarily exclude A. vasorum infection as a diagnosis.

Treatment of A. vasorum infection — Kit Sturgess

Some canine lungworm cases will present as emergencies needing immediate action to deal with bleeding disorder or cardiorespiratory signs. Others are less urgent. Effective treatments for lungworm are available.

The ESCCAP guidelines advise the use of a macrocyclic lactone-based anthelmintic (varying treatment protocols) or daily administration of a benzimidazole-based anthelmintic for 3 weeks. The guide adds that supportive treatment, with antibiotic and glucocorticoids as well as blood substitute fluids, may be needed in severe clinical cases, and the animal should be rested during the treatment period (at least 2–3 days).

Fenbendazole is the ‘traditional’ treatment for lungworm, although it is not licensed for this use. A suggested dose rate is 25 mg/kg for 20 days in mildly- to moderately-infected dogs, with a 91% efficacy in preventing L1 larvae in faeces. An alternative regimen suggested is 50 mg/kg daily for several days. It has been suggested, with no evidence, that in severely affected dogs, a treatment that removes the worm burden more slowly may be preferable, thus the low-dose fenbendazole regime. (Eric Morgan thought this may have been ‘carried over’ from Dirofilaria treatment, where a rapid kill may be dangerous). This is still often used, despite the presence of licensed alternatives and no evidence of higher efficacy.

For milbemycin oxime, the single published study used an oral dose of 0.5 mg/kg, four times given at 1-week intervals with 14 of 16 dogs showing resolved clinical signs and cessation of shedding of larvae. Milbemycin oxime plus praziquantel tablets are sometimes used once weekly for 4 weeks — the data sheet points to the use of milbemycin alone for three of the four doses, but the monovalent product is not available in the UK.

For moxidectin, the published treatment study (Willesen et al, 2007) using imidacloprid/moxidectin spot-on showed efficacy against mature adults. A single treatment was shown to be 85% effective; the recommended two treatments 1 month apart would be expected to resolve practically 100% of cases.

Clinical experience supports the use of moxidectin as first-line treatment in dogs with mild to moderate disease and in suspected cases. There is no clear evidence regarding treatment to be used in more severe cases and clinicians may have to approach these on a case-by-case basis. Jenny Helm noted that we know little about what happens to the worms after treatment as there are no reports from relevant post mortem examinations. Do worms disintegrate? It is possible that they becomes encapsulated. Kit Sturgess noted that areas of fibrosis/encapsulation would have to be extensive to significantly compromise lung function and lead to clinical signs in pet dogs.

Andy Torrance added that the dead worms would be systematically destroyed by the host macrophages, and that the response to treatment suggested the inflammatory process was successful. Hany Elsheikha pointed out that A. vasorum crosses through the lung parenchyma but lives in the airways. Once dead, they may be coughed up and swallowed (as well as disintegrating and being removed by the immune cells). Ian Wright noted that radiographic improvement can be seen over 3–5 months. Kit Sturgess added that if fibrosis does occur with detrimental effects on lung function, that process may be reversed over a longer term. Hany Elsheikha noted that inflammatory response may worsen initially after parasites are killed.

Jenny Helm said that repeated CT examinations of clinical cases have shown that resolution of lesions lags well behind the resolution of clinical signs following treatment. Kit Sturgess added that with conventional radiography, sensitivity is not sufficient to detect small-scale changes, particularly in the lung field of large-breed dogs.

Kit Sturgess wondered whether a higher dose of moxidectin would be useful, noting that we do not know whether the inflammatory response affects drug penetration. He also noted that clinical cases may have been infected for several months, unlike experimental cases used to produce licensing data., and he wondered how marked weight loss, with loss of fat stores, in severely affected dogs, might affect the pharmacokinetics.

Pre-treatment of A. vasorum cases with glucocorticoids (prednisolone) has been advocated to reduce the immune response to dead and decomposing adult worms following effective treatment. This treatment is recommended by the American Heart Worm Society to reduce the risks of pulmonary thromboembolism due to the elimination of Dirofilaria immitis. This was the perceived wisdom when UK vets started treating lungworm with fenbendazole, but there was no published evidence, only expert opinion (probably based on outcome of the last 2–3 cases treated).

Andy Torrance said in the US it is accepted that pre-treatment is essential when treating dogs with Dirofilaria but that doesn't seem to be the case with A. vasorum. The only feedback received from UK practitioners concerns those A. vasorum cases that died after developing anaphylaxis.

Eric Morgan said it was unwise to extrapolate from work in Dirofilaria as the two parasites are very different; Kit Sturgess noted vets look for parallels with other conditions because of the paucity of relevant information. Jenny Helm noted she uses steroids only if she feels there's an immune-mediated component. Kit Sturgess suggested testing an inflammatory marker such as C-reactive protein might be useful in guiding clinical decisions; there was general agreement.

Management of coagulopathy is important. Bleeding may occur as both a known complication and the main presenting sign. Thromboelastometry findings suggest that hyperfibrinolysis and hypofibrinogenaemia are key abnormalities; changes in other coagulation parameters have been inconsistent. Treatment options include tranexamic acid at 10–20 mg/kg every 6–8 h, total 10–80 mg/kg and fresh frozen plasma at a 20 mL/kg, repeated as necessary. In dogs actively bleeding, tranexamic acid is given IV, otherwise orally.

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a severe, life-threatening complication in A. vasorum cases, occurring in up 15% of cases in a referral-centre (Bristol) study. There are no specific studies on the management of PH in lungworm, so standard therapy is recommended: sildenafil orally 1–3 mg/kg every 8–12 h. It would be wise to begin treatment at the lower dose and monitor the patient response. In the study, 36% of PH cases died within 6 months (vs. just 5% of dogs without PH). Sildenafil does have side effects and should only be used in cases with PH.

There is little reliable data on response to A. vasorum treatment. Success would be measured by the reduction of clinical signs, resolution of thoracic radiographic changes and normalisation of bleeding responses. As no treatment is always 100% effective, repeat treatment may be needed, with results monitored using faecal larval counts. In the one paper on this, antigen detection tests showed good concordance with Baermann. Also BAL could be used; transtracheal washes are underused, but useful where the risks of anaesthesia for BAL are too high. Andy Torrance thought faecal PCR should also be used for monitoring.

Ian Wright noted that preventive treatment should continue afterwards, as there is no evidence of protective immunity to this parasite and the fact that the dog has been exposed once means that there is a lifestyle risk of further exposure. Any other dogs in the household should also receive preventive treatment.

Kit Sturgess noted that all the published data on treatment probably includes only about 200 cases, and many of the articles in the literature are opinion pieces based on this small population. Specialist centres saw many lungworm cases in the 1990s when the condition was apparently new to the UK, but since general practitioners have become accustomed to dealing with these dogs, other than those presenting with unusual clinical signs they are rarely seen in referral practices: they either recover or die. Cases are also being identified much earlier in first opinion practices, before the dog becomes severely ill; treatment is therefore likely to be more effective. Jenny Helm added that more cases are refered in emerging areas for the disease. Also, published studies generally refer to referral populations, which probably feature animals with more severe disease, so published mortality rates are high; she suggested 10–15% might be more likely. Kit Sturgess added that the patients dying during treatment at referral centres are those with severe PH. Those dying with coagulopathies are acute cases, dying early (before treatment). Hany Elsheikha wondered if there is much variation in the response to treatment in lungworm patients. Kit Sturgess andJenny Helm thought that the variety in the presenting signs/clinical condition is the main influence on treatment choice and treatment response. Dogs with mild coughing will probably receive treatment for lungworm at the primary care centre and not need referral. Identifying differences in response to treatment would require a grading system for the severity of these presenting signs — difficult because of the range of different clinical presentations. There is also no consistent relationship between the severity of the damage seen on CT images and clinical outcome.

Eric Morgan felt that (excepting peracute cases) the greatest mortality risk factor in lungworm cases is ignorance of the primary care vet. Vets need to be aware of the risks of exposure to the parasite and both the use and limitations of the current diagnostic methods, to reduce delayed diagnosis. With the changing epidemiological picture, practitioners should not assume that the parasite is absent from their local area. Kit Sturgess thought Angio Detect should be ideally be available in practices to assist early diagnosis in coagulopathy cases.Ian Wright considered that raising general awareness in areas that think they are lungworm-free would have the biggest impact.

Andy Torrance noted that practitioners can seek advice from the commercial laboratories, as they will have dealt with hundreds of similar cases; labs can raise awareness. Kit Sturgess noted that two doses of an effective anthelmintic might become standard practice early on in treatment of a coughing dog. Lungworm would rarely be confirmed, as first opinion practitioners are appropriately focused on making the patient better. Pressure to carry out further tests could return if anthelmintic resistance becomes an issue.

Key points

- Early identification allows earlier treatment that is therefore more likely to be effective.

- Moxidectin is appropriate for treatment of dogs with mild to moderate disease, and in suspected cases.

- Treatment of severe cases needs to be approached on an individual patient basis.

- More than one dose of an appropriate anthelmintic is needed for an effective cure of clinically affected animals.

- The use of tranexamic acid needs to be more widely known.

Practical aspects of control in dogs — Ian Wright

There are good sources of advice on dealing with A. vasorum but practitioners need to generate their own information on local risk and share it with colleagues. All small animal practices must explain the necessity of regular preventive healthcare to their clients.

A free query service is provided by ESCCAP UK & Ireland. Questions about angiostrongylosis remain a common source of calls (third behind heartworm and leishmaniosis). Surprisingly in view of the severity of the condition, many of the questions focus on preventive care: is prevention needed? Does that have to mean an anthelmintic? If so does it have to be given monthly? There is a great deal of push-back at the moment from the public about veterinary medicine use, with concern about the environmental effects of residues. In answering queries, ESCCAP advises that owners should consider lifestyle risks (e.g. dogs that repeatedly eat molluscs, grass eaters, coprophagia, use of outdoor drinking bowls, drinking from puddles, and leaving food out for wildlife) together with geographic risks, based on national case recording, fox prevalence maps and diagnoses in dogs locally; these can all be found free online.

The key to better determining risk to dogs is more regular testing for A. vasorum by veterinary practices and sharing of the results. Vets are aware that lungworm distribution is patchy; they have difficulty in deciding whether lungworm is an immediate problem for their clients' animals. The Baermann method is cheap but is time-consuming; needs pooled samples; clinicians may find it difficult to persuade clients to collect the fresh faecal samples; and both sensitivity and specificity can be poor. The Angio Detect blood test offers rapid results (15 minutes) with higher sensitivity and specificity, and allows quick diagnosis in suspect cases and for pre-operative screening.

Practitioners can share the occurence of cases through social media and by contacting the local press. Publicity campaigns run by animal health companies on television and in the national press have been highly successful in raising awareness. It has become clear that there is no part of the country where there is zero risk of lungworm.

Anthelmintic treatment is the only guaranteed preventative. Once in an area, lungworm cannot be eradicated, due to the large IH population and the wildlife reservoir. No strategy will 100% prevent exposure to the IHs. Nematophagous fungi can destroy L1 larvae, but there are practical limitations to treating any large area. Encouraging owners to pick up their dogs' faeces will help but will have no effect on the wildlife reservoir. There are also secondary preventive measures such as bringing dog toys and water bowls indoors at night and walking dogs at those times of day when they are less likely to encounter slugs. Owners should be informed of the risks to enable them to make an informed decision. Monthly treatment with moxidectin or milbemycin oxime is highly recommended in known endemic areas, to prevent angiostrongylosis. Advocate (moxidectin + imidacloprid) has a licence claim against L4, immature adults (L5) and adults, with 100% parasite elimination. Other products claim prevention of disease through reduction of L5 and adult worms.

The key issue in disease prevention is to ensure good owner compliance and providing better overall parasite protection. Problems most likely arise due to owner difficulty applying treatment, and particularly due to owner forgetfulness, rather than product inefficacy. It is important for vets not to simply assume that all parasiticide treatments dispensed are used. ESCCAP has lauched a diagnostic recommentation sheet for owners. Pet wellness plans assist compliance, and at least annual screening of pets for lungworm should be a part of any wellness plan for dogs in areas where the parasite is known to be present, to screen for efficacy (compliance). He admitted to occasionally treating a few days late himself, and Jenny Helm also admitted occasionally forgetting her dog's preventative and suggested that methods such as monthly postal distribution of parasiticides can help.

Key points

- Monthly effective anthelmintic is key.

- A video or quote from general practitioners discussing how they felt following unexpected bleeding during routine surgery can be potent.

- Compliance is the biggest issue.

Other UK canine lungworms and their clinical significance — Hany Elsheikha

The canine respiratory tract is the preferred environment for a range of nematodes with practically worldwide distribution. Little is known about these. Practitioners need to know what treatment options are available and how to prevent reinfection.

Other parasites besides A. vasorum have the potential to cause cardiorespiratory disease in dogs. Between them they infect all parts of the respiratory tract: sinuses (Eucoleus boehmi), trachea (Filaroides osleri, Eucoleus aerophilus and Crenosoma vulpis) and bronchi/bronchioles (F. osleri, F. hirthi, E. aerophilus, C. vulpis). None are commonly diagnosed and we know little about their prevalence. These are mainly in the Metastrongyloidea and are morphologically similar to one another; it can be challenging to identify which species is involved when they appear in a faecal sample (eggs from some intestinal species are also similar). Serological (antigen or antibody) and molecular techniques may assist.

Filaroides (Oslerus) osleri has a direct life cycle (no gastropods involved); infection occurs by ingesting L1-infected faeces or by direct transfer of L1 in sputum. The adults live within nodules in the mucosa of the distal trachea and tracheal bifurcation. Prevalence in the UK is unknown. Clinical signs may include a chronic cough, sometimes wheezing; this may develop to exercise intolerance, dyspnoea, even death. The strong immune response to adults in the trachea and bronchi causes the worm to encapsulate. On bronchoscopy, the parasite may be seen as nodules on the mucosa, particularly at the tracheal bifurcation. L1 larvae will be present in the faeces and in BAL fluid, along with abundant eosinophils. Resolution of tracheal and bronchiolar nodules may take several weeks post-treatment.

Eucoleus aerophilus (Capillaria aerophila) inhabits the trachea, bronchi and bronchioles of dogs, cats, foxes, wolves, raccoon dogs, lynxes mustelids, hedgehogs etc. Apart from a slight cough, infection is usually asymptomatic in dogs and cats. Pets may be infected by swallowing an infective egg or a paratenic host (e.g. an earthworm). The parasite migrates from the gut to the lungs. It may be detected using faecal flotation or a tracheal wash.

Eucoleus (Capillaria) boehmi infects the mucosa of the nasal cavity and passages, plus the frontal and paranasal sinuses, of dogs and foxes. Rhinoscopically it can be seen on the epithelial lining of the nasal turbinates: 1.5–4 cm long, with a serpentine shape. Infected hosts may exhibit sneezing, rhinitis, serous to mucopurulent nasal discharge and sometimes severe epistaxis, which may require a blood transfusion. Its overall biology is similar to that of E. aerophilus. It is treated with fenbendazole, 50 mg/kg orally every 24 hours for 2 weeks. Dogs may have been treated with antibiotics, antihistamines and steroids before diagnosis.

Eggs of E. boehmi, E. aerophilus and the whipworm T. vulpis are similar, all with polar plugs, but can be distinguished on microscopic examination. When looking at faecal smears, adjusting the focus slightly may help to identify the delicate pits on the surface of E. boehmi which contrast with the coarser pitted appearance of E. aerophilus, while T. vulpis is slightly larger with a smooth shell surface and polar plugs that, unlike the others, are aligned symmetrically on opposite sides of the egg. For E. boehmi, additionally larval development may have started, with the larva visibly retracted from the shell.

Filaroides hirthi and F. milksi are both found in the terminal airways, bronchioles and alveoli of dogs. Infection is usually asymptomatic, but coughing and dyspnoea may occur and miliary nodules may be detected on necropsy. The life cycle is direct, via ingestion of L1 larvae. Transmission will often occur in kennels, because the larvae are infectious when passed out in the faeces. Diagnosis is made through the detection of L1 or embryonated eggs in faeces or airway cytology specimens, while radiographic examination may show a diffuse interstitial or focal nodular pattern.

Crenosoma vulpis, known as the fox lungworm, is found in wolves, coyotes, raccoon dogs and badgers in Europe and North America, and has been identified in domestic dogs in the UK. It is found in the trachea, bronchi and bronchioles. It has an indirect life cycle via mollusc intermediate hosts, often the common garden snail Helix aspersa. It produces clinical signs of coughing, sneezing, exercise intolerance and inappetence. Diagnosis is through the detection of L1 larvae in faecal samples (Baermann or faecal flotation). A single oral dose of 0.5 mg/kg milbemycin oxime will resolve clinical signs and stop larval shedding in faeces. Other successful treatments reported include febantel, fenbendazole, ivermectin and moxidectin. The parasite has a prepatent period of just 18–21 days. Ian Wright noted that despite this, some products have identical monthly disease prevention licences for this and A. vasorum.

There is no single product that can be advised against all of these parasites. Moxidectin (e.g. Advocate) and milbemycin products have licence indications for treatment of C. vulpis, with similar efficacy as against A. vasorum. Ian Wright said he also understood that Advocate showed consistent efficacy against E. boehmi. Fenbendazole still has a treatment licence for F. osleri, but not for any of the other species.

Hany Elsheika explained that signs may recur despite treatment, due to dogs eating their own faeces and causing reinfection. Owners are advised to prevent coprophagia and to arrange further faecal examinations to ensure that the dog is still negative. Since egg shedding is cyclical, multiple faecal examinations may be needed to detect infection and ascertain the real prevalence — is the parasite rare or is it just rarely diagnosed? Clinical signs vary (including asymptomatic). These other respiratory tract parasites should be considered among the differentials in any dog showing respiratory disease or chronic nasal discharge, especially in fox-endemic areas, and a faecal examination performed. Debra Bourne noted that overreliance on PCR could lead to some species being missed (because they are not tested for).

Kit Sturgess suggested that routine treatment for A. vasorum has contributed to the control of these more unusual parasites, which is one reason why they are rarely diagnosed in practice. Eric Morgan mentioned studies in Germany that have demonstrated an increase in the prevalence of A. vasorum but no change in C. vulpis as prevalence of this species was already high. Andy Torrance added that there have only been two cases of C. aerophila infection in BAL at his laboratory since 2001; after A. vasorum, the great majority of respiratory parasite cases were C. vulpis (about half as many cases). Eric Morgan thinks improved testing may be needed. Ian Wright noted that Eucoleus aerophilus is very common in foxes; perhaps the direct life cycle reduces dog exposure? Under-diagnosis is also a possibility.

Additionally, some gastrointestinal nematode species may cause respiratory signs. In particular, the canine hookworm Ancylostoma caninum and the threadworm Strongyloides stercoralis. The latter is a more serious disease in puppies than adult dogs and can be a problem in kennels. It is zoonotic and may cause disseminated infection in immunocompromised patients. It can be treated using oral fenbendazole at 50 mg/kg for 5 days, which will halt the production of larvae and improve clinical signs. Ivermectin has also been used but it may have a narrower safety margin in certain breeds, such as collies.

Key points

- Consider lungworms such as Oslerus osleri, Capillaria aerophila, Eucoleus (Capillaria) boehmi, Filaroides hirthi, F. milksi and Crenosoma vulpis, not only Angiostrongylus vasorum, in differential diagnoses.

- Use a range of diagnostic tools to identify larvae in bronchoalveolar lavage or faecal samples.

Feline lungworms in the UK: gone or just forgotten? — Hany Elsheikha

Feline lungworm Aelurostrongylus abstrusus is present in the UK cat population and can potentially cause significant health problems.

Feline lungworm is a neglected disease, but it is certainly present. Like its equivalent in dogs, infection of cats with Aelurostrongylus abstrusus is a potentially serious health problem in feline medicine. It is a cause of pneumonia, sometimes fatal, affecting all ages but particularly kittens and immunocompromised and old cats. The parasite has a worldwide distribution. A study of cats in England found a prevalence of 1.7% (17/950 faecal samples, many from rescue shelter cats). Many aspects of its epidemiology are still unknown.

Adult A. abstrusus are about 1 cm long and live in the terminal bronchioles and alveolar ducts. Eggs hatch to L1 larvae and migrate to the upper respiratory tract where they are swallowed and pass out in the faeces. The L1 are ingested by land gastropods and mature to the L3. Cats are infected by ingestion of gastropods or paratenic hosts (rodents, amphibians, birds) carrying the L3.

Larvae in the alveolar spaces result in both inflammation and mucus production, which can prevent gaseous exchange. This should be considered as a potential cause of disease in any cats presenting with evidence of pulmonary disease, even those with mild signs. However, cats also may become infected and shed large numbers of larvae in their faeces without showing clear clinical signs. Infection risk will vary according to geographical area and the cat's lifestyle.

A number of other metastrongyloid lungworms are found in cats, including Troglostrongylus sp., Oslerus rostratus and E. aerophilus. These all have a similar biology and co-infections occur. They may be distinguished morphologically using standard light microscopy, based on body length; round or pointed head; the tail shape; and presence or absence of cuticular spines.

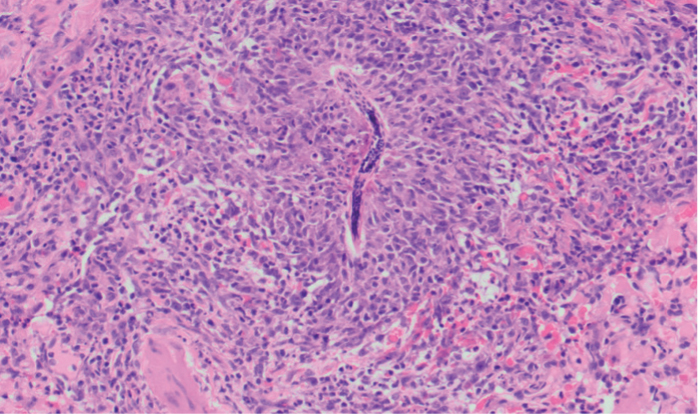

Cats with heavy infection develop chronic cough, wheezing, sneezing and mucopurulent discharge, with progressive dyspnoea, anorexia and emaciation. Gross lung lesions are grey nodules scattered across the lung surface, sometimes in clusters. Histopathology shows severe pulmonary inflammation.

A broad range of anthelmintics is effective against A. abstrusus: moxidectin + imidacloprid; milbemycin oxime + praziquantel, fenbendazole; praziquantel + emodepside; fipronil + S-methoprene + eprinomectin + praziquantel. Advocate, Broadline, Panacur and Profender are licensed; clinicians should check the data sheets if A. abstrusus is diagnosed or is strongly suspected. A second treatment a month later is strongly recommended. Patients need supportive care: corticosteroids such as dexamethasone to reduce bronchial inflammation; antibiotics if secondary bacterial infection; fluids for those in poor physical condition; bronchodilators, mucolytics, oxygen, and thoracentesis as needed. Kit Sturgess noted that no coagulopathy has been described. Andy Torrance noted the adults live in the airways, not blood vessels. Ian Wright noted it is rarely definitively diagnosed; Kit Sturgess added that feline practitioners are aware and will give appropriate anthelmintics as part of treatment of respiratory cases; Ian Wright agreed. Iain Peters noted they do have a PCR; Andy Torrance added that they use this in cats with eosinophilic airway disease but have not detected A. abstrusus. Ian Wright suggested prevalence may be higher in feral/outdoor cats, which are less likely to be treated or have diagnostic tests done.Robyn Farqhar noted that cats receiving flea/worm treatment are less likely to be infected; Kit Sturgess added that coughing cats most likely to be tested (those sent to referral practices) are even more likely to have had anthelmintic treatment, while those with low-grade cough will not be tested. Ian Wright noted that most anthelmintics are effective; Jenny Helm added that again compliance is an issue. Kit Sturgess wondered if some adverse reactions to parasiticides might actually be due to lungworms being killed.

A study from 12 European countries found that lungworms were the second most frequently detected nematode group in cats, with A. abstrusus the most common lungworm species. The UK prevalence of 1.7% was towards the lower end of the prevalence range in Europe (varying from 0.38% in Croatia to 43.1% in neighbouring Albania). The 1.7% may easily be an underestimate as Baermann's is normally used, which requires viable larvae, thus various factors may affect retrieval of larvae: time before the sample is collected; cat litter type (larvae quickly become dehydrated and lose viability on some materials) and transport time. Additional factors are the inability to detect larvae in the prepatent period; cats with low parasite burdens; and cessation of shedding, which occurs in some cats and will give false negative results. Also, ideally, Baermann's technique should be conducted on fresh samples collected on 3 consecutive days, which is not always feasible.

Serological methods (ELISAs) may be useful in future surveys, in conjunction with faecal analysis. Eric Morgan noted that lifestyle factors will influence exposure: probably highest in outdoor cats, which are also those least likely to receive anthelmintics.

Prevalence also varies across a country. The Nottingham study showed occurence throughout England but with varying prevalence, which may be related to the availability of IHs and parantenic reservoir hosts (wildlife species) able to maintain the parasite lifecycle. Intermediate host factors may explain the lack of positive results in samples collected in Cambridge (the relatively dry climate may be less conducive to slug survival).

Age did not affect prevalence in this study, although age has shown an effect in other studies (lower in kittens under 11 weeks in one study, higher in cats under 2 years in another). As in previous studies, breed, sex and neutering did not affect prevalence. Maintaining cats indoors did appear to provide significant protection, but there was no evident difference between infection rates in pets with outdoor access, strays and feral cats (possibly due to the smaller numbers in the latter two categories). There was no correlation between deworming history and risk of infection. However, the data may be insufficiant to detect the effect of anthelmintics, and the frequency and timing of deworming are likely to affect infection risk.

A case in a kitten that had been treated once and relapsed with severe infection 6 weeks later emphasises the need for two treatments (possibly larvae in refugia develop after treatment?). Littermates were also affected, suggesting a common source. Ian Wright said that monthly anthelmintic treatment was recommended for cats that hunt, and a product effective against feline lungworm should be recommended. Eric Morgan added that regular anthelmintic treatment also reduces risk from zoonotic parasites such as Toxocara spp.

Key points

- Accurate estimates of the prevalence and real burden of Aelurostrongylus abstrusus in cats are lacking.

- Prevalence found using Baermann's is likely to be an underestimate.

- More surveys are needed, differentiating between A. abstrusus and other feline lungworms.

- Severe lesions and fatal infection can occur without treatment.

- Treating twice is highly recommended.