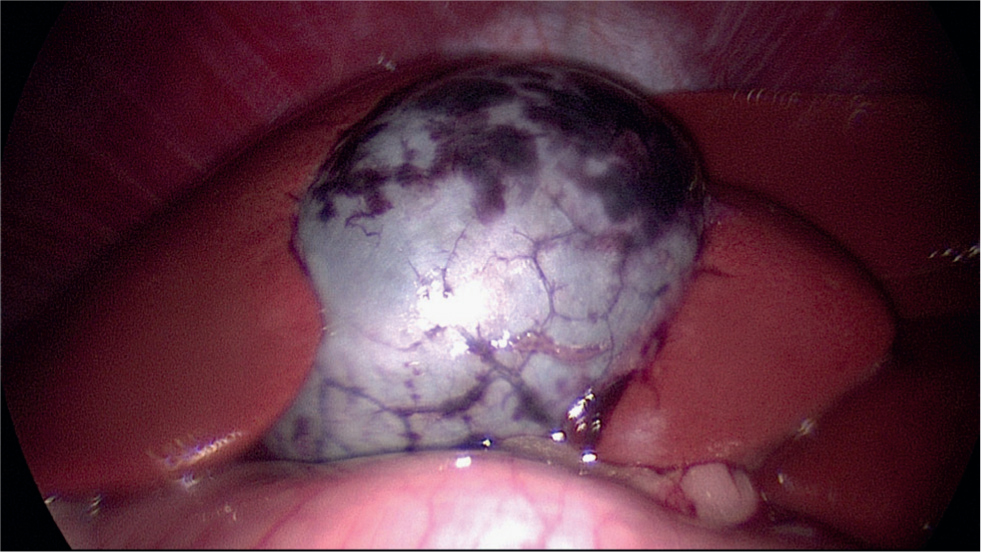

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a routine and common procedure in human medical practice and is the treatment of choice for gallstone disease and acute cholecystitis, as it has been shown to be less invasive and safer than traditional open surgical methods (Barkun et al, 1992; Hendolin et al, 2000). It is a much less common procedure in veterinary medicine, where gall bladder disease is less common. When cholecystectomy is indicated in veterinary medicine, open procedures by laparotomy are usually performed. Indications for cholecystectomy in dogs and cats include necrotising cholecystitis, gall bladder trauma or neoplasia, symptomatic cholelithiasis and gall bladder mucocoele. Of these, uncomplicated gall bladder mucocoeles are most common and are probably the most suitable for treatment with laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Lhermette et al, 2020). Gall bladder mucocoeles are more common in older dogs and certain breeds have a predisposition, in particular the Border Terrier, the miniature Schnauzer, Shetland Sheepdog and Cocker Spaniels. There does not appear to be any sex predilection, but there is a strong association with Cushing's disease which increases the risk of mucocoele development 29-fold in susceptible breeds (Mesich et al, 2009). Exogenous administration of corticosteroids can also increase the risk, as can dyslipidaemia, although the underlying cause is not yet fully understood. Biliary sludge is a common and incidental finding in dogs and can make diagnosis of early cases of mucocoele difficult on ultrasound examination (Figure 1).

Mucocoele formation starts with a cystic mucosal hyperplasia and secretion of a thick gelatinous mucus which may eventually fill the whole gall bladder and eventually the hepatic and common bile ducts. Most cases show elevated alanine transaminase, alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin levels, but these can be normal in the early stages of disease. Leucocytosis may also be present if there is significant inflammation. On ultrasound, initial signs are usually of an area of non-gravity dependant sludge which, over weeks or months, may develop into the classic striated or stellar ‘kiwi fruit’ appearance. Mucocoeles may be unsymptomatic or they may result in vague clinical signs such as lethargy, inappetance, abdominal pain. Alternatively, they may cause more acute signs such as severe abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhoea and jaundice. In some cases, extrahepatic biliary obstruction may occur or the mucocele may rupture, leading to bile peritonitis (Scott et al, 2016), so cholecystectomy is the treatment for choice for all biliary mucocoeles.

Before considering laparoscopic cholecystectomy, it is essential to ensure that the correct instrumentation is available (Box 1). It is also essential that the surgeon is experienced in laparoscopic techniques.

Box 1.Basic equipment required for laparoscopic cholecystectomyLaparoscopic equipment required for cholecystectomy:

- 5mm endoscope (0° or 30°)

- Endoscopic light source

- Camera and monitor

- Laparoscopic insufflator

- Light guide cable.

- 6mm endoscopic cannulae x3 (with trocars or ternamian tipped)

- 11mm cannula (with 10mm to 5mm reducer)

- electrosurgical generator (monopolar/bipolar)

- Surgical suction machine

Hand instrumentation for the procedure includes:

- 5mm palpation probe

- 5mm fan retractor

- 5mm right-angled dissecting forceps

- 5mm laparoscopic scissors

- 5mm monopolar hook electrode (or harmonic ace handpiece - optional)

- A vessel sealing device, such as Ligasure (optional)

- 5mm suction/irrigation wand with trombone button attachment

- 5mm and 10mm laparoscopic clip appliers

- 5mm or 10mm endoscopic retrieval bag of a suitable size to contain the gall bladder

- Routine surgical laparotomy kit

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is usually performed via a four-port approach, requiring a surgical assistant. Alternatively, a single port approach using a single port access system, such as a SILSTM device (Covidien), positioned at or near the umbilicus can be used. This device incorporates three ports and is usually used with articulated instrumentation. Retraction of the gall bladder is more difficult using a single port approach and a second port in the upper left quadrant of the abdomen is often incorporated to allow placement of a fan retractor.

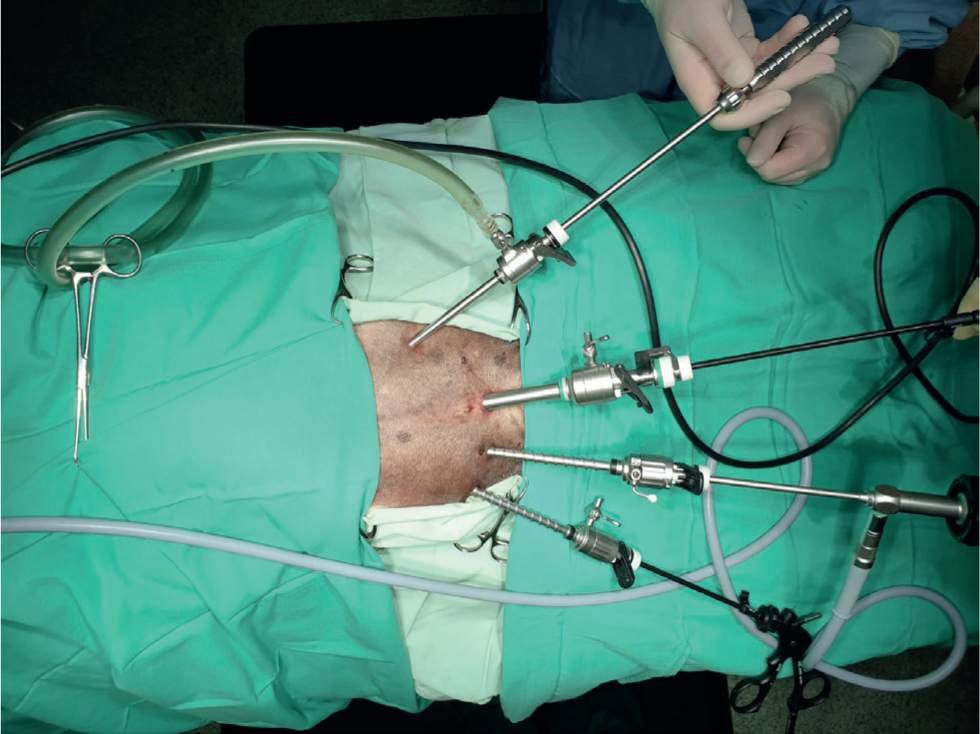

The anaesthetised patient is placed in dorsal recumbency. A 20° negative trendelenburg (head up) position allows access to the liver and relieves pressure on the diaphragm. Lidocaine or bupivacaine is injected subcutaneously at all port sites to improve post-operative analgesia. Port (cannula) placement will vary slightly according to patient size, so the following should be taken as a general indication only as precise measurements will vary. The Veress needle is placed just caudal to the umbilicus in the midline, at the site of the primary port. A small 1mm skin incision is made with a number 11 blade and the abdominal wall is grasped between the index finger and of the non-dominant hand to elevate the abdominal wall and allow introduction of the Veress needle at a 45° angle with a short stabbing motion, into the pocket so created. Once placed, the abdomen is insufflated with CO2 to around 8–10mmHg using an automatic laparoscopic insufflator. Following insufflation, the Veress needle is removed and the incision is enlarged to 9mm to allow placement of an 11mm trocar and cannula. A 6mm reducer is used on this cannula to allow placement of 5mm instrumentation, without losing the seal. A 5mm 30° endoscope attached to a light guide cable and camera system is then introduced into the abdomen and a quick examination is carried out to ensure no iatrogenic damage has been done. A 5mm 0° endoscope may also be used, but the 30° endoscope enables the endoscope to be held away from the instrumentation, preventing ‘sword fighting’, and allows a more all-round view of the surgical site. A 4mm incision is then made approximately 5–8cm lateral and 3–5cm cranial to the umbilicus in the left cranial quadrant, for placement of a 5mm cannula under direct visualisation through the endoscope. Two further ports are placed in a similar manner, 3–5cm and 5–8cm lateral to the umbilicus on the right side. These should be placed on an arc formed by an imaginary circle around the gall bladder at its centre to allow triangulation of the instruments down to the surgical site (Figure 2).

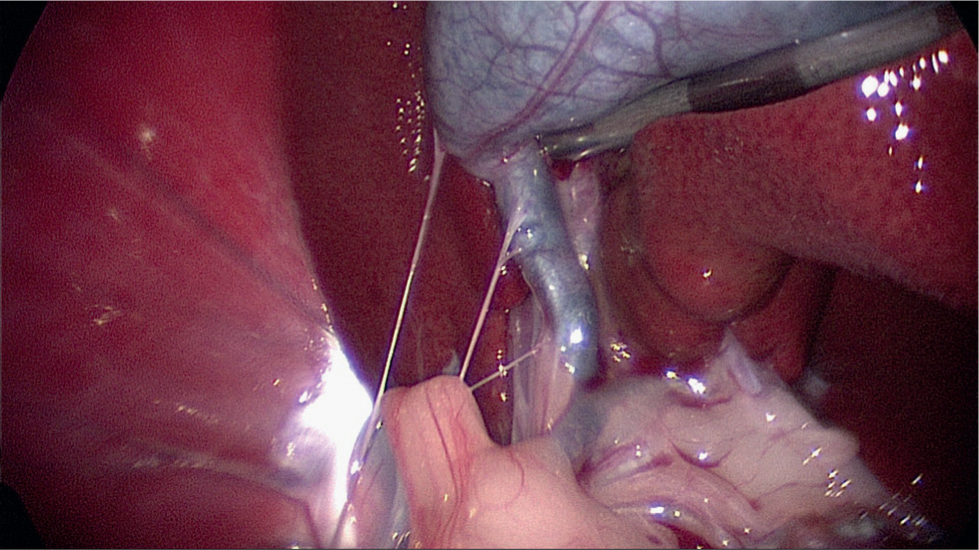

A palpation probe may be inserted through the cranial port in the left anterior quadrant to allow examination of the gall bladder and biliary tree (Figure 3). In obese animals, this will need to be passed around or underneath the falciform fat. The gall bladder and adjacent lever lobes will need to be elevated to enable dissection of the bile duct and examination of the biliary tree. This can be accomplished with the palpation probe or a fan retractor, but care must be taken to prevent the gall bladder from dislodging during dissection. If the gall bladder is not too friable, Babcock's forceps provide a more secure hold and can be used to hold and elevate the gall bladder as required. The endoscope may be maintained in the umbilical port or can be moved to the port just to the right of the midline, between the two other instrument ports, to allow for a more ergonomic approach.

Excellent visualisation is usually afforded by the magnification and illumination provided by the endoscope. However, in some cases, where severe cholecystitis or gall bladder rupture has resulted in multiple adhesions, visualisation of the biliary tree is obscured. In these cases, careful dissection or conversion to an open laparotomy is required.

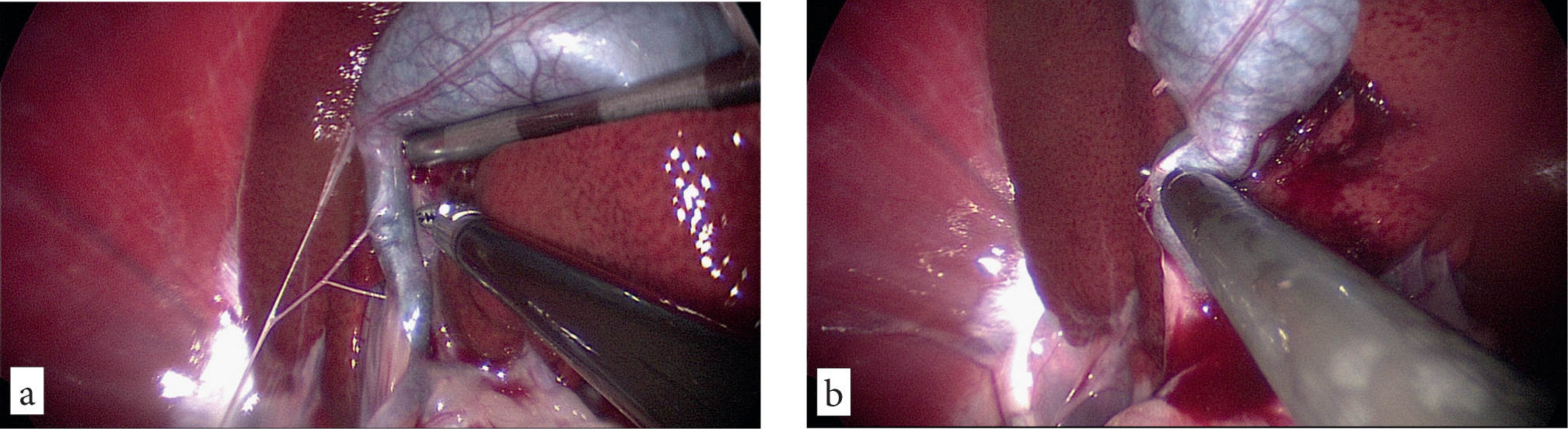

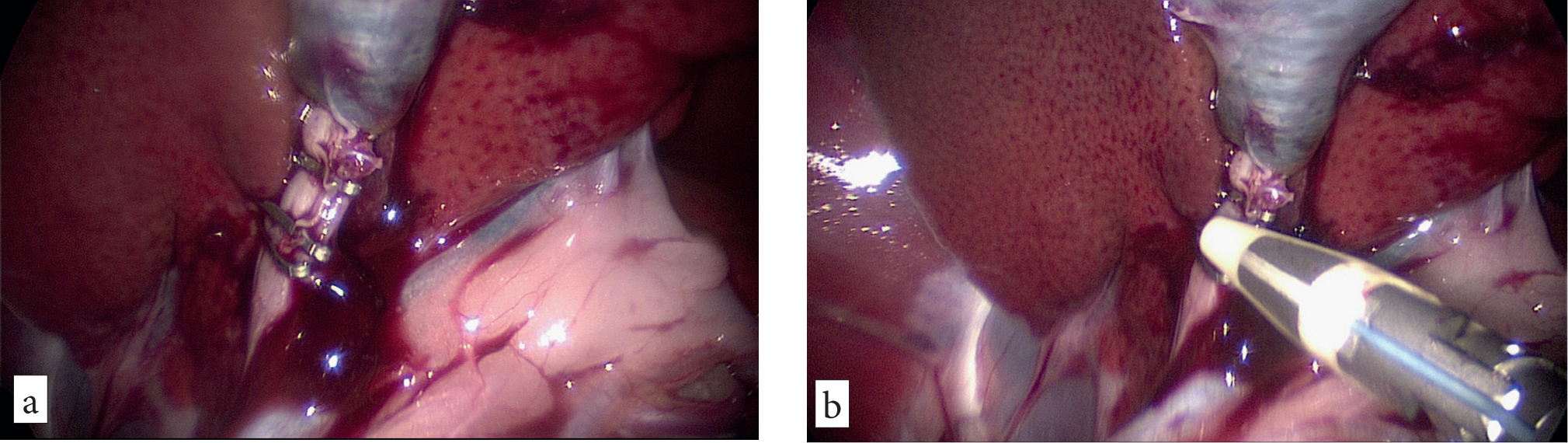

Right angled laparoscopic forceps or curved articulated dissecting forceps (Kelly's forceps) are introduced through the umbilical port to enable careful blunt dissection around the cystic duct (Figure 4a). The cystic artery lies in the area behind the cystic duct (an area known as Calot's triangle in humans). This is usually ligated separately in humans, but is relatively small in the dog and is normally incorporated into ligation of the cystic duct. However, there may be some haemorrhage when dissecting around the cystic duct and this can be removed by suction and irrigation with normal saline through the instrument port on the far right of the abdomen. Care must be taken to dissect the cystic duct above the point of entry of the first hepatic duct. Once the dissection is complete, the tips of the dissecting forceps will be visible around the other side of the cystic duct over the whole length between the gall bladder and the entry point of the first hepatic duct (Figure 4b).

Ligation of the cystic duct can be accomplished in a variety of ways, depending on the patient size and the size of the cystic duct, which can be quite distended in some patients. Vessel sealing devices such as the Ligasure have been trialled, with some success in both humans (Schulze et al, 2010) and animals (Marvel and Monet, 2014). However, the author's preference is to use endoscopic clips or sutures to ensure adequate closure of the duct without the risk of collateral thermal damage in a small space. Either 5mm or 10mm laparoscopic clips may be used, depending on the size of the patient and the size of the duct. Often the duct is quite dilated, and the clips must be sufficiently large to reach right over the duct and provide a good seal. If there is any doubt, it may be preferable to use intracorporeal or extracorporeally tied sutures.

Four clips or sutures are placed on the cystic duct between the gall bladder and the first branch of the hepatic duct, leaving a space between the proximal and distal two clips to allow sectioning of the duct with scissors or a vessel sealing device (Figure 5aandb).

Care must be taken when placing the distal clip or suture to not compromise the hepatic duct. Once the clips have been placed and the cystic duct has been transected, the site is checked for leaks and the end of the cystic duct attached to the gall bladder is grasped with Babcock's forceps and elevated to allow dissection of the gall bladder from its fossa on the liver. This is best accomplished using monopolar electrosurgery or a Harmonic Ace handpiece (Ethicon). A monopolar hook electrode is ideal for this function, as it allows accurate and careful dissection.

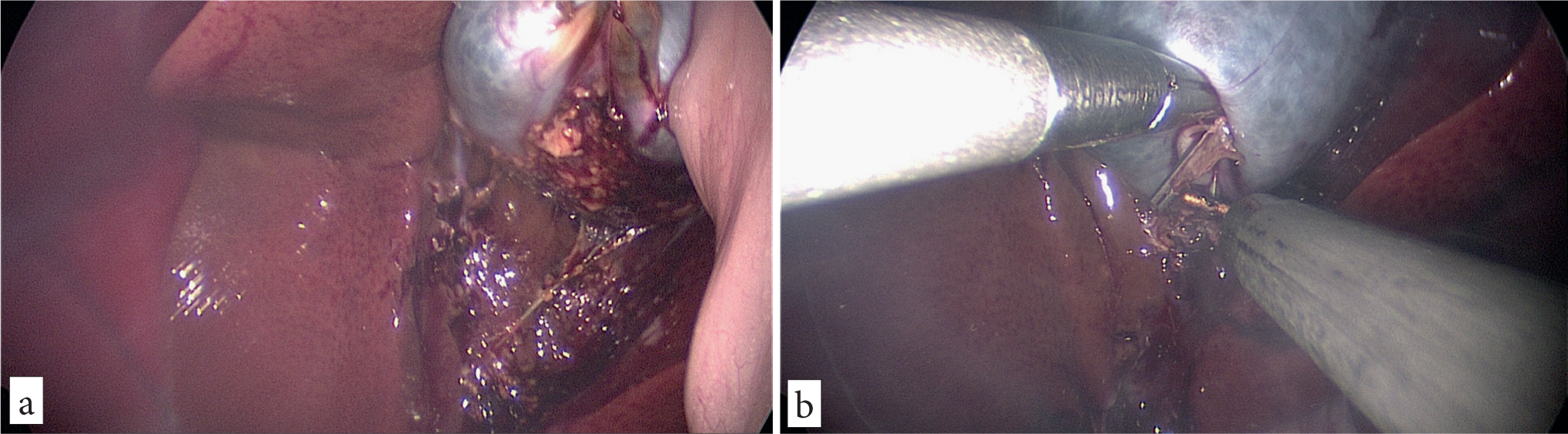

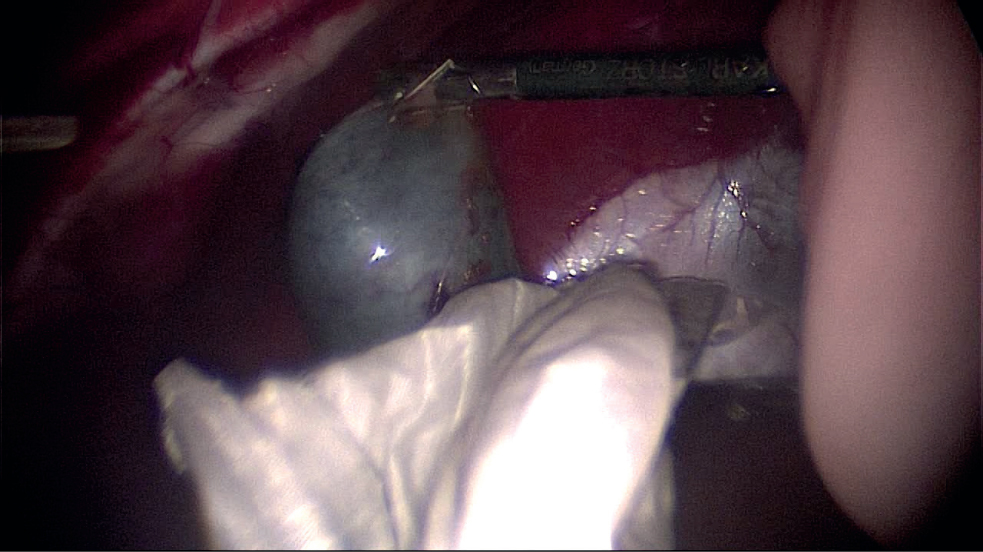

Great care must be taken not to cause a rupture while dissecting close to the gall bladder and to provide continuous upwards traction (Figure 6a). There will inevitably be some haemorrhage, which can be controlled with the monopolar hook (Figure 6b). Saline irrigation and suction can be used as required. The gall bladder is dissected completely free and then placed in a laparoscopic retrieval bag introduced through the umbilical port (Figure 7). Once deployed in the abdomen the bag has a wire loop that maintains the opening for placement of the specimen, and a draw string to close the opening for withdrawal through the abdominal wall.

Once enclosed in the bag, the 11mm umbilical port is removed and the edges of the retrieval bag are exteriorised through the abdominal wall, the gall bladder is brought up to the incision site. A 20ml syringe with an 18-gauge needle attached are then used to drain the gall bladder as much as possible to reduce its size. If the bile is too thick and mucoid, an incision is made in the gall bladder with a number 11 scalpel blade and the contents aspirated using suction to reduce its size as much as possible. The bag is then grasped and if necessary, the abdominal incision enlarged a little to allow the gall bladder to be withdrawn from the abdomen. The 11mm port is then replaced and 3–5 liver biopsies are taken using 5mm endoscopic clamshell biopsy forceps. These are then submitted for culture and histology.

Following a final inspection of the surgical site to ensure all haemorrhage has stopped, any remaining blood or bile leakage should be removed with irrigation and suction. The abdomen desufflated and the abdominal port sites are closed routinely. The gall bladder is submitted for histology and a sample of bile is sent for cytology and culture and sensitivity.

Intra-operative cholangiography is often carried out in humans to rule out the presence of gallstones or blockages in the common bile duct. This is rarely done in dogs for uncomplicated mucocoeles, although it should be considered in cases of symptomatic cholelithiasis.

Post-operative care consists of exercise restriction and pain relief for 5–7 days as appropriate. Antibiosis is provided in the face of pre-existing infection or following culture and sensitivity results.

When carried out early, before severe cholecystitis, adhesions or gall bladder rupture have occurred, this is typically a successful procedure with a relatively rapid recovery and a good prognosis.

KEY POINTS

- Cholecystectomy is routinely performed laparoscopically in humans in preference to open laparotomy.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a practical alternative to open cholecystectomy in the dog.

- A minimally invasive approach results in reduced rates of morbidity and quicker recovery.

- Careful case selection is key and early intervention is advised.

- Correct instrumentation and experience in laparoscopic technique is essential.