Uroabdomen, defined as collection of urine within the peritoneal cavity or the retroperitoneal space, is an uncommon but life-threatening condition seen in small animal practice. It is caused by loss of integrity in any part of the urinary tract from the kidneys proximally to the pelvic urethra distally.

Abdominal trauma is the most common cause of uroabdomen in dogs, and the urinary bladder is the site of leakage in more than 50% of cases (Grimes et al, 2018). Traumatic injury to the pelvic and prostatic urethra has been reported in conjunction with pelvic fractures (Aumann et al, 1998; Hoffberg et al, 2016). Male dogs are more commonly affected than females, as the long and narrow urethra in males cannot quickly adapt to a sudden increase in intra-vescicular pressure (Thornhill and Cechner, 1981). Iatrogenic uroabdomen can occur after any surgery involving the abdominal portions of the urinary tract, or secondary to traumatic urethral catheterisation. Cystocentesis of a healthy bladder rarely results in uroabdomen, although underlying pathological conditions of the bladder may increase the risk.

Clinical signs

Prompt recognition and early treatment of uroabdomen are essential to maximise the likelihood of a successful outcome. Clinical signs are often not specific and might not appear in the first 24 hours after the traumatic event.

Lethargy, anorexia and vomiting in any patient with a known history of trauma, urinary tract disease or procedures involving the urinary tract should prompt clinicians to consider uroabdomen in the differential diagnoses. Palpation of the urinary bladder or an animal's ability to urinate do not rule out the possibility of a bladder rupture or uroabdomen. In animals with a history of significant trauma, particularly trauma affecting the pelvic limbs, pelvis or abdomen, the integrity of the urinary tract should be established once the animal has been stabilised.

When early diagnosis is missed, animals may present in circulatory shock, recognisable by signs such as tachycardia, weak peripheral pulses, pale mucous membranes and prolonged capillary refill time. Abdominal distension and ballotable ascites can be seen when a large volume of fluid is present.

Diagnosis

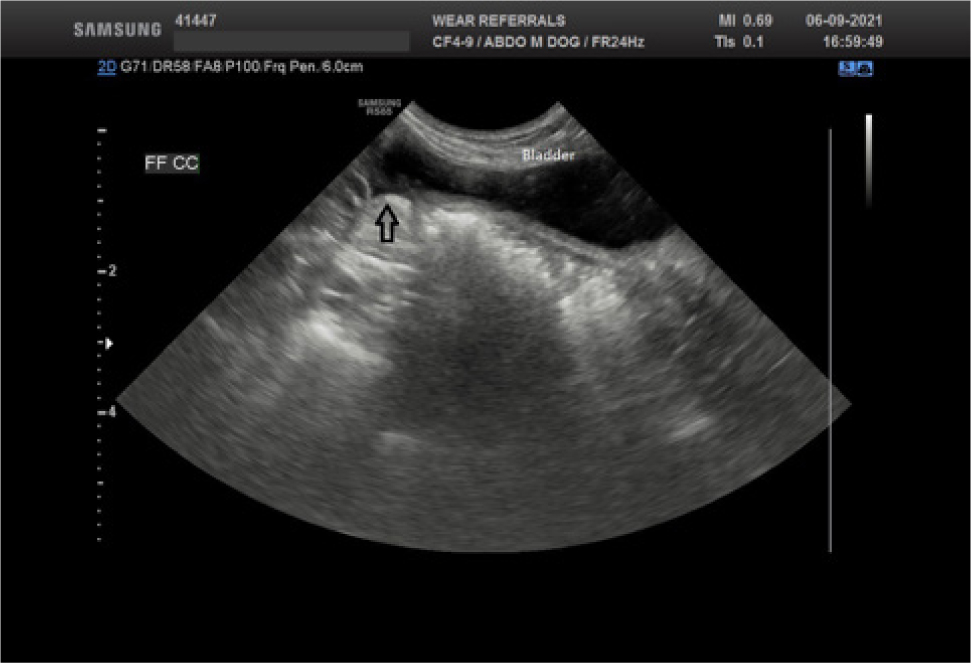

Uroabdomen is diagnosed by identifying and evaluating peritoneal or retroperitoneal free fluid, after collection via abdominocentesis. A point-of-care ultrasound examination of the abdomen is quick, inexpensive and can easily identify large volumes of free fluid, even when performed by inexperienced operators (Lisciandro et al, 2009). A small amount of fluid can be more challenging to visualise; clinicians can carefully evaluate the ultrasound for anechoic pockets in the gravity-dependent sites, concentrating on the region between the liver lobes and the bladder area (Figure 1). Ultrasound-guided abdominocentesis is recommended where possible to avoid inadvertent sampling of the urinary bladder giving a false positive result. If ultrasound examination is unavailable, a four quadrant ‘blind’ abdominocentesis can be performed (Walters, 2003). Concentrations of potassium and creatinine in the abdominal fluid should be compared with serum potassium and creatinine taken at the time of abdominocentesis. Potassium and creatinine are actively excreted in urine, resulting in higher concentrations than in the serum of a healthy animal; it is not helpful to measure urea as, despite being actively excreted in the urine, its smaller molecular weight means that it is rapidly redistributed across the peritoneum, resulting in similar concentrations in the effusion and blood.

Values for confirming a diagnosis of uroabdomen using the ratios of potassium and creatinine between effusion and serum concentrations have been published for dogs and cats, as seen in Table 1 (Aumann et al, 1998; Schmiedt et al, 2001).

Table 1. Reported ratios of potassium and creatinine in abdominal fluid and peripheral blood in dogs and cats

| Abdominal fluid:peripheral blood creatinine | Abdominal fluid:peripheral blood potassium |

|---|---|

| Dogs >2:1 | Dogs >1:4 |

| Cats >2:1 | Cats >1:9 |

A cytological evaluation of the abdominal fluid should be performed to help rule out differential diagnoses and to look for the presence of bacteria or neoplastic cells. Submitting fluid in blood culture medium for a culture and sensitivity panel is also recommended.

Pathophysiology

Urine collection within the abdominal cavity can lead to several pathophysiological consequences, some of which can be life-threatening over a short period of time.

Hyperkalaemia

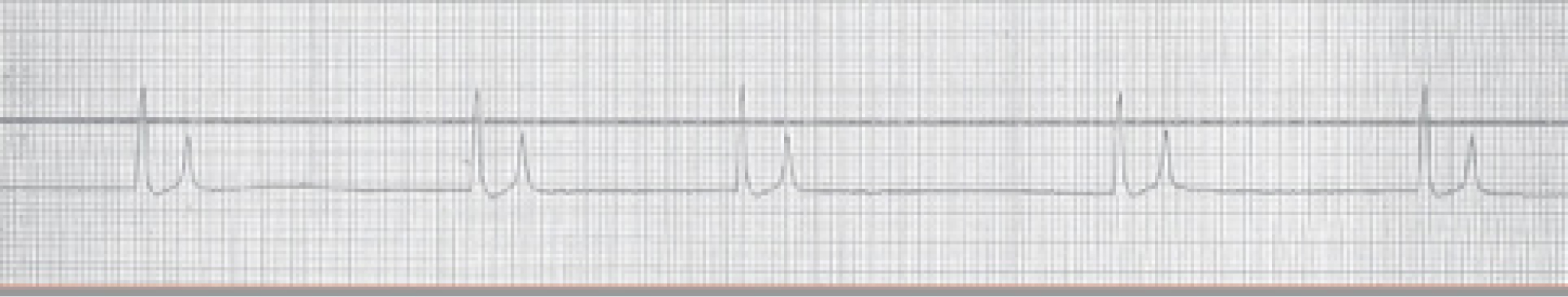

Reabsorption of potassium across the peritoneal membrane from the urine leads to elevated serum potassium concentrations. Hyperkalaemia increases the resting potential of the cell membranes, decreasing the gradient between resting potential and activation threshold, initially leading to increased cell membrane excitability. However, as hyperkalaemia worsens and the resting potential reaches the activation threshold, repolarisation cannot occur resulting in loss of excitability (Drobatz et al, 2018). Cardiomyocytes are particularly sensitive to changes in cell membrane excitability, resulting in slower conduction of the signal and consequent bradycardia and arrythmias. Electrocardiographic changes can be seen, such as tall and tented T waves (Figure 2), reduction in amplitude of P waves, widening of QRS complexes and prolongation of the Q-T interval, and have historically been associated with the severity of hyperkalaemia in an experimental model (Stafford and Bartges, 2013) (Table 2). However, another clinical study did not find an exact relationship between potassium levels and electrocardiographic changes, suggesting other factors such as calcaemia and acidemia could be involved (Tag and Day, 2008).

Table 2. Association between potassium serum levels and electrocardiographic changes

| Potassium levels in serum (mmol/L) | ECG changes |

|---|---|

| ≥5.5–6.5 | Increased T wave amplitude |

| ≥6.6–7.0 | Decreased R wave amplitudeProlonged QRS and P-R intervalsS-T segment depression |

| ≥7.1–8.5 | Decreased P wave amplitude, increased P wave durationProlonged Q-T interval |

| ≥8.6–10.0 | Lack of P waves (atrial standstill)Sinoventricular rhythm |

Circulatory shock

Shock is defined as insufficient oxygen delivery to the tissue, increased oxygen consumption, inability to use the oxygen, or a combination of these (Drobatz et al, 2018). Several types of shock are recognised and can happen simultaneously. Hypovolaemic shock can result from blood loss caused by haemorrhage or fluid loss through vomiting and third-space loss.

Azotaemia

Urea and creatinine excreted through the kidneys are reabsorbed from urine in the abdominal cavity across the peritoneal membrane, leading to azotaemia of post-renal origin. Concurrent acute kidney injury or progressive kidney disease can dramatically worsen the degree of azotaemia.

Dehydration

Urine in the abdominal cavity has increased osmolarity in comparison to plasma and may lead to fluid shift from the extracellular fluid to the third space, resulting in dehydration. Fluid loss can also be exacerbated by vomiting as a result of azotaemia.

Metabolic acidosis

Uraemic acids, reabsorption of hydrogen ions across the peritoneal membrane and lactic acidosis all contribute to metabolic acidosis.

Sepsis

A history of urinary tract infections or bacterial contamination resulting from traumatic injury or a previous surgical procedure can uncommonly lead to septic peritonitis, a severe complication which can result in sepsis.

Pain

Pain is always present in affected animals, originating either from a traumatic event or chemical peritonitis caused by free urine in the abdomen. Appropriate analgesia should always be provided.

Stabilisation

The severity of the clinical condition depends on when the animal presents after the initial injury and the underlying issue. Animals who have undergone trauma or presented some time after initial injury are usually in shock. Oxygen supplementation by face mask to maximise arterial blood oxygen-carrying capacity should be initiated immediately, while organising intravenous access. A mu agonist opioid such as methadone (0.2–0.3mg/kg) should be given to provide analgesia before any procedures. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided as they reduce renal blood flow, potentially worsening azotaemia.

Intravenous fluid resuscitation should be tailored to the animal's condition in order to restore haemodynamic stability. It is therefore important to measure baseline parameters, such as mean arterial blood pressure, heart rate, pulse quality, mucous membrane colour and capillary refill time, and monitor them to evaluate the efficacy of resuscitation. Endpoint goals are a mean arterial blood pressure of 60–70 mmHg, a decrease in heart rate in dogs and improved pulse quality. Cats in shock usually present with a normal heart rate or bradycardia. Therefore, an increase in heart rate is expected when resuscitation is successful.

Isotonic crystalloids such as Hartmann's solution are readily available and represent the first choice in dehydrated animals. An intravenous fluid bolus of 10–20 ml/kg in dogs, and 5–10 ml/kg in cats should be administered over 15 minutes. After the bolus, vital parameters need to be re-evaluated to guide further interventions. If no improvement is achieved, this can be repeated several times up to a total volume of 80–90ml/kg in dogs, and 50–60 ml/kg in cats (Davis et al, 2013).

When hyperkalaemia is detected, or strongly suspected, from clinical presentation and electrocardopgraphic findings, prompt treatment should be initiated, because its progression can cause fatal arrhythmias. Options for management of hyperkalaemia include:

- Calcium gluconate (10% solution) given by slow intravenous injection at a dose of 0.5–1.5 ml/kg (Stafford and Bartges, 2013). Electrocardiographic monitoring should be performed during administration of calcium gluconate, as it can cause bradycardia and arrythmias, in which case administration must be stopped. Calcium gluconate does not reduce serum potassium levels but restores the normal cardiomyocytes excitability and increases the cell membrane activation threshold. Its effect lasts 30–60 minutes and protects the heart from fatal arrythmias, while potassium plasma levels are reduced with other treatments (Drobatz et al, 2018).

- Regular short-acting insulin (0.25–0.5 IU/kg) can be administered intravenously, followed by intravenous glucose at a dose of 1–2g for each unit of insulin administered, to avoid hypoglycaemia (Stafford and Bartges, 2013). Insulin stimulates the activity of the Na+/K+ ATPase-dependent pump, resulting in intracellular shifting of K+. The onset of action is 15 minutes, with maximal activity between 30 and 60 minutes. It is important to remember that because of its hyperosmolarity glucose at 25% or 50% should be diluted with 0.9% saline and administered slowly intravenously. Serial glucose monitoring for the following 12–24 hours is recommended and glucose supplementation required if hypoglycaemia occurs (Drobatz et al, 2018).

- Terbutaline, administered slowly intravenously at a dose of 0.01mg/kg is described (Stafford and Bartges, 2013). It works by stimulating the Na+/K+ ATPase-dependent pump.

- Sodium bicarbonate is considered a last resort in cases of hyperkalaemia refractory to previous treatments. Its use requires serial blood gas analysis to monitor for changes in pH.

- Resolution of azotaemia is in part dependent on its origin. Pre-renal and post-renal azotaemia are treated with intravenous fluid therapy and abdominal drainage to prevent further reabsorption of creatinine across the peritoneal membrane. To drain the abdomen, after clipping and aseptic preparation of the skin, a 21 guage butterfly needle connected to a three-way tap and a large syringe is inserted into the abdomen under ultrasound guidance, and the fluid retrieved from the abdominal cavity. It is mandatory to use a sterile technique to avoid iatrogenic contamination, which can lead to septic peritonitis. When a renal component is involved, resolution is dependent on the residual functional capacity of the kidneys.

Antibiotic treatment should only be started in dogs or cats at a high-risk of infection, or when cytology confirms the presence of intracellular bacteria. Choice of antimicrobial is based on the likelihood of microorganisms involved and the capacity of the molecule to reach the affected tissues. The therapy can be adjusted according to the culture and sensitivity results.

Urinary diversion techniques

Once clinical stabilisation is achieved, the focus can move to preventing further accumulation of urine within the abdominal cavity. Depending on the site of leakage, different techniques can be used. General anaesthesia is not always required, and it is ideal to avoid this where possible during the early stages of treatment, but local anaesthetic techniques are an important resource and will be discussed.

Urethral catheterisation

Whenever possible, retrograde placement of a urethral catheter should be achieved early in the course of stabilisation. Keeping the bladder decompressed and bypassing the urethra are helpful in the case of bladder or urethral tears to reduce extra-luminal leakage of urine and to encourage healing of the traumatised urinary tissue by second intention. Small tears can indeed heal without need for surgical correction. The indwelling catheterisation should last until surgical repair is performed or for a sufficient time to allow healing of the tissues, with a minimum of 5 days according to published studies (Degner and Walshaw, 1996; Meige et al, 2008)

Cystostomy tube

When urine is leaking from the urethra and placing a urethral catheter is not possible, consideration must be given to how to reduce urine leakage into the abdomen in the time between presentation and surgical repair or urinary diversion. Repeated cystocentesis can be effective but multiple punctures are required, carrying the risk of iatrogenic complications such as leakage of urine, damage to the bladder or other organs (Buckley et al, 2009) and bacterial contamination of the abdomen (Specht et al, 2002). Placement of a cystostomy tube is an alternative, which can be achieved via a midline laparotomy, but minimally invasive techniques have been described recently. A pigtail cystostomy tube can be placed with ultrasound guidance (Culler et al, 2019), or via a minimally invasive inguinal approach (Bray et al, 2009). It is worth noting that complications occurring secondarily to cystostomy tube placement are common. An incidence of 49% was reported in the largest study to date (Beck et al, 2007). In that study, the most frequent major complication was inadvertent removal of cystostomy tube, although only one animal developed uroabdomen as a consequence. Urinary leakage and inflammation around the tube were the most common minor complications.

Peritoneal catheter

Use of a peritoneal catheter can be considered as part of the initial stabilisation. This also has the advantage of allowing peritoneal dialysis to be performed in the case of acute kidney injury (Ross and Labato, 2013). Placement of a dedicated peritoneal catheter is ideal, where available. However, the use of Jackson-Pratt drains and trocar chest drains (connected to a closed collection system) for temporary peritoneal drainage during stabilisation has also been described (Ross and Labato, 2013). Ultrasound guidance during placement can be invaluable.

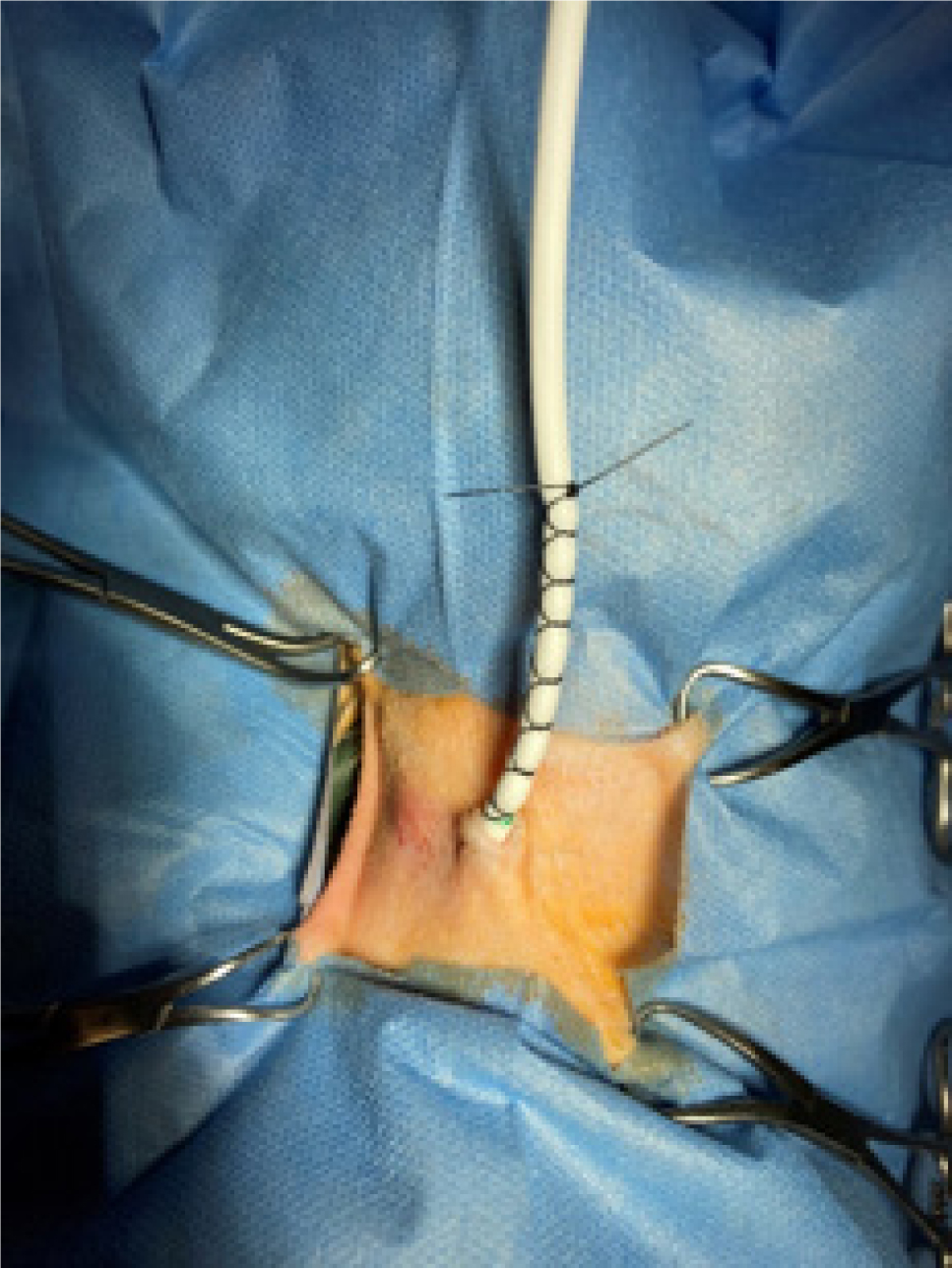

Drains must be placed aseptically, including clipping and preparing the skin, using sterile gloves and equipment. Readers are advised to familiarise themselves with the manufacturers' guidance for placing each of the commonly used types of drain. Once placed, most types of drain are secured to the skin by placing purse-string sutures at the entry site into the skin, then a finger-trap pattern on the drain tubing itself (Figure 3). Daily management of the drain is required to assess its patency because mechanical obstruction is commonly reported (Cooper and Labato, 2011). It is essential to maintain sterile technique during daily assessment to minimise the risk of contaminating the tubing and collection system, which can lead to peritonitis (Dzyban et al, 2000).

Anaesthetic considerations

Local anaesthesia techniques and mild sedation are usually preferred to general anaesthesia in unstable animals, because of the increased risk associated with general anaesthesia in systemically compromised dogs and cats.

Providing analgesia by the use of a pure mu agonist such as methadone at a dosage of 0.2–0.3 mg/kg is often enough to allow stabilisation procedures, such as placement of a urinary catheter.

If a more invasive procedure has to be performed, such as placement of a cystostomy tube or peritoneal catheter, the tissues around the planned incision site can be injected with a local anaesthetic, such as lidocaine or bupivacaine.

Locoregional techniques such as epidural anaesthesia can be considered, but contraindications to their use include hypotension, infection of the site of injection, neurological deficits, disruption of normal anatomy at the injection site, and sepsis, all of which are commonly encountered in animals with uroabdomen.

When general anaesthesia is required, the anaesthetic protocol should be carefully considered and the time of anaesthesia kept as short as possible. Pre-medication other than an opioid is not usually necessary; alpha-2 adrenoreceptor agonists (such as medetomidine, dexmedetomidine and xylazine) should be avoided because of the increased risks of brady-arrythmias in hyperkalemic animals and the negative effect on cardiac output. Acepromazine is also not ideal in haemodynamically unstable cases because of its vasodilative effect which can worsen the hypotension.

As an induction agent, alfaxalone has less impact on cardiac output compared to propofol and it can be titrated to effect when given intravenously. If alfaxalone is not available, a slow induction with propofol titrated to effect can be used. The lowest effective concentration of volatile agents (isoflurane, sevoflurane) to maintain adequate anaesthesia should be used, because of the vasodilation these drugs can cause.

Constant monitoring of mean arterial blood pressure, electrocardiographic trace and oxygen saturation should continue throughout anaesthesia and also during the recovery phase, which has been shown to be when most fatalities occur (Brodbelt et al, 2008).

Prognosis

Prognosis is dependent on the severity and location of the urinary tract rupture, and the presence of concurrent comorbidities. A mortality rate of 21% was seen in a retrospective study of dogs with uroabdomen (Grimes et al, 2018), whereas a mortality rate of 41% has been reported in cats (Aumann et al, 1998).

Conclusions

Early diagnosis and aggressive treatment of life-threatening conditions such as shock and hyperkalaemia are the mainstay of initial management of canine and feline uroabdomen. Once the patient is more stable, diagnostics are required to identify the source of leakage and provide appropriate treatment. Discussion of definitive treatment is beyond the scope of this article.

KEY POINTS

- Uroabdomen should always be considered in the differential diagnoses after an abdominal trauma or in cats and dogs presenting in shock with a known history of urinary tract disease.

- Collecting and analysing any free abdominal fluid is essential to achieve a diagnosis.

- Treating shock and hyperkalaemia must be the priority, as they can be life-threatening over a short period of time.

- Analgesia and local anaesthetic techniques are better options than general anaesthesia in unstable animals.

- Stabilising animals' conditions and providing urinary diversion are the priority before considering definitive treatment options.