In recent years the word ‘boundary’ has become a popular buzzword in our society. However, this concept is more than just the latest popular phrase, as healthy personal boundaries are important for keeping us in healthy relationships with our clients, colleagues, our places of employment, our friends and family. This is the first instalment of two articles, which explore setting and maintaining healthy personal boundaries as a veterinary professional at work and beyond. The information draws from evidence-based practice in the disciplines of educational and clinical psychology (Kohn, 1993; Rosenberg, 2015), psychotherapy (Cloud, and Townsend, 1992), cognitive behavioural therapy (Tawab, 2021), life coaching (Levin, 2020; Wise, 2020), social work (Brown, 2015; 2018) and human healthcare (Puder, 2018; 2019; Maté, 2019) and has been applied to the veterinary profession. The author has included what they have found useful in their understanding of boundaries and has occasionally used anecdotes and personal examples to illustrate an academic point.

This article will discuss what personal boundaries are, why they are important and why veterinary professionals may struggle to instigate them. The next article in this series will consider how to set and maintain healthy boundaries and how they may benefit us in veterinary practice.

What is a personal boundary?

Personal boundaries are the emotional and behavioural metaphorical walls that we need to maintain healthy relationships with ourselves, other people and our environment. We need to set a boundary when our physical or psychological safety is threatened (Puder, 2018). Boundaries are unique to us based on our own personality, ethics, values, experiences, feelings and needs.

It can be useful to use the metaphor of property lines around our house. In this case, we have a very clear idea of what we own and what we are in control of (Cloud and Townsend, 1992). We can see where our metaphorical property starts and where our neighbours' begins. Our fence denotes a clear outline of what is our responsibility to take care of and what is our neighbours' responsibility. When we know where our boundary line is, it allows us the freedom to do with our house and garden as we wish and it gives us power over ourselves and our lives. Our fences keep us safe by allowing us to keep positive things in and destructive things out. When good things are on the outside, we can choose to open our gates and let them in. We need our property lines to be clearly visible to other people so that they do not trespass across them. For example, the relationships we have with our friends and family can be a positive influence in our lives, but if they repeatedly ask us veterinary-related questions when we are not working and need to rest, this may become an overwhelming or destructive influence. This is when it is important to erect a clear metaphorical fence and let people know what we find acceptable, to protect both us and the continuing relationship.

How we treat and care for our metaphorical property sets an example to others; if we allow rubbish to accumulate in our front garden, people may feel that fly tipping is acceptable. After all, who is going to notice if the pile of debris gets a little bit bigger? How we treat what is ours sets an example to others as to how we want to be treated (Brown, 2015). For example, if a client is repeatedly late for appointments and we do not tell them that this is unacceptable, this behaviour will likely continue and the client will not learn to value our time. How this feedback is provided may come under practice policy, or it may be at the discretion of the attending clinician, who is now running late consultations, to instigate a personal boundary.

Some examples of things we are responsible for and need to instigate boundaries to protect are:

- Physical boundaries: our body

- Material/resource boundaries: our time, money, influence, education, qualifications, achievements and energy levels

- Mental/intellectual boundaries: our thoughts, opinions, preferences, life choices, ethics, morals, values, priorities, experiences, interests and ambitions

- Emotional boundaries: our needs, emotions and feelings

- Behavioural boundaries: our actions.

Where our boundaries are set and how they are executed does not involve anyone else (Tawab, 2021). Boundaries are not a demand, a threat or an ultimatum. They are not a means to control the behaviour of another person; their failure to comply does not result in punishment or disciplinary action.

The natural consequences of instigating our boundaries do not constitute active punishment. The following are not examples of personal boundaries, because punishment may occur if they are violated:

- The law

- Practice policy

- Contractual terms of employment

- Standard operating protocols

- The Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons' (2012) code of professional conduct

- Teaching instruction

- ‘The rules’ (written or unwritten, as in workplace culture)

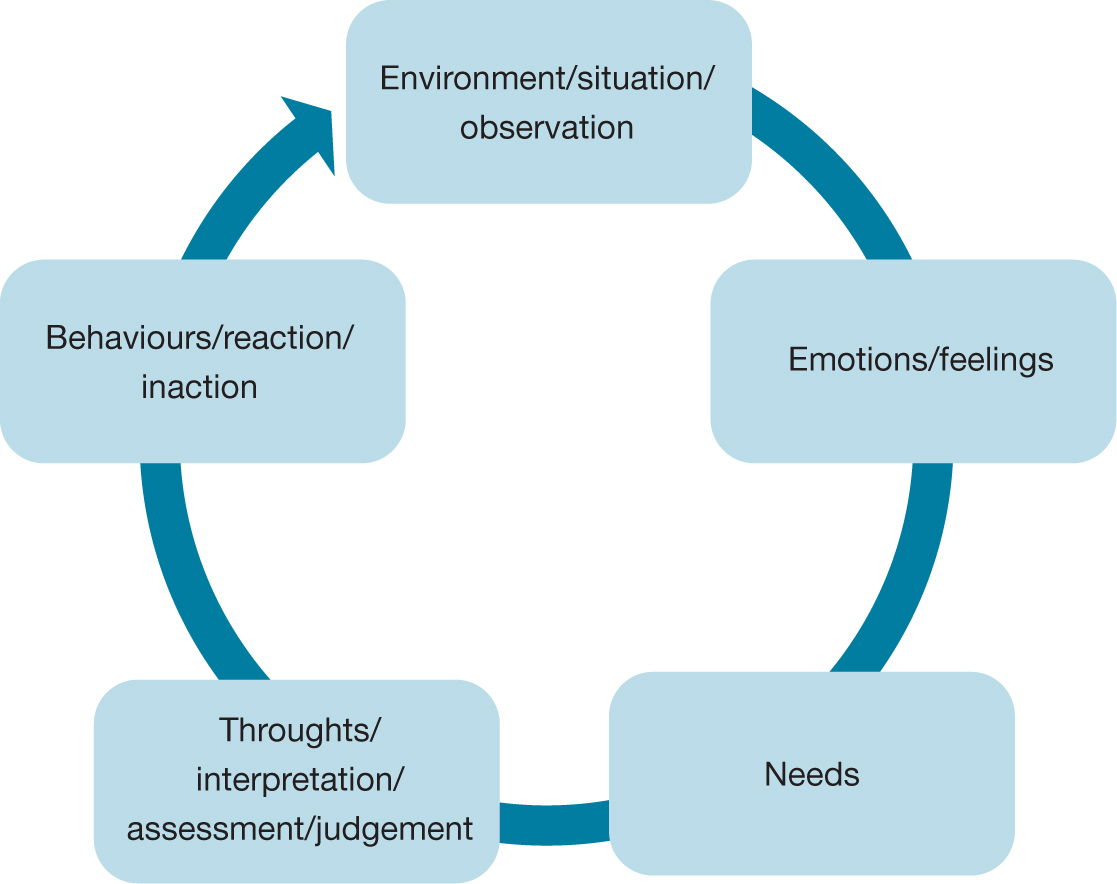

Instigating boundaries does not necessarily mean that we can avoid conflict and discomfort (Rosenberg, 2015). Negative emotions are normal and if we acknowledge and explore these, they can provide useful information about our situation and environment, as well as our needs, thoughts and reactions (Figure 1). They may form a protective function or inform us when we are out of our ‘comfort zone’.

Personal growth and academic learning will inherently lead to a degree of discomfort and may involve pushing our personal boundaries (Brown, 2018). Therefore, avoiding these feelings will not keep us in a healthy relationship with ourselves. However, we need to instigate healthy boundaries to ensure that our growth and learning follow a sustainable trajectory.

How do I know if I have a problem setting personal boundaries?

Acknowledging that you have a problem with setting boundaries requires self-reflection (Tawab, 2021). If you relate to any of the following this may be an area of personal growth for you to consider:

- You find yourself in situations in which you are not psychologically or physically safe

- You agree to do things that you are uncomfortable with, or do not have time to do. You give a non-genuine ‘yes’

- You place other people's comfort ahead of your own needs

- You find confronting other people difficult when problems arise

- You may find long-term jobs depressing and struggle to maintain healthy work relationships. You may frequently change jobs.

Why do we need boundaries?

If a situation does not meet our needs for a prolonged period of time, then it becomes unsustainable and has an impact on both our physical and mental health. This can be experienced as chronic stress resulting in depression, especially if anger is turned inward, or bodily pain from outwardly expressed physical tension (Maté, 2019). Eventually we may ‘act out’ to alleviate this pain, often resulting in drastic behaviour such as leaving a job or the veterinary profession altogether.

Alternatively, we may experience burnout, where we can no longer engage mentally or physically (Nagoski and Nagoski, 2020). When we set and maintain boundaries to ensure that our needs are met, we have more joy, love and energy to give to others (Brown, 2015).

The need for boundaries and living ‘BIG’

I was 38 years old when I realised I had a problem with setting boundaries. The more I explored the topic, the more I understood its importance to my colleagues in the veterinary profession. This personal journey with boundaries did not start with the premise that I was worthy of the self-protection afforded by setting boundaries, but instead the realisation that if I was going to continue to be empathetic and compassionate towards others, then I needed to do so in a sustainable way.

Using grounded theory research techniques, compassion and shame researcher Dr Brené Brown (2015) formulated the concept of ‘Living BIG’ with boundaries, integrity and generosity. In order to extend empathy and compassion, we need to instigate boundaries to ensure that we acting within our integrity. It is unsustainable to make generous assumptions of others when they are hurting us.

What boundaries (B) do I need to put in place so that I can work from a place of integrity (I) and extend the most generous (G) interpretations of the intentions, words and actions of others?

‘Integrity is choosing courage over comfort, choosing what is right over what is fun, fast and easy; and choosing to practice our values, rather than simply professing them’ (Brown, 2015).

Why is it hard to create boundaries?

Creating boundaries can be difficult for multiple reasons. First, we may not know what boundaries look like. They may not have been modelled in our family, or by societal expectations. We may be so disconnected from our needs that we are unaware when we need to instigate a protective boundary at all (Levin, 2020). For example, society often expects women to be responsible for caregiving roles. Many mothers in the veterinary profession may also believe this and may take on the bulk of childcare, while also working. It may not occur to them they can instigate some protective boundaries against the resulting mental load, to minimise the feelings of being overwhelmed. Over time, external expectations can become internalised and form self-limiting shadow or false beliefs. Some beliefs may help us to navigate growing up, but may no longer serve us as adults. Understanding the beliefs we have that hold us back requires self-reflection.

Secondly, language can perpetuate a denial of personal responsibility. Phrases such as ‘you made me do/feel/say’ are what clinical psychologist Marshall Rosenberg (2015) describes as ‘life alienating language’. What others say and do may be the stimulus for us to feel in a given way, but they are not the primary cause. Correlation does not equal causation.

For example, when a client does not attend their consultation, we may feel:

- Relieved because we are overbooked

- Angry because there have been other missed appointments

- Concerned if we like the client and they are usually punctual.

When we attribute our emotions to the actions of others, we remain unaware that we are reacting to our own needs being frustrated. If the other person subsequently believes they are responsible for our emotions, they may change their behaviour to alleviate our discomfort. This may appear positive and caring but the behavioural changes instigated are not always motivated by love and a desire to contribute to our wellbeing, but instead to avoid feeling guilt or shame, unconsciously motivated by fear, and this ‘guilt trip’ can lead to resentment (Rosenberg, 2015).

Why do veterinary professionals struggle to set boundaries?

In January 2022, the Facebook group ‘Not One More Vet’ (https://www.facebook.com/groups/NOMVet/about/) received multiple posts about the new Disney film ‘Encanto’, with veterinary professionals identifying very strongly with the character of Luisa Madrigal. Despite being very stressed, Luisa tries to maintain her image as a powerful and reliable individual who can shoulder the burdens of everybody around her. It is clear that Luisa's self-worth is reliant on her ability to help others when she sings ‘I'm pretty sure I'm worthless if I can't be of service’. When her mental health suffers from the internalised ‘surface pressure’, Luisa begins to lose her magical powers of physical strength. Initially Luisa fails to set limits or create a work–life balance. As the film progresses, she learns to make decisions about where she channels her energy, to accept help, to free up time for joy and relaxation and in doing, so she learns to live more sustainably.

Dr Cari Wise (2020), founder of ‘The Joyful DVM’, identifies three personality traits which make veterinary professionals more vulnerable to poor boundary setting. There may be overlap between these personality traits:

- Compassion-driven and empathetic personalities

- Perfectionism

- Hyper-responsibility or people pleasing.

While this list is not exclusive, it provides a good framework to start the conversation.

Compassion-driven and empathetic personalities

The majority of veterinary professionals are empathetic and compassionate people. People who identify as being compassionate often feel ashamed when they are unable to alleviate the suffering of others. They may hold shadow beliefs that being compassionate means they will always sacrifice their own needs for others, that being selfish (considering oneself) is ‘bad’ and that it is their moral duty to be compassionate. This may prevent them from drawing self-protective boundaries.

It is important to consider what empathy and compassion actually are. Empathy is a multidimensional construct comprising cognitive (perspective taking), affective (a shared emotional state) and behavioural components (Box 1) (Clark et al, 2019). It is the ability to put yourself in someone else's position and to see the world from their perspective. We act compassionately when we act to alleviate another's suffering. Empathy can result in the reduction of conflict and the formation of powerful emotional bonds.

Box 1.The definitions of empathy and compassion.Cognitive empathyCognitive empathy, or perspective taking, is the process of understanding another's situation, emotions and motivations through our own mental processes, acquisition of knowledge and understanding. Perspective taking allows us to see similarities in our behaviour patterns and rehumanises people, which can reduce interpersonal aggression. An example would be, ‘I see what you mean’.Affective empathyAffective empathy involves a shared emotional experience and occurs when we experience an affective state that is congruent with another person. Affective empathy uses the mirror neuron system in the brain and can result in the formation of powerful emotional relationships. An example would be,‘I feel your pain’.Behavioural empathyBehavioural empathy occurs when you behaviourally demonstrate that you have understood (cognitive empathy) or shared in (affective empathy) how another person experiences their reality through verbal and non-verbal behaviours. Examples would be, ‘I am going to tell you that I see what you mean/that I feel your emotion’, or ‘I am going to do something (speak/exhibit supportive body language) to change/engage in the situation’.

Compassion involves an observer assessing someone else's suffering and feeling concern for their wellbeing. This evaluation results in a behavioural response to help alleviate the suffering person's situation.

In empathetic concern, the observer and sufferer are connected by a shared understanding of an emotional state. Sympathy does not involve the observer and sufferer experiencing the same emotional state and this lack of understanding and connection can be felt as shame by the sufferer. Both empathetic concern and sympathy are motivators for compassion:

- Empathetic concern: ‘I know that feeling and it sounds like you are having a really awful time’

- Sympathy: ‘That wouldn't happen to me but that sounds really awful for you’

- Compassion: ‘I feel motivated to help change this situation’

Empathy is a multidimensional construct comprising cognitive, affective and behavioural components. Both empathy and sympathy can motivate people to be compassionate. These processes are neurologically disguisable and involve different parts of the brain (Clark et al, 2019; Puder, 2019).

People who are high in afferent empathy may find boundary setting hard for several reasons. First, they may literally feel the other person's emotions. There is neuroscientific evidence that observing another person's pain activates the areas of the observer's brain responsible for pain via the mirror neuron system (Singer and Lamm, 2009). Sometimes people who are high in afferent empathy are unaware of which emotions they own and which belong to an external source (De Vignemont and Singer, 2006). For example, someone might feel very anxious about an atmosphere at work, despite nothing stressful having happened to them personally that day. The anxiety is coming from an external source and does not belong to the observer but is still felt emotionally.

People high in afferent empathy may have codependent tendencies or struggle to identify their own feelings and needs, thus look for an external source to emotionally regulate them (Levin, 2020). A person exhibiting co-dependence will ascertain the mood of others before deciding what is acceptable and safe for them to feel and do. For example, many people will check to see what mood the boss is in before settling in for a shift. The resulting behaviour is about what the external source feels and needs, not what the co-dependant needs: this results in a strong compulsion to control situations and the behaviour of others to ensure safety. Because people exhibiting co-dependency struggle to identify their own feelings and needs, they find it difficult to instigate boundaries.

Cognitive empathy (perspective taking) is a learned skill and can be developed and improved upon with continued practice and experience (Puder, 2019). Learning to cognitively empathise with our colleagues and clients improves these relationships. People who practice cognitive empathy often find it easier to draw boundaries than those who are high in afferent empathy because they are not physically feeling the emotions of others and are more cognitively aware of their own emotions and needs. Well-regulated empathy is a skill linked to positive outcomes in healthcare and moral achievements, however it can be a ‘risky strength’ (Tone and Tully, 2014). When we empathise with others without consideration for ourselves, this can impact our mental health.

Perfectionistic personalities

Given the high academic admission requirements of veterinary schools, it is unsurprising that many veterinarians struggle with perfectionism. Educational psychologist Alfie Kohn (1993) reported that a system of measuring people by grades and external rewards hinders a growth mindset and creates perfectionistic traits.

I remember believing that if I could be perfect, then there would be no reason for my application to veterinary school to be rejected. Since I was accepted, the belief that ‘perfection makes you safe from rejection’ was then perpetuated. Being far from the ‘perfect’ veterinary student was subsequently a huge source of chronic stress and subsequently, I often disengaged. In this case, I interpreted perfection as achieving high grades in exams and did not consider other skills such as research, practical or communication skills, which I rely on daily in clinical practice.

Perfectionism is characterised by Hill (2020) as:

- Excessively high standards (without consideration of confounding variables). This is not the same as striving for growth or high clinical standards

- Overly critical evaluations of behaviour (with resulting blame and shame).

Perfectionism is a multidimensional construct incorporating three aspects (Hill, 2020):

- Self-orientated: demanding perfection of yourself

- Other-orientated: demanding perfection from others

- Socially prescribed perfectionism: the belief that other people or society demand perfection from you.

There is considerable overlap between these areas. As veterinary professionals, the internalised pressure of perfectionism can often drive our behaviour and result in difficulty drawing boundaries when we fear not living up to the image of perfection outlined by ourselves, our colleagues and the general public.

Imposter syndrome is a form of perfectionism reported in our counterparts in human medicine, especially so by women (Freeman and Peisah, 2021). Imposter syndrome is perpetuated and intensified by ‘blame and shame’ cultures and has ramifications for leadership roles and career progression. It affects how we handle clinical challenges, poor patient outcomes, complaints and feedback. Imposter syndrome occurs when a person perceives themselves as not being good enough, of being an imposter, because of a failure to meet self-imposed perfectionistic standards. This occurs despite external evidence to the contrary, such as outstanding academic and professional accomplishments, as the sufferer minimises these achievements, often holding the belief that ‘if I can do it anyone can.’ This thought not only results in low confidence and self-esteem, but may lead to anxiety, depression and burnout, which has been linked to an increased risk of substance abuse and alcoholism. The resulting behaviour often involves excessive diligence and hard work, motivated by a fear of failure or self-perceived incompetence being exposed. When we hold the belief that we are an imposter, this may prevent us from setting self-protective boundaries because we fear this will result in us ‘being found out’ about not living up to our self-imposed perfectionistic standards.

People-pleasers and hyper-responsibility

People pleasing is a psychological characteristic defined by approval-motivated behaviour. People pleasers are nice, likable, kind people who are ‘over-givers’ or avoid conflict. The perceived need for approval can result in an inability to identify one's own feelings and needs, or instigate protective boundaries. There are three types of people pleasing: cognitive people pleasing, behavioural people pleasing and emotionally avoidant people pleasing (Braiker, 2002).

Cognitive people pleasing

Cognitive people pleasers believe that they need to be liked (Braiker, 2002). They believe the needs of others should take precedence over their own and are perfectionistic in their pursuit of this. They may have an inflated sense of responsibility (hyper-responsibility) and believe they have more control (and so more responsibility) over their environment than they actually do. Consequently, they believe it is always their job to help and subsequently take on blame or feel ashamed when things go wrong, without holding others accountable for their part in a situation. They may believe that being nice, helpful and needed will protect them from rejection and hurtful treatment by others, and gain them acceptance and safety. As veterinary professionals we often have the notion that we are responsible for everything, so it can be useful to refer to the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons' (2012) code of professional conduct to clarify exactly what we are responsible for. We are not personally responsible for the welfare of every single animal and the code states that the ‘responsibility for the welfare of an animal ultimately rests with the owner, keeper or carer’. We are also not responsible for ensuring that the needs of the general public are met.

Behavioural people pleasing

Behavioural people pleasing is defined by a habitual, sometimes compulsive drive to take care of other people at the expense of the ones own needs (Braiker, 2002). They rarely say ‘no’, rarely delegate and often become overcommitted and overwhelmed. Despite the negative impact on mental and physical health, these behaviours are perpetuated by an excessive, almost addictive need for the dopamine response achieved from external approval.

Emotionally avoidant people pleasing

Emotionally avoidant people pleasing is defined by avoidance of fearful, uncomfortable emotions (Braiker, 2002). The possibility of anger or confrontations produces stress, anxiety and possibly the reliving of trauma. This behaviour focuses on avoiding anger, conflict and confrontation and often results in an individual not upholding their boundaries and relinquishing control to people who dominate through bullying, intimidation and manipulation. This is an acquired behaviour, often an adaptation from childhood.

Conclusions

A personal boundary is a metaphorical emotional or behavioural wall, marking where we end and another person begins. Our bodies, resources, intellect, emotions and behaviour are our responsibility to care for and protect, all lying within our boundary lines. Where we draw boundaries is specific to us based on our ethics, values, priorities, experiences, feelings and needs. We need to draw boundaries to ensure our physical and psychological safety. Veterinary professionals may struggle with setting boundaries because they may be driven by compassion or empathy or have perfectionistic or people-pleasing tendencies.

KEY POINTS

- Healthy personal boundaries allow us to maintain healthy relationships.

- We need to draw personal boundaries to protect our body, our resources, our intellect, our emotions and our behaviour.

- We need to draw boundaries to ensure our physical and psychological safety.

- Our boundaries are specific to us based on our own personality, ethics, values, priorities, life experiences, feelings and needs.

- Veterinary professionals may struggle to set boundaries because they may be compassion- or empathy-driven personalities, or struggle with perfectionism or people pleasing.