Cats are a hugely popular domestic pet, with around 10.7–12.2 million cats owned in the UK and around 27% of UK households estimated to own at least one cat (PDSA, 2021; Cats Protection, 2023). Many owners share close and strong human–animal bonds with their cats, which benefit these owners by measurable reductions in negative moods, anxiety and depression (Rieger and Turner, 1999; Turner and Rieger, 2001). However, it is important that cats also benefit from their role in this human-animal partnership; therefore, owners and keepers also have legal and ethical responsibilities to care for their cats' physical and mental health (Gray and Fordyce, 2020). It is critical for owners to understand the most common medical conditions that may affect their animals, in order to fulfill their cargiving roles (Overgaauw et al, 2020). A key prerequisite for this is veterinary professionals having ready access to this information so they can share it with their clients. For example, when veterinary teams raise awareness with cat owners that disorders such as dental disease and obesity are common, yet largely preventable diseases, this can support owners to be more proactive in their cat's healthcare by working closely with their veterinary practice to reduce welfare impacts of these conditions (Wall et al, 2019). As well as knowing which disorders are the most common, an understanding of how sex and age affect the risk of common disoorders should also assist owners to improve their decisions, first when choosing a cat and later on, during ownership (Sordo et al, 2020). As an example, young male cats are reported to have higher risk of road traffic accidents so owners living on busy roads might choose to acquire an older cat or a female cat to reduce this risk (McDonald et al, 2017).

Cats experience varying levels of risk for developing differing disorders as they age (O'Neill et al, 2021). Better understanding of age-related disorder risk can allow for more targeted prevention, diagnosis and clinical management (Niccoli and Partridge, 2012). Quality of life can be challenging for owners to interpret accurately in cats, especially for conditions that develop gradually in older cats. For example, osteoarthritis is reportedly a common problem in older cats; however, the main clinical signs are not overt lameness but behavioural and lifestyle changes which owners often interpret as just ‘old age’ (Clarke and Bennett, 2006; Bennett et al, 2012; O'Neill et al, 2014). Hence, improved awareness by owners of age-related disorders such as osteoarthritis could promote enhanced access to veterinary care and help the recognition and alleviation of pain (Benito et al, 2013).

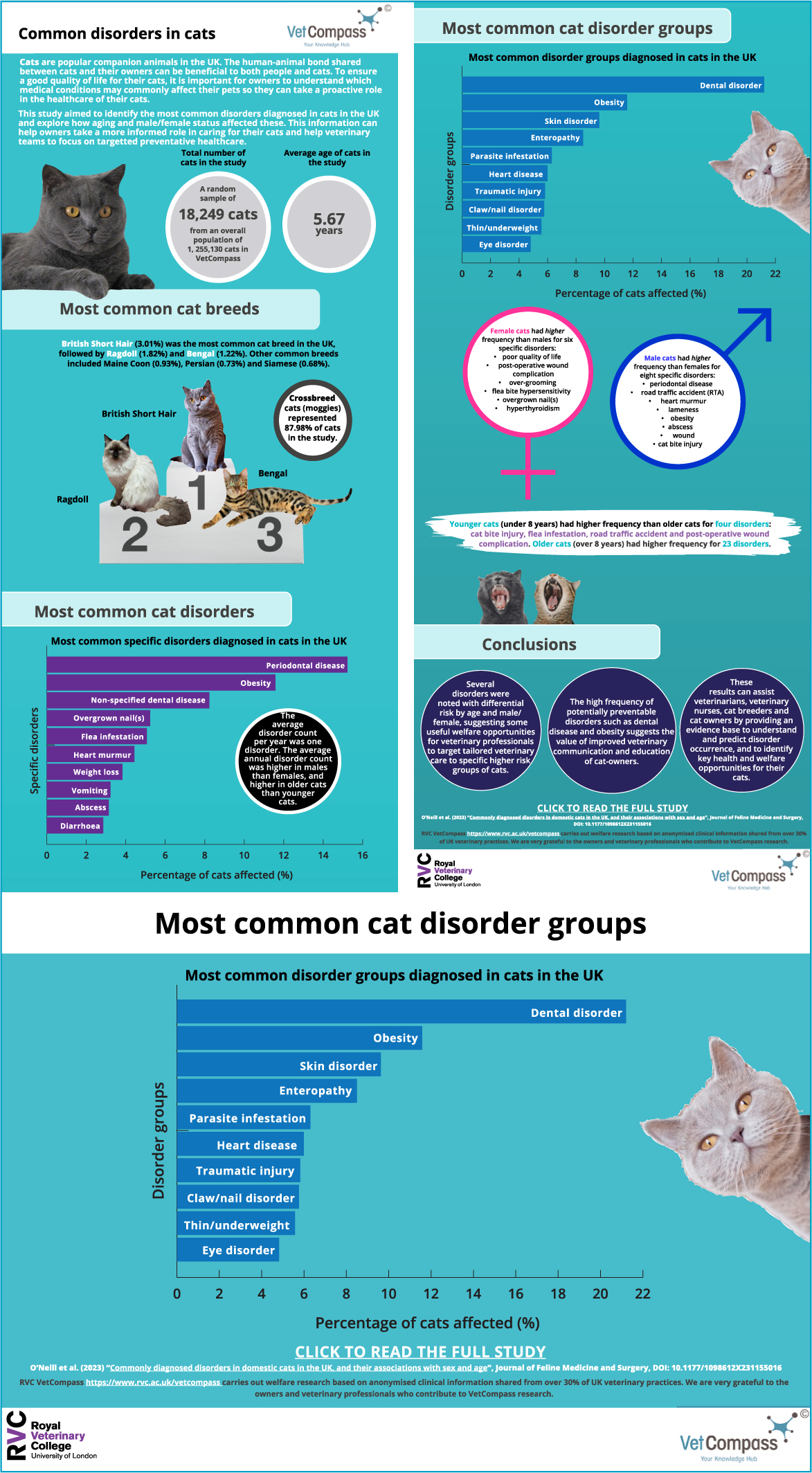

Against this background, this article summarises the findings of a recent paper that reported the prevalence of common disorders in cats under primary veterinary care during 2019 in the UK (O'Neill et al, 2023). The paper also explored associations between common disorders with sex and age. Based on this information from the general population of cats attending primary care in the UK, several opportunities were highlighted for veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses to engage more effectively with owners and focus on targeted healthcare approaches, with particular emphasis on improved dental health and weight control.

Methods

The study population included all cats under primary veterinary care at clinics participating in the VetCompass Programme during 2019. VetCompass is an epidemiological research programme that collates and investigates data from primary care veterinary practices across the UK (VetCompass, 2023). The study used a retrospective cohort study design to estimate the one-year (2019) period prevalence of the most commonly diagnosed disorders.

A random sample of cats was selected and the clinical records were manually reviewed to extract the most definitive diagnoses recorded for all disorders that existed during 2019 (O'Neill et al, 2021). Disorder events were followed over time in the cohort data source and were coded to the most precise diagnostic or descriptive term available in the VeNom coding system (VeNom Coding Group, 2022). Disorders described within the clinical notes using presenting sign terms (for example, ‘vomiting’ or ‘vomiting and diarrhoea’), but without a formally recorded clinical diagnostic term, were included using the first sign listed (such as vomiting). Data on elective (e.g. neutering) or prophylactic (e.g. vaccination) clinical events themselves were not recorded.

Breed descriptive information entered by the participating practices was cleaned and mapped to a VetCompass breed list derived and extended from the VeNom Coding breed list (VeNom Coding Group, 2022). Adult bodyweight was defined as the average (mean) of all bodyweight (kg) values recorded for each cat after reaching 9 months old. Age (years) was defined at December 31, 2019. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata Version 16 (Stata Corporation). One-year period prevalence values with 95% confidence interval described the probability of diagnosis at least once during 2019. Confidence interval estimates were derived from standard errors based on approximation to the binomial distribution (Kirkwood and Sterne, 2003). The median age (years) across all affected animals was reported. Prevalence values were reported overall and separately for females and males. Univariable comparisons used the Chi-squared test to compare categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test to compare continuous variables (Kirkwood and Sterne, 2003). Statistical significance was set at the 5% level.

Results

Demography

The study included a random sample of 18 249 (1.45%) cats from 1 255 130 cats under veterinary care in the UK during 2019. The sample included 9 141 (50.09%) females and 8 944 (49.01%) males. The median age of the cats overall was 5.67 years (interquartile range [IQR] 2.39–10.32, range 0.03–23.90). Females (5.76 years, IQR 2.48–10.63, range 0.03–23.90) were statistically younger than males (5.59 years, IQR 2.33–9.94, range 0.05–23.26) (P<0.001). The median adult body weight overall was 5.50kg (IQR 3.99–7.40, range 1.50–15.00). Body weight did not differ statistically between females (5.49kg, IQR 3.95–7.39, range 1.50–15.00) and males (5.50kg, IQR 4.00–7.43, range 1.50–15.00) (P=0.449). Of cats with breed information recorded, 12.02% (n=2164) were classified as purebred. The most common pure breeds were British Short Hair (n=542, 3.01%), Ragdoll (n=328, 1.82%), Bengal (n=219, 1.22%), Maine Coon (n=168, 0.93%), Persian (n=131, 0.73%) and Siamese (n=123, 0.68%), along with 15 841 (87.98%) crossbred cats.

Disorder occurrence

From the random sample of 18 249 cats, 12 042 (65.99%) had at least one disorder recorded during 2019. Male cats (67.55%) were statistically more likely to have at least one disorder recorded than females (64.60%) (P<0.001). The median age of cats with at least one disorder recorded (6.88 years, IQR 3.05–11.48, range 0.03–23.90) was older than for cats that had no disorders recorded (3.77 years, IQR 1.63–7.64, 0.03–23.80) (P<0.001). There were 25 891 unique disorder events recorded during 2019 among the 18 249 study cats, encompassing 641 distinct precise-level disorder terms (Table 1). The prevalence differed between the sexes for 14 (46.67%) of the 30 most common precise-level disorders, with females showing higher prevalence for six disorders and males showing higher prevalence for eight disorders (Table 1). Among the 30 most common precise-level disorders, the median age varied from 1.67 years for post-operative wound complication to 16.78 years for poor quality of life, and the prevalence differed between the younger (<8 years) and older (≥8 years) cats for 27 (90.00%) disorders. Younger cats had higher prevalence than older cats for four disorders while older cats had higher prevalence for 23 disorders (Table 1).

Table 1. Prevalence of the 30 most common disorders in cats.

| Disorder | No. | Overall % | 95 % CI* | Female % | Male % | Female: male risk ratio | Sex P-value | Younger % | Older % | Younger: older risk ratio | Age P-value | Median age (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Periodontal disease | 2780 | 15.23 | 14.72-15.76 | 14.75 | 15.82 | 0.93 | 0.045 | 9.64 | 25.3 | 0.38 | < 0.001 | 9.47 |

| Obesity | 2114 | 11.58 | 11.12-12.06 | 10.85 | 12.43 | 0.87 | 0.001 | 10.95 | 13.09 | 0.84 | < 0.001 | 6.83 |

| Dental disease | 1502 | 8.23 | 7.84-8.64 | 8.17 | 8.31 | 0.98 | 0.741 | 5.80 | 12.71 | 0.46 | < 0.001 | 8.64 |

| Overgrown nail(s) | 954 | 5.23 | 4.91-5.56 | 5.87 | 4.61 | 1.27 | < 0.001 | 4.63 | 6.37 | 0.73 | < 0.001 | 6.79 |

| Flea infestation | 926 | 5.07 | 4.76-5.40 | 4.92 | 5.29 | 0.93 | 0.264 | 5.76 | 3.98 | 1.45 | < 0.001 | 3.62 |

| Heart murmur | 811 | 4.44 | 4.15-4.75 | 4.06 | 4.85 | 0.84 | 0.01 | 2.21 | 8.46 | 0.26 | < 0.001 | 11.67 |

| Weight loss | 699 | 3.83 | 3.56-4.12 | 4.05 | 3.63 | 1.12 | 0.148 | 1.18 | 8.5 | 0.14 | < 0.001 | 13.43 |

| Vomiting | 589 | 3.23 | 2.98-3.49 | 3.41 | 3.06 | 1.11 | 0.184 | 2.49 | 4.54 | 0.55 | < 0.001 | 8.26 |

| Abscess | 573 | 3.14 | 2.89-3.40 | 1.76 | 4.55 | 0.39 | < 0.001 | 2.88 | 3.57 | 0.81 | 0.011 | 6.74 |

| Diarrhoea | 522 | 2.86 | 2.62-3.11 | 2.76 | 2.96 | 0.93 | 0.406 | 2.99 | 2.67 | 1.12 | 0.206 | 3.14 |

| Haircoat disorder | 477 | 2.61 | 2.39-2.86 | 2.51 | 2.77 | 0.91 | 0.262 | 1.73 | 4.16 | 0.42 | < 0.001 | 9.24 |

| Thin / underweight | 397 | 2.18 | 1.97-2.40 | 2.29 | 2.07 | 1.11 | 0.315 | 0.92 | 4.27 | 0.22 | < 0.001 | 13.25 |

| Wound | 378 | 2.07 | 1.87-2.29 | 1.61 | 2.57 | 0.63 | < 0.001 | 2.20 | 1.86 | 1.18 | 0.119 | 5.55 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 350 | 1.92 | 1.72-2.13 | 2.40 | 1.46 | 1.64 | < 0.001 | 0.03 | 5.24 | 0.01 | < 0.001 | 15.37 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 333 | 1.82 | 1.64-2.03 | 2.00 | 1.65 | 1.21 | 0.082 | 0.24 | 4.59 | 0.05 | < 0.001 | 15.57 |

| Anorexia | 318 | 1.74 | 1.56-1.94 | 1.87 | 1.64 | 1.14 | 0.245 | 1.02 | 3.06 | 0.33 | < 0.001 | 10.72 |

| Conjunctivitis | 302 | 1.65 | 1.47-1.85 | 1.54 | 1.78 | 0.87 | 0.216 | 1.77 | 1.40 | 1.26 | 0.059 | 4.23 |

| Disorder not diagnosed | 286 | 1.57 | 1.39-1.76 | 1.40 | 1.72 | 0.81 | 0.081 | 0.75 | 2.87 | 0.26 | < 0.001 | 12.36 |

| Flea bite hypersensitivity | 266 | 1.46 | 1.29-1.64 | 1.71 | 1.19 | 1.44 | 0.003 | 1.17 | 1.95 | 0.60 | < 0.001 | 7.84 |

| Osteoarthritis | 252 | 1.38 | 1.22-1.56 | 1.48 | 1.3 | 1.14 | 0.301 | 0.07 | 3.67 | 0.02 | < 0.001 | 15.70 |

| Cat bite injury | 222 | 1.22 | 1.06-1.39 | 0.71 | 1.74 | 0.41 | < 0.001 | 1.36 | 1.02 | 1.33 | 0.047 | 5.64 |

| Cystitis | 202 | 1.11 | 0.96-1.27 | 1.15 | 1.06 | 1.08 | 0.578 | 0.93 | 1.46 | 0.64 | 0.001 | 7.71 |

| Lameness | 195 | 1.07 | 0.92-1.23 | 0.85 | 1.30 | 0.65 | 0.004 | 0.94 | 1.30 | 0.72 | 0.026 | 7.25 |

| Post-operative wound complication | 185 | 1.01 | 0.87-1.17 | 1.18 | 0.84 | 1.40 | 0.021 | 1.28 | 0.55 | 2.33 | < 0.001 | 1.67 |

| Cardiac dysrhythmia | 183 | 1.00 | 0.86-1.16 | 1.12 | 0.91 | 1.23 | 0.158 | 0.28 | 2.29 | 0.12 | < 0.001 | 13.69 |

| Otitis externa | 170 | 0.93 | 0.80-1.08 | 0.84 | 1.03 | 0.82 | 0.193 | 0.68 | 1.37 | 0.50 | < 0.001 | 8.83 |

| Over-grooming | 167 | 0.92 | 0.78-1.06 | 1.12 | 0.73 | 1.53 | 0.006 | 0.75 | 1.23 | 0.61 | 0.001 | 7.57 |

| Constipation | 153 | 0.84 | 0.71-0.98 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.645 | 0.50 | 1.46 | 0.34 | < 0.001 | 10.45 |

| Poor quality of life | 153 | 0.84 | 0.71-0.98 | 0.96 | 0.68 | 1.41 | 0.037 | 0.07 | 2.13 | 0.03 | < 0.001 | 16.78 |

| Road traffic accident | 148 | 0.81 | 0.69-0.95 | 0.67 | 0.95 | 0.71 | 0.033 | 0.99 | 0.43 | 2.30 | < 0.001 | 4.16 |

Sample: n=18249 cats under general practice veterinary care at VetCompass practices in 2019. P-values reflect females versus males, younger (<8 years) versus older (>8 years) cats. CI= confidence interval.

Discussion

This is the largest study to date using general practice veterinary data to report the prevalence of commonly diagnosed disorders in cats in the UK. The most frequently diagnosed disorders in cats in 2019 were periodontal disease (15.23%), obesity (11.58%), and dental disease (9.23%). Awareness by owners of the high frequency of dental and obesity issues in cats is important because these are conditions that are amenable to prevention and control, and therefore represent real welfare opportunities for pet cats.

Although gingivitis is considered a reversible condition with adequate plaque control and thorough dental home care, gingivitis progresses into periodontal disease as disease progresses, and periodontitis is essentially irreversible and progressive (Perry and Tutt, 2015). Similarly, the development and recognition of obesity should be readily apparent to owners, and represents another potentially preventable and reversible disorder (Wall et al, 2019).

A high prevalence of dental disease and obesity in cats not only suggests direct harm to health from these conditions, but may also predispose affected cats to multi-morbidities.

Periodontal/dental disease has been associated with direct oral pain and tooth loss, as well as systemic bacteraemia (Perry and Tutt, 2015) and chronic kidney disease (Greene et al, 2014). Obesity is a main risk factors for feline type 2 diabetes mellitus (Clark and Hoenig, 2021), mediated by insulin resistance (Rand et al, 2004) where insulin sensitivity is reduced by over 50% in obese cats compared with lean cats (Chastain and Panciera, 2002). Obesity has also been associated with increased risk of dermatological issues, osteoarthritis, cardiovascular disease, neoplasia, and urolithiasis (Laflamme, 2012). However, with good owner motivation and veterinary intervention, suffering caused by painful, debilitating and eventually life-limiting conditions that are highly preventable could be avoided in pet cats (Wall et al, 2019).

The present study also identified that female cats had increased prevalence of poor quality of life, post-operative complications (including post-spay issues) and hyperthyroidism, amongst other disorders, while males were more likely to have periodontal disease, road traffic accidents, heart murmur, lameness, obesity, and cat bite abscesses, amongst others. Younger cats (<8 years) had increased prevalence of cat bite abscesses, flea infestation, and road traffic accidents, while older cats (≥ 8 years) were more likely to have more than one disorder overall, including lameness, cystitis and dental disease, among others. These results support earlier evidence that cats tend to develop multi-morbidities as they advance in years (Lund et al, 1999) and can assist tailoring of preventative health care advice to the specific age and sex of individual cats for greater effect. For example, owners of young male cats could be advised to keep these cats indoors or to introduce night curfews to prevent or reduce the risk of road traffic accidents risk and cat fighting. Greater emphasis could be placed on ensuring older cats are assessed for multi-morbidities, with females in particular being assessed for hyperthyroidism when weight loss is noted.

Building on this awareness of common conditions overall and on the relative risks linked to sex and aging, veterinary teams can play a key supporting role in ensuring good health is maintained in pet cats. Effective communication with owners is critical, for example adding attention-grabbing information about dental disease and obesity into kitten packs and sharing reliable information on the high frequency and welfare impacts from these diseases, along with useful information on preventive actions that owners can take. Veterinary practices can also use an infographic that has been produced on the study to share information with owners on the most common disorders in cats, free to download and share from https://www.rvc.ac.uk/Media/Default/VetCompass/Info-grams/220222%20Common%20cat%20disorders.pdf (Figure 1). Veterinary nurse clinics could be used more effectively at early intervention points to promote better oral health care and give advice about weight gain in pet cats (Woolf, 2014). Overall, these results across the spectrum of common disorders in cats can assist veterinarians, veterinary nurses, cat breeders and cat owners by providing an evidence base to understand and predict disorder occurrence, and to identify key health and welfare opportunities for their cats. Veterinary professionals can now help their clients by sharing these insights.

KEY POINTS

- Better understanding of age-related disorder risk can allow for more targeted prevention, diagnosis and clinical management

- Effective communication with owners is critical

- These results across the spectrum of common disorders in cats can assist veterinarians, veterinary nurses, cat breeders and cat owners by providing an evidence base to understand and predict disorder occurrence, and to identify key health and welfare opportunities for their cats.