Small intestinal surgery is commonly performed in first opinion practice. It may be indicated for biopsy, removal of foreign body obstruction or resection of neoplasia, non-viable tissue or irreparable injury. The consequences of postoperative intestinal leakage are significant morbidity and mortality, necessitating revision surgery or euthanasia. Enterotomy (a simple incision into the intestinal lumen) and enterectomy (removal of a length of intestine) followed by anastomosis (re-apposition of the cut gut ends) are the most frequently performed procedures, with enterectomy anastomosis having a reported dehiscence rate between 7 and 16% (and higher if there is pre-existing septic peritonitis).

There are multiple factors that may increase the risk of postoperative leakage and subsequent septic peritonitis. It can be helpful to classify risk into three major groups to identify them logically, help recognise animals at greatest risk of dehiscence and, if possible, address the potential causes (Table 1). This article focuses on practical procedural considerations that are applicable to general practice, and highlights methods of optimising the biological and mechanical environment of the intestinal surgical site for healing.

Table 1. Factors that may increase the risk of postoperative intestinal dehiscence

| General risk factors |

|---|

| Hypoalbuminaemia (≤2.5 g/dl) |

| Azotaemia |

| Neutrophilia |

| Intestinal foreign bodies and particularly linear foreign bodies |

| Requiremed use of blood products |

| Delayed enteral feeding |

| Local biological factors |

| Pre-existing septic peritonitis–increased collagenase activity weakens the intestinal incision |

| Contusion |

| Ischaemia |

| Local mechanical factors |

| Tension |

| Failure of sutures or staples |

| Incomplete closure or poor suture technique |

Core surgical principles to minimise negative effects on healing

Application of Halsted's surgical principles can minimise the negative impact on the tissues for all surgeries and the small intestine is no exception. These are:

- Asepsis

- Gentle tissue handling

- Precise haemostasis

- Preservation of blood supply

- Closure of dead space

- Closure without tension

- Accurate apposition of tissues.

Minimising contamination of the abdominal cavity when the intestine is opened can be done by packing off the area using moistened sterile gauze, milking contents of the intestine away from the surgical site and then occluding the lumen of the gut. Intestinal surgery is classified as clean-contaminated because of the intraoperative exposure of contaminated intestinal lumen during surgery. Surgical instruments and gloves should be changed after completing the enterotomy or enterectomy, to help maintain asepsis.

Gentle tissue handling is performed by using stay sutures when possible, atraumatic thumb forceps (DeBakey rather than toothed for anything other than skin and tough fascia) and atraumatic Doyen bowel clamps to occlude the lumen. It is important to apply the central part of the Doyen clamp across the intestine and only close the clamp gently, at the first click of the ratchet. This is often all that is required to occlude the lumen and avoid trauma to the gut. Visualise the tips of the instrument to avoid crushing mesenteric vessels or other viscera. Digital occlusion of the intestine by an assistant is a less traumatic method to obstruct the lumen.

All regions of the small intestine (duodenum, jejunum and ileum) have four layers. Listed from outside to inside they are the thin superficial serosa (a reflection of visceral peritoneum), the muscularis propria, the tough fibrous submucosa and the glandular mucosa. Accurate alignment of tissue layers when suturing can promote complete mucosal healing as early as 4 days after surgery, and minimise the magnitude of inflammation and fibrosis. Inversion and eversion of the intestinal wall can delay the healing process, reduce luminal diameter or result in problematic adhesion formation (Abramowitz and Butcher, 1971; Jansen et al, 1981; Ellison et al, 1982). Only the submucosa provides a secure anchor for sutures and it must be engaged with each passage of the needle (Halstead, 1887).

Healing and the timing of dehiscence

Initially, the surgical repair and the formation of a serofibrinous seal prevents leakage. Neutrophils are the predominant leukocyte present at the site for the first few days. They are responsible for clearing bacteria and debriding non-viable tissue, but also for weakening the fibrin coagulum. Macrophages then migrate to the area, stimulating fibroblast deposition of collagen, ultimately strengthening the repair. The security provided by collagen lags the removal of fibrin support by approximately 3–5 days (in a healthy animal), explaining why intestinal dehiscence often occurs several days after an apparently successful surgery. Intestinal leakage and septic peritonitis (if not present preoperatively) within the first 3 days or so after surgery are often more attributable to surgical error, whereas those occurring more than 3 days postoperatively may be more likely to have a physiological cause.

Suture material, diameter and needle shape

Choice of suture material for intestinal closure can vary between surgeons, in particular whether synthetic absorbable monofilament or multifilament suture is used. However, multifilament material can cause more trauma (friction from increased drag as suture is pulled through tissue), inflammation, allow fluid (and therefore possibly bacteria) to ‘wick’ along the material by capillary action and will more readily harbour and grow bacteria (Kirpensteijn et al, 2001; McCagherty et al, 2020). Use of synthetic absorbable monofilament sutures as poliglecaprone 25 (Monocryl; Ethicon), polyglytone 6211 (Caprosyn; Covidien), polydioxanone (PDS II; Ethicon), glycomer 631(Biosyn; Covidien) and polyglyconate (Maxon; Ethicon) avoids these issues and retains appropriate strength for a suitable period of time. As a result, Monocryl and PDS are the most commonly used materials to suture the intestinal tract in the UK (House, 2015).

Healthy intestine heals to between 80 and 100% of its normal strength in approximately 14 days. The ideal suture material predictably loses tensile strength at the same rate that the surrounding tissue regains it and is residual in the tissue for the least time possible, minimising the risk of foreign body reaction. Monocryl has advantages over PDS for small intestinal closure, since it has a higher initial tensile strength, is absorbed more quickly and loses tensile strength at a more appropriate rate (House, 2015). Despite this, in the authors' experience, most veterinary surgeons use PDS for intestinal closure (including the authors), particularly if there is concern regarding risk factors for delayed healing.

Knot security is inversely proportional to material diameter. For small dogs and cats, 1.5M (4–0) and for larger dogs 2M (3–0) diameter material is suitable for the small intestine and optimises tensile strength vs knot security. Swaged on needles are standard of care for intestinal surgery. Round bodied or taper cut needles are preferred to reverse cutting needles. This is because their needle profile more accurately approximates the cross sectional shape and area of the material, and they are designed to separate tissues, rather than cut a defect through the tissue, theoretically resulting in a tighter seal when the tissue relaxes back onto the material. It can also be easier to feel resistance as the submucosa is engaged, to ensure appropriate bites are taken of the tension-holding anatomical layer.

Suture pattern

Simple continuous or simple interrupted patterns can be used to close an enterotomy. Knotting a material weakens it by approximately 50% because the material is damaged by the process of being deformed. If one were to compare the risk of at least one knot snapping along a row of simple interrupted sutures (for example seven knots) versus one of the knots in a simple continuous suture (two knots), then there is a higher risk of at least one failure for the interrupted row. When considering the intestine specifically, the failure of a single knot can result in septic peritonitis, whether from a small focal leak or the entire closure being compromised, so it would seem sensible to use fewer knots, which can be achieved with a simple continuous pattern. Additionally, each simple interrupted knot has a different inherent tension (force crushing the tissue) along the row, compared with a continuous pattern where the tension is distributed more evenly between bites. Finally, continuous sutures provide a watertight closure and more accurate tissue apposition compared to simple interrupted rows. When placing a continuous suture, the authors prefer to take a full thickness bite of the intestine a couple of millimetres before and after the start and end of the enterotomy closure respectively, to ensure that healthy, viable submucosa has been engaged in these crucially important bites.

An inverting pattern is superior to an everting pattern, which has been associated delayed restoration of mucosal continuity, higher complication rates, increased adhesions, septic peritonitis and death. However, a simple approximating pattern results in a faster healing process and mucosal regeneration, with no compromise in luminal diameter, when performing resection anastomosis compared to an inverting pattern (Loeb, 1967; Abramowitz and Butcher, 1971; Ellison et al, 1982).

A simple continuous suture pattern is also recommended for closure of simple enterectomy and anastomosis for all these reasons. This pattern uses less material and is quicker, minimising anaesthesia time and risk of morbidity in the animal. Using two separate pieces of suture avoids excessive tension and stenosis of the lumen, with one suture beginning on the mesenteric border and the other on the antimesenteric border (Box 1). Placing these knots first means that the intestine will be closed without twisting and can help with accommodating luminal diameter disparity, with more widely separated bites on one side and smaller on the other. The first suture can then be tied off to the ear of the second suture anchor, creating a 360° continuous suture without a purse string effect. The ears of the knots can also be used to manipulate the intestine and minimise traumatic injury from the use of thumb forceps. Simple interrupted closure tends to leak at the mesenteric border, because it is more challenging to identify an appropriate bite of the intestinal wall with the mesenteric fat present.

Box 1.Simple continuous closure of the small intestinal enterectomy/anastomosis

-

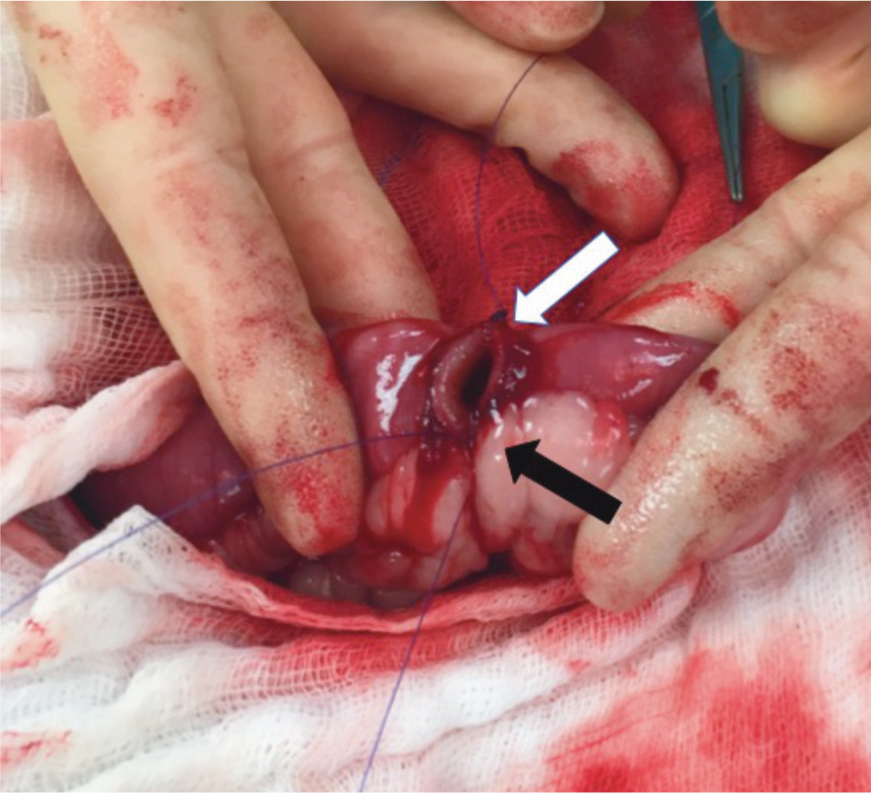

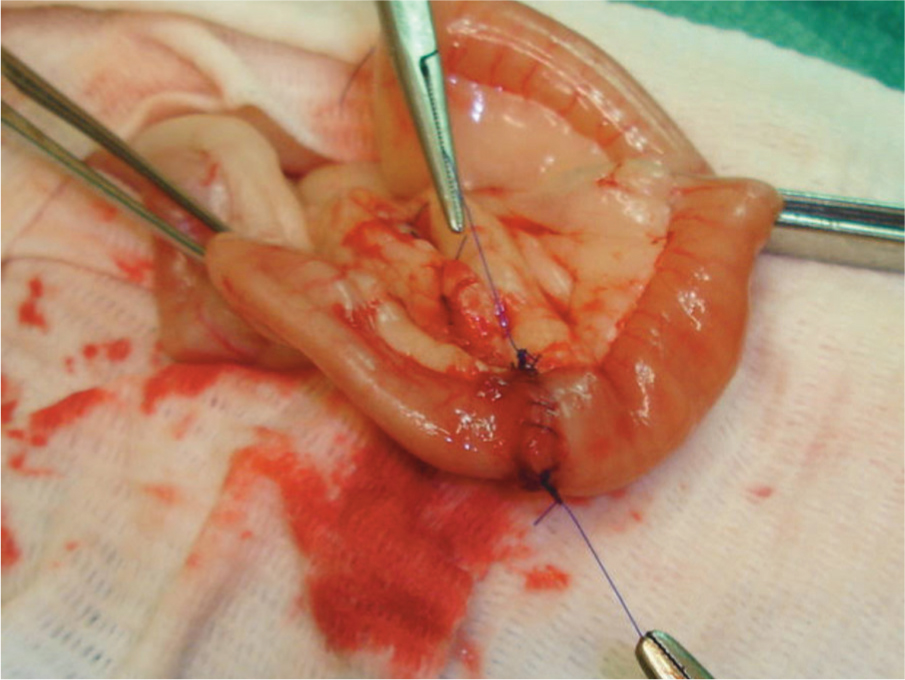

Suture 1 is tied at the mesenteric border by passing the needle full thickness from extraluminal to intraluminal in the first bite, then intraluminal to extraluminal in the other open end of the intestine and an extraluminal knot is tied (at least two square knots) leaving a long ear (this is the first knot at the 6 o'clock position, black arrow). A second piece of material is used to repeat these steps at the antimesenteric position (12 o'clock position) and create a second knot (white arrow).

-

Suture 1 is used to create a simple continuous suture up the near side of the anastomosis, tying off to the long ear of the second knot.

-

The second suture created a simple continuous run down the opposite side of the anastomosis, tying off against the long ear of the first knot.

The authors recommend full thickness bites of the intestinal wall to ensure that the submucosa has been included. This does not result in higher complications compared with partial thickness bites (for example, modified Gambee pattern), it is quicker and is more reliably performed (irrespective of surgeon experience).

Stapled enterectomy and anastomosis

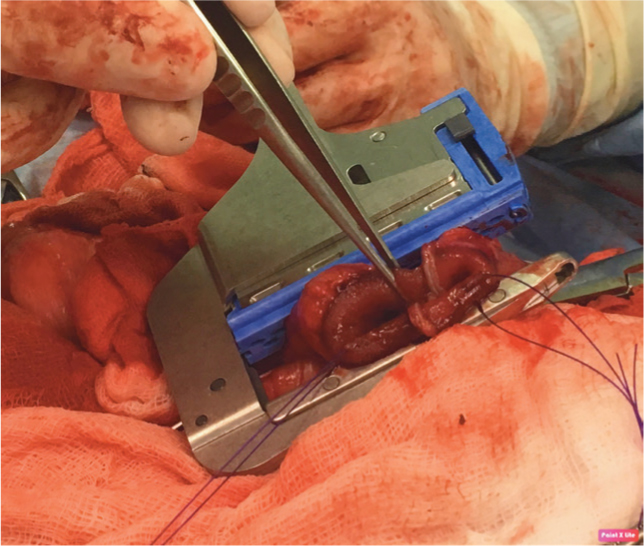

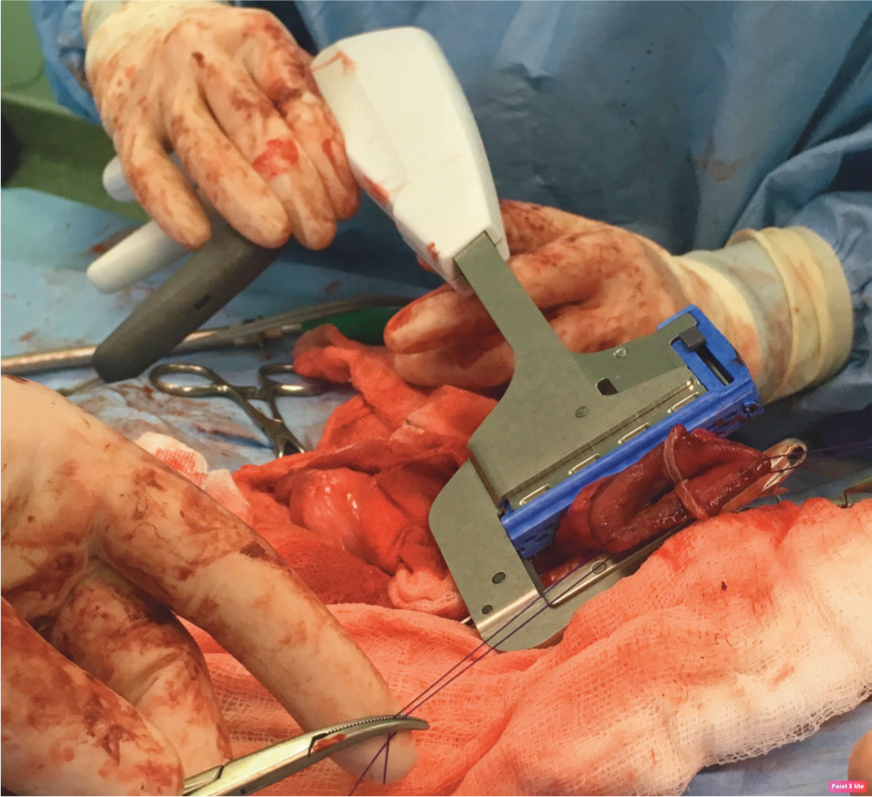

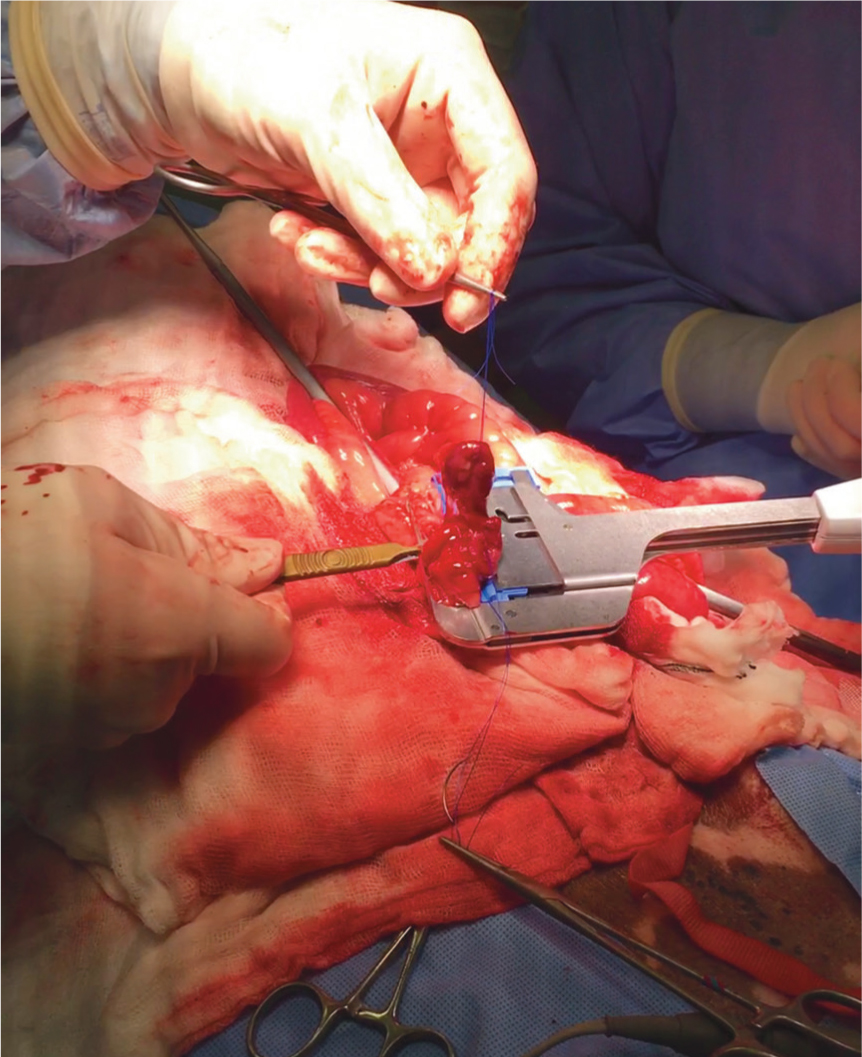

Surgical skin staplers can be safely used for intestinal surgery, but the authors have no personal experience of this. However, the authors would strongly advocate for the creation of functional end-to-end anastomoses using a combination of linear stapling and linear-cutter stapling devices (Box 2), with the addition of a suture in the crotch of the anastomosis.

Box 2.Functional end to end anastomosis using a linear stapling device and linear-cutter stapling device

-

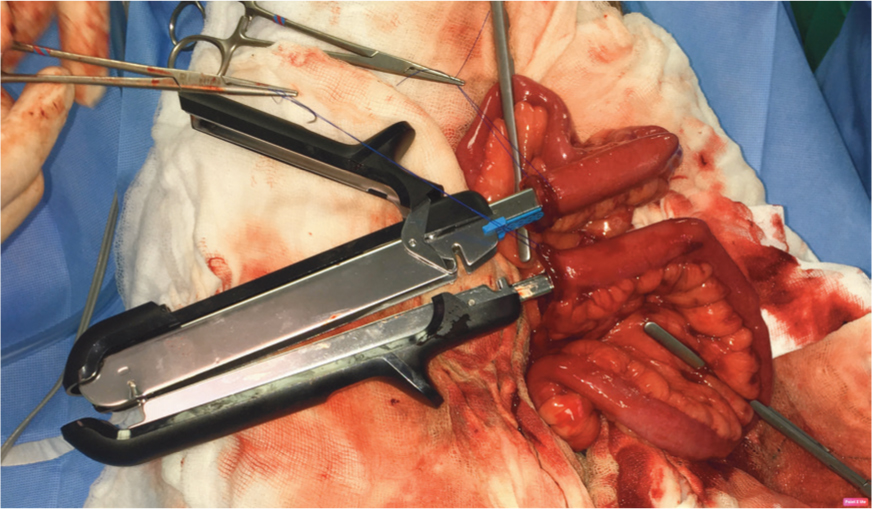

An enterectomy has been performed and Doyen bowel clamps used to occlude the lumen. Stay sutures are used to manipulate the cut ends of intestine and pull them onto the jaws of the dismantled linear cutting stapler device.

-

The linear cutting stapler is closed (halves are pieced together; side handle closed), apposing the intestine ends side-to-side. The sliding toggle on the side of the device is pushed forwards and then pulled back, firing two parallel rows of staples with a sharp cut between them. The intestine now has an appearance of a pair of trousers with an open waist.

-

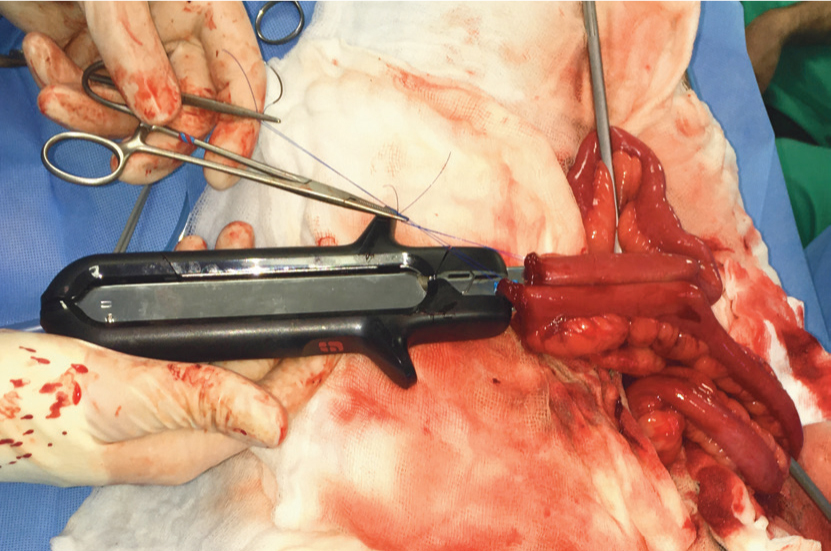

The belt is placed on the waist of the trousers using a linear stapling device. Offset the previous staple lines rather than apposing them, to avoid too many overlapping staples.

-

Finally, cut the redundant tissue away from beyond the linear stapler and place one or two simple interrupted sutures between the two pieces of intestine in the crotch of the trousers to support a potential weak point in the functional end-to-end anastomosis (literally side-to-side, with a communicating lumen).

-

A linear gastrointestinal anastomosis (GIA) stapler (used for laparoscopic surgery in humans) can be used for small sized animals when the intestinal lumen is too narrow for a standard linear cutting stapler.

One study found that sutured anastomoses resulted in dehiscence in 8.1% of cases, compared with 4.2% of cases that were stapled (not statistically significant based on patient numbers). However, cases of dehiscence in dogs with septic peritonitis was 28.9% with sutures, versus 9.7% for stapled anastomoses, which was statistically significant (Davis et al, 2018). In vitro evidence suggests leakage resistance can be further increased by oversewing the transverse staple line (Chu et al, 2020).

The procedure is quick, taking around 5–10 minutes. The tension is homogeneously distributed along the anastomosis, gastrointestinal function and luminal diameter are maintained and the B-shape of the closed staples preserves the capillary blood supply to the tissues. It also creates a functional end-to-end anastomosis when managing significant disparity in luminal diameter. Surgeons may be discouraged to perform this technique if they are unfamiliar with the equipment or by the cost of the devices required. However, the reduction of time spent in surgery and under anaesthesia can mitigate costs and minimise animal morbidity, particularly in critically ill animals and for out-of-hours procedures (Ullman et al, 1991; White, 2008). Unlike the rarely used specific end-to-end stapling devices, simple linear staplers and linear cutter staplers can be adapted for other surgical uses if kept in stock, such as lobectomy of the liver or lung.

Leak testing

Leak testing involves actively distending an occluded segment of intestine with sterile saline through a 25G needle intraoperatively and visually assessing for fluid egress at the surgical site. This is most valuable if performed correctly, as underfilling or overfilling of the gut will impair accurate identification and assessment of a leak. Intraluminal pressures in the intestine vary from 2–4 mmHg to 15–20 mmHg. Digital or Doyen occlusion of 10 cm of jejunum should be performed and the lumen should then be injected with 16.3–19 ml and 12.1–14.8 ml of saline, respectively (Saile et al, 2010). If there are any locations where there is concern regarding closure or if a leak is identified, then additional full thickness simple interrupted sutures are specifically placed.

Omentalisation and serosal patching

Omentum can be wrapped around the intestine following closure, to provide support and additional blood supply. It is worth noting that many of the reported benefits of this procedure are taken from human research and the omentum of humans is quite different to that of small animals. While the benefit to enterotomy or enterectomy security is questionable, it doesn't do any apparent harm and in the authors' experience, this procedure can be beneficial in minimising adhesion formation to more vital anatomy or the midline abdominal incision (McLackin and Denton, 1973).

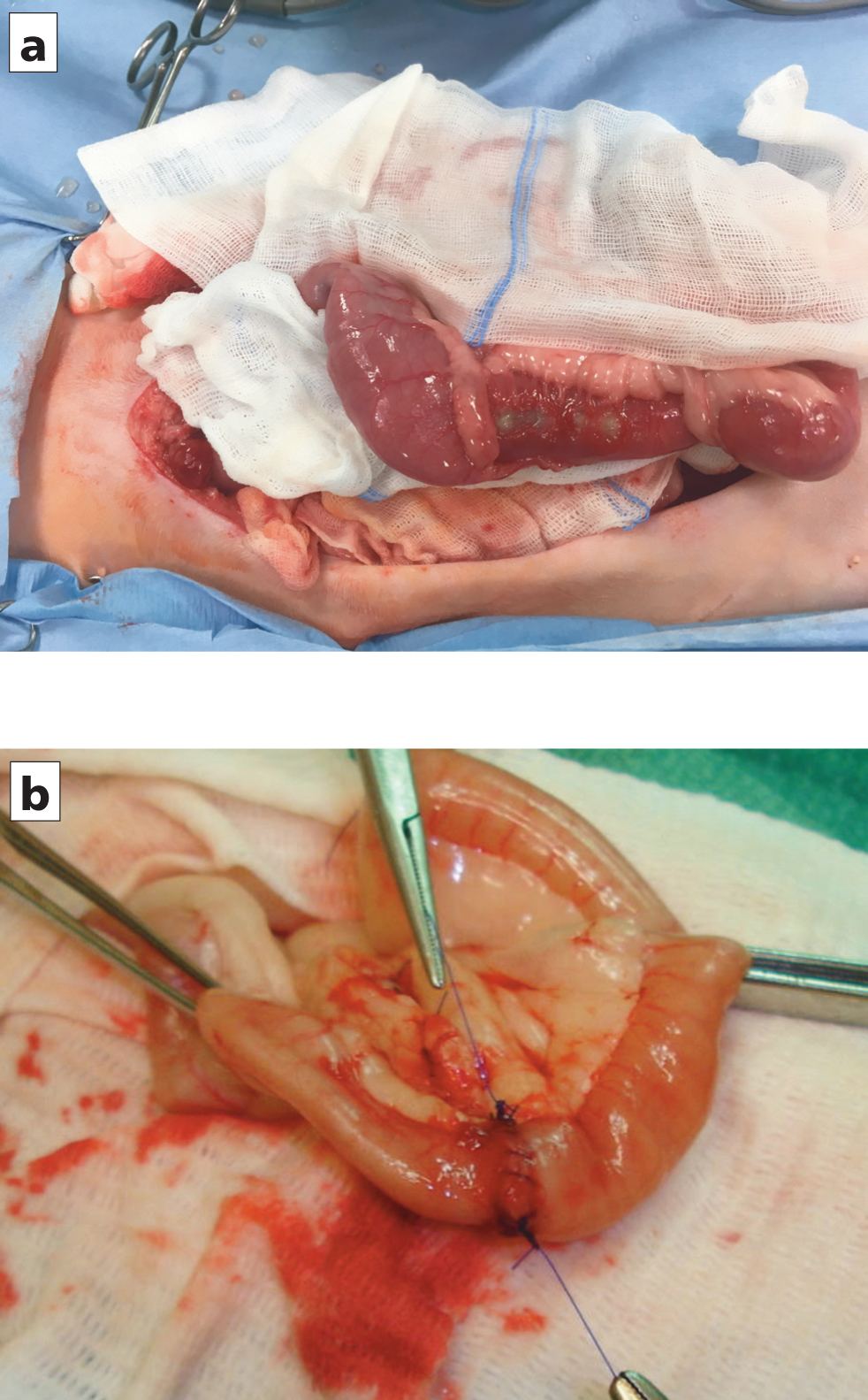

Serosal patching may provide more mechanical support immediately postoperation, as shown in a cadaveric study by Hansen and Monnet (2013). The authors prefer to perform this procedure over omentalisation, if there is a genuine concern regarding impaired intestinal healing (Figure 1).

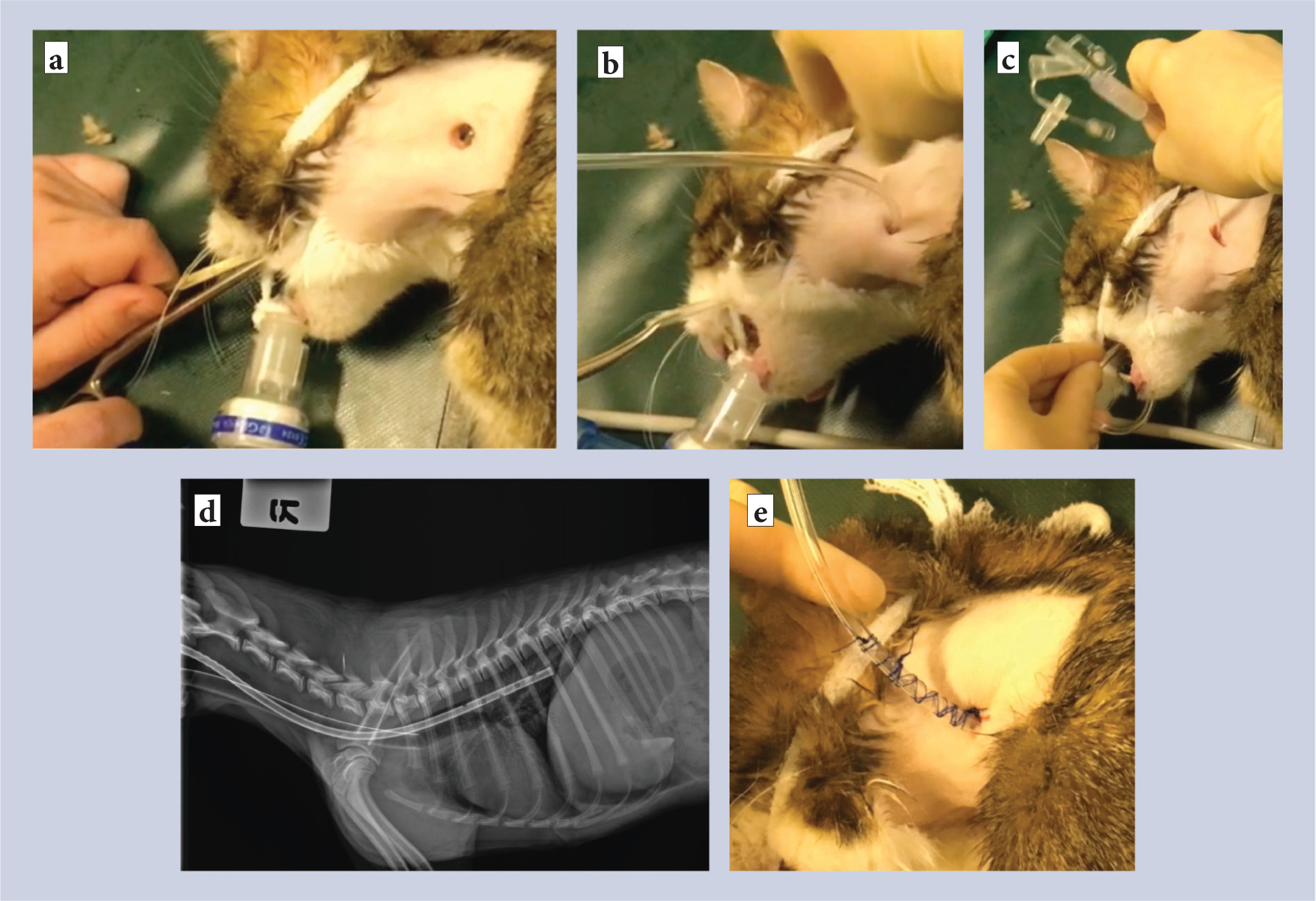

Feeding tubes

Early enteral feeding promotes regeneration of the intestinal wall by nourishing enterocytes and encouraging normal gut motility (Braga, 2001; Kouti et al, 2006). Oesophagostomies, referred to as O-tubes (Figure 2), or surgically placed gastrotomy tubes (G-tubes) are easily placed during an abdominal procedure. If an animal is inappetant postoperatively, then a nasogastric tube can be placed while the animal is conscious, but this is not as well tolerated. O-tubes are generally very well tolerated, have a low complication rate and can be removed immediately if an animal eats. G-tubes can be used to periodically decompress and empty the stomach (in ileus), as well as provide nutrition. However, G-tubes are technically a little more complex to place, have a marginally higher complication rate (septic peritonitis can still be a major problem) and they must remain in place for approximately 14 days before they can be removed, irrespective of the animal's appetite, which generally requires owner education and compliance. A feeding tube should be considered as the standard of care for a patient with marked peritonitis or septic peritonitis, when one would expect an animal not to eat postoperatively. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

KEY POINTS

- Single layer, full thickness, simple continuous closure of the intestine following both enterotomy and enterectomy using a monofilament absorbable material is safe and recommended.

- Stapled functional end-to-end anastomoses are simply performed and have a lower postoperative dehiscence risk compared with sutured anastomosis, particularly in animals with septic peritonitis.

- Leak testing can detect a potential problem but needs to be performed correctly to be useful.

- Omentalisation and serosal patching can be used to support intestinal repair.

- Early enteral feeding is extremely important for gut healing; placing an oesophagostomy or gastrostomy feeding tube in animals where postoperative anorexia is expected is beneficial with a low risk of complications.