Fluid therapy is an essential part of the emergency treatment of critical avian patients. In small or collapsed, very unwell or severely dehydrated patients, gaining intravenous (IV) access may be extremely difficult. Fortunately, fluid therapy and many IV medications can be given via an intraosseous (IO) catheter placed directly into an appropriate bone that allows for their quick absorption into the vasculature (Bowles et al, 2007). Note that hypertonic or strongly alkaline drugs should not be given by this route (Quesenberry and Hillyer, 1994).

In birds the distal ulna bone is often chosen for securing IO access, since it is not a pneumatised bone connected to the respiratory tract. In the author's opinion this site is relatively easily accessible and well-tolerated in raptors and companion avian species. This article provides a guide to IO catheter placement in the avian distal ulna.

Considerations for use

Compared to an IV catheter, an IO catheter has the advantage of being more difficult for the patient to disrupt or remove. Additionally, patient interference will not result in blood loss (which could lead to exsanguination), which can be a concern with IV access. Intraosseous catheters can be left in situ for up to 72 hours; they require regular monitoring and maintenance during this time, including flushing every 6 hours while in place (Edis, 2016).

Placing an IO catheter can be more challenging than placing an IV catheter. Practicing the technique on cadavers will allow the clinician to feel confident in placing an IO catheter in an emergency situation when IV access is unattainable. Competent technique will also reduce the likelihood of potential complications such as fluid extravasation, iatrogenic fractures and osteomyelitis. Intraosseous catheters should not be placed in septic patients or those with metabolic bone disease (Edis, 2016).

If there is any concern that the bone may be fractured or otherwise damaged then this should be investigated before placement or a different site used: these sites may include the opposite ulna (distal or proximal approach) or the tibiotarsus in the leg.

A further potential barrier to placement of an IO catheter in reproductively active female birds is hyperostosis of the long bones. Oestrogen stimulation may result in thickened bone cortices and mineral deposition in the marrow cavity (Lennox, 2008).

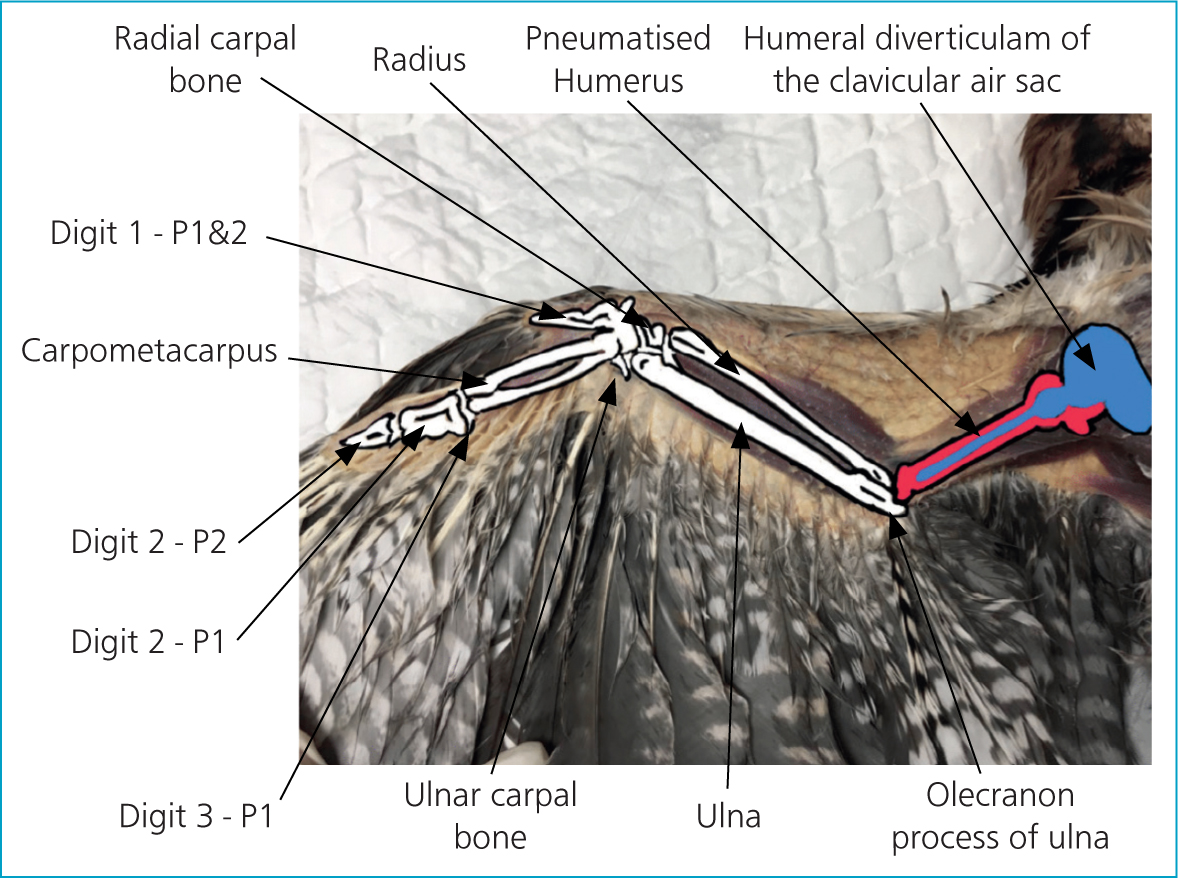

Relevant wing anatomy

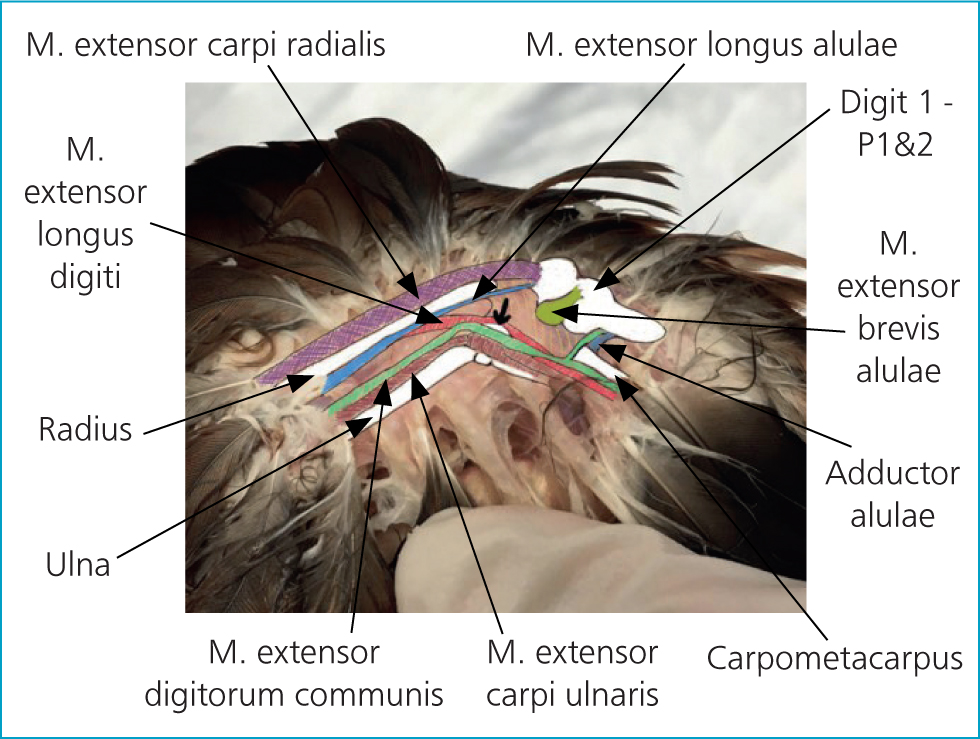

With few exceptions, birds have a hollow, pneumatised, humerus that contains an opening in the proximal wall called a pneumatic foramina. This opening allows for the humeral diverticulum of the clavicular air sac to enter the internal cavity of the humerus (Cubo and Casinos, 2000). Fluid inserted into a pneumatised bone may result in the patient drowning, therefore these bones should not be used. In contrast to mammals, the radius in birds is smaller than is the ulna, which makes the ulna a more appropriate site for IO catheter placement (Dubé et al, 2011) (Figure 1).

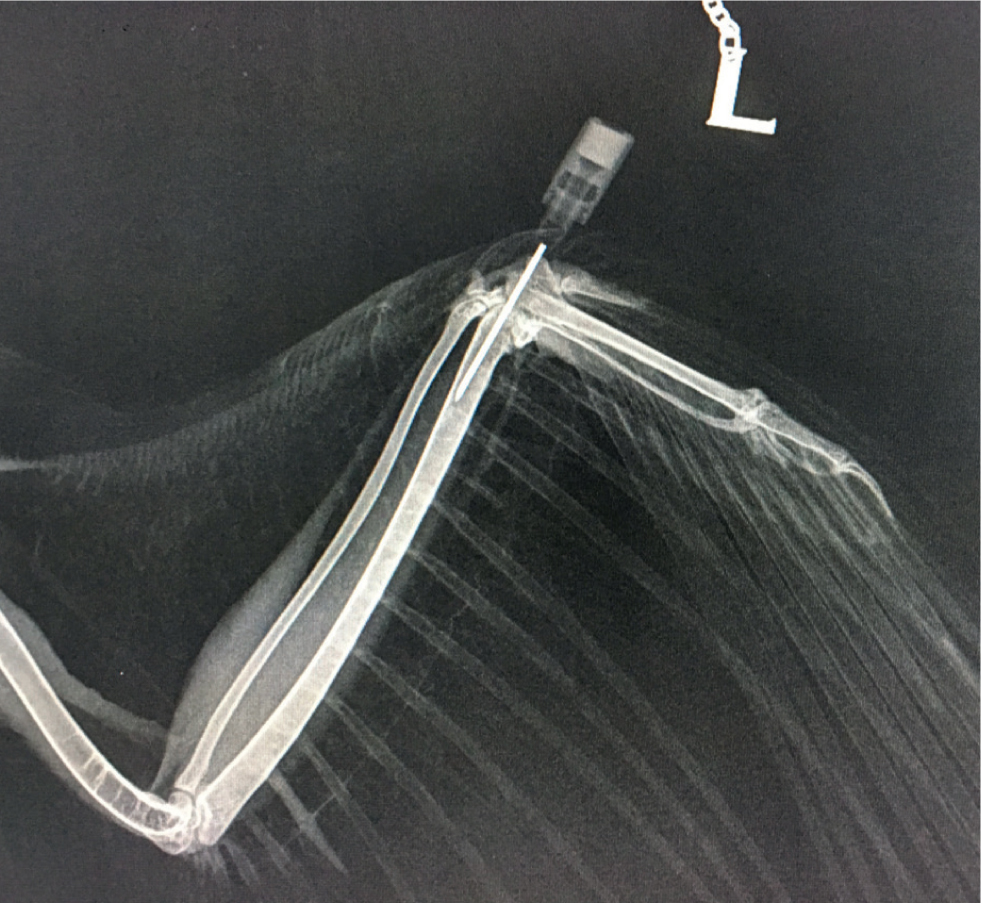

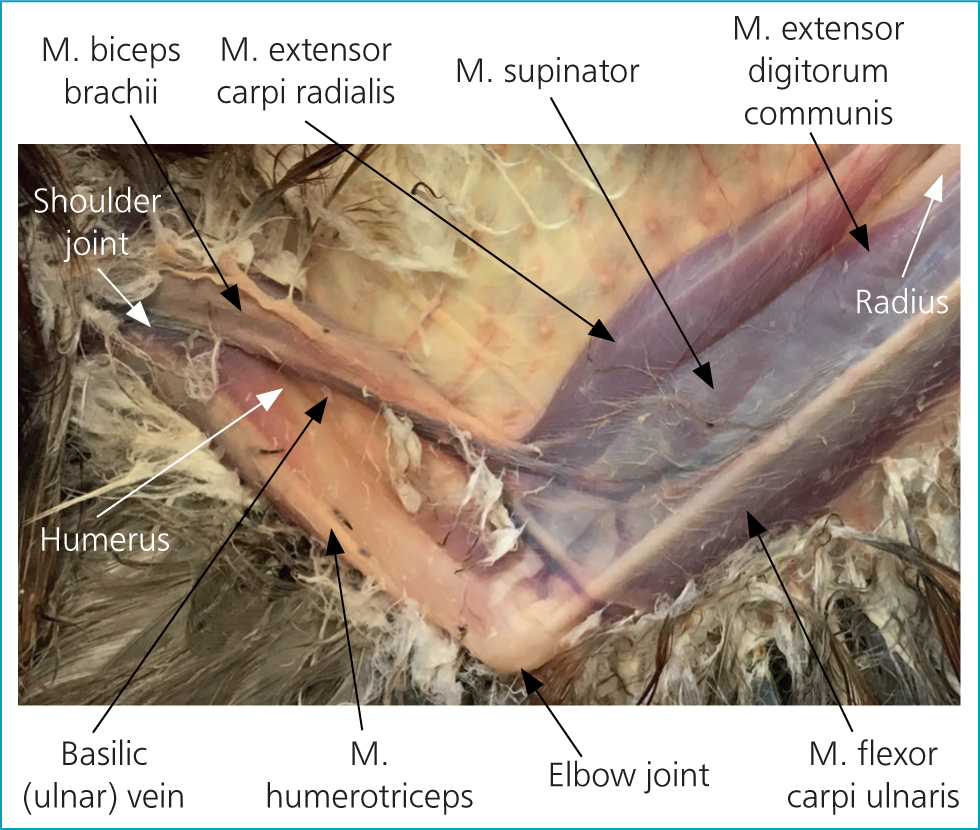

Using an incorrectly-positioned IO catheter can be extremely painful for the patient, therefore the position of the IO catheter should be confirmed. To assess placement the ulna should be palpated to ensure that the point of the needle has not exited the bone proximally, and radiography should be performed (Figure 2). In addition, flushing the catheter can be performed to ensure correct placement: the bolus given IO can be seen as it passes along the basilic vein (Figure 3) (Chitty, 2005).

Equipment

Placement of an IO catheter should ideally be undertaken under general anaesthesia. A small animal anaesthetic circuit with an Ayres' T-piece with a Jackson Rees' modification and an appropriately sized anaesthetic mask or endotracheal tubes will be required.

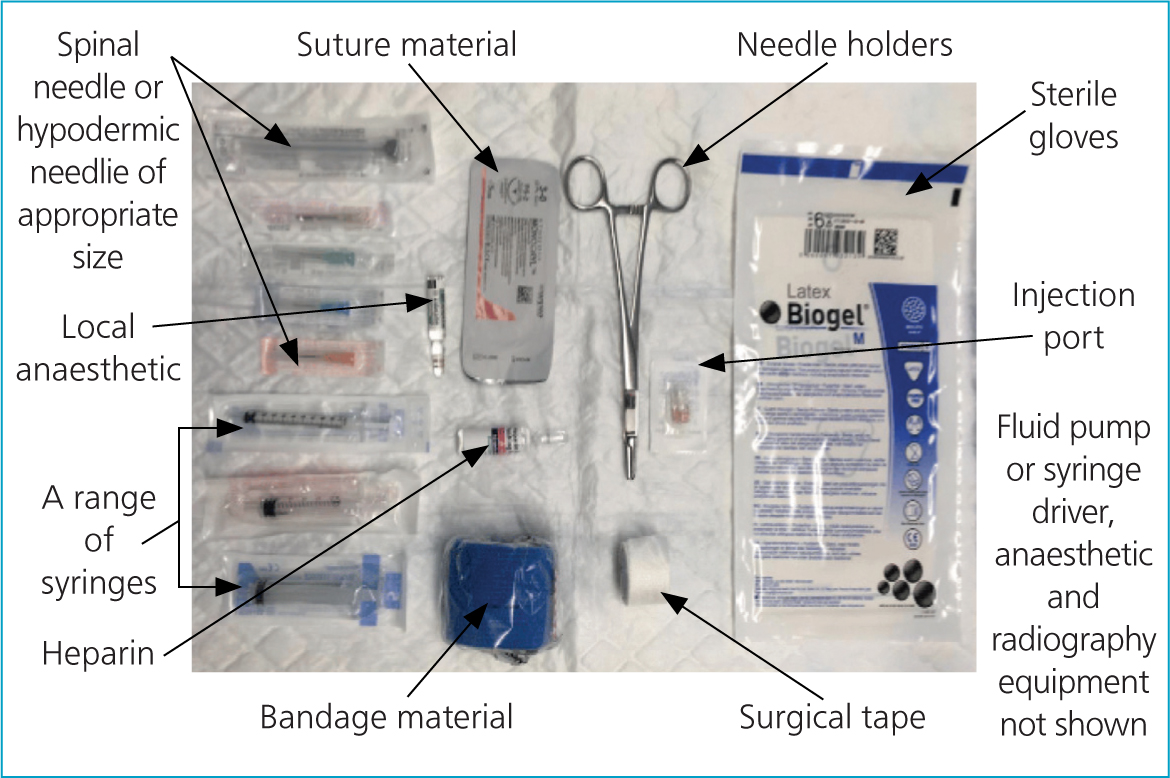

Either a spinal needle or a hypodermic needle of an appropriate size can be used as an IO catheter. A spinal needle has the advantage of having a stylet, which may help to prevent the lumen from becoming blocked with cortical bone; however, they are often not readily available. In psittacines, a 20–25-gauge spinal needle or hypodermic needle is suggested; selection should be based on the individual patient (Powers, 2006). As a guide the author suggests that a 23–25-gauge 1-inch needle may be suitable for a 100 g cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus); a 21-gauge 1 inch needle for a 500 g African grey parrot (Psittacus erithacus); an 18–20-gauge 1.5 inch needle for an approximately 1 kg blue-and-yellow Macaw (Ara ararauna) or Harris Hawk (Parabuteo unicinctus); a 14-gauge may be suitable for a chicken (Gallus gallus) or turkey (Meleagris gallopavo).

A 1 ml syringe (Figure 4) can be used similarly to an orthopaedic chuck, to help hold the needle and drive it into position.

An appropriate local anaesthetic such as 2% lidocaine (without adrenaline) is recommended to anesthetise the insertion site before placement. An injection port, heparinised saline, surgical tape, needle holders and bandaging material are required to secure and flush the IO catheter. Polyglecaprone 25 (Monocryl, Ethicon) in sizes 3–0 to 6–0 is one appropriate choice of suture material (Guzman, 2016). Sterile gloves should be worn throughout the procedure.

Fluid will not run into the IO catheter without the use of a fluid pump or a syringe driver; if these are not available then alternatively slow boluses of fluid can be given manually via the catheter.

The procedure

Pre-placement anaesthesia and systemic analgesia

Intraosseous catheter placement is likely to be both stressful and uncomfortable for the patient, therefore general anaesthesia and appropriate pre-emptive analgesia should be used whenever possible. In patients in acute crisis this may, however, not be possible and appropriate analgesia should be given at the earliest opportunity once the patient is stabilised. Once in the correct position, an IO catheter should be no more uncomfortable for the patient than an IV catheter.

Anaesthesia can be induced using isoflurane or sevoflurane using 100% oxygen as the carrier gas, delivered via an appropriately sized mask and an Ayres' T-piece anaesthetic circuit with a Jackson Rees' modification.

Where possible patients should be intubated with a small non-cuffed endotracheal tube or an appropriately sized IV catheter. Small birds may have a larger epiglottis than expected; this can be easily visualised at the base of the tongue to allow for the selection of an appropriate tube size.

In choosing analgesia similar criteria should be applied as per mammals and similar drug contraindications presumed. A multi-model approach to pain relief before IO catheter placement is ideal. Meloxicam (0.5–2 mg/kg) is a non-steroidal anti inflammatory drug commonly used in avian species and aims to provide pain relief through the reduction of inflammation (Balko and Chinnadurai, 2017). This can be combined with butorphanol (1–3 mg/kg) as the opioid of choice for birds (Lierz and Korbel, 2012); however, there is some evidence that indicates that buprenorphine (0.1–0.6 mg/kg) may be a better choice in some raptors (Ceulemans et al, 2014).

Aseptic preparation of catheter site

Before performing the procedure, the insertion site should be aseptically prepared. Approach the wing dorsally, flex the carpus and palpate the carpal joint. A few feathers over the distal ulna can be plucked and the area cleaned and aseptically prepared with dilute povidone-iodine using a similar technique to that used in small companion mammals.

Local analgesia

The periosteum and the structures overlying the site of the needle insertion should be locally anaesthetised before placement of the IO catheter. Local analgesia is valuable part of a multimodal analgesia protocol. However, care should be taken to ensure that accurate dosages of local anaesthetics are calculated and adhered to, since overdose can prove fatal in birds (Balko and Chinnadurai, 2017). Dilution of lidocaine 1:10 for use in avian patients can aid accurate calculations (Bowles et al, 2007). Lidocaine preparations without adrenaline have been safely used at doses up to 6.0 mg/kg (Brando et al, 2015) and appear to provide good local analgesia.

It is important to make sure that you can identify the insertion site for your IO catheter before administering local anaesthetic; once you have applied local analgesia it may be more difficult to palpate. The proximal tip of the ulna is located under the ligaments of the extensor carpi ulnaris and extensor digitorum communis (Figure 5). The insertion site can be identified on the ulna as a bony plateau-like depression just distal to the condyle (identified with an arrow in Figure 6 and in P2 in Figure 5) and local anaesthetic can be injected over it.

Insert the intraosseous catheter

To insert the IO catheter (Figure 6):

- Hold the limb flexed in the non-dominant hand and place one finger on the ventral aspect of the long axis of the ulna. A 1-ml syringe attached to the hypodermic needle may improve control and make placement easier

- Identify the needle insertion site in the midportion of the condyle and insert the needle, allowing for the curve of the ulna. The curve of the ulna varies between species (Figure 7) and can be more easily palpated ventrally. Insert the tip of the needle into the periosteum and gently advance through the bone cortex: a ‘pop’ and a reduction in resistance can be felt as it passes into the medullary cavity

- Flush the catheter with a small amount of heparinised saline. Resistance suggests that the needle may be blocked by bony matter. Remove the blocked needle and insert a new needle into the guide hole produced by the first needle

- Flushing the needle with sterile saline before insertion may decrease the likelihood of this occurring

- Close the IO catheter with an injection port

- Assess placement by: palpation of the ulna to ensure that the point of the needle has not exited the bone; flushing the catheter and observing the bolus passing through the basilic vein; radiography.

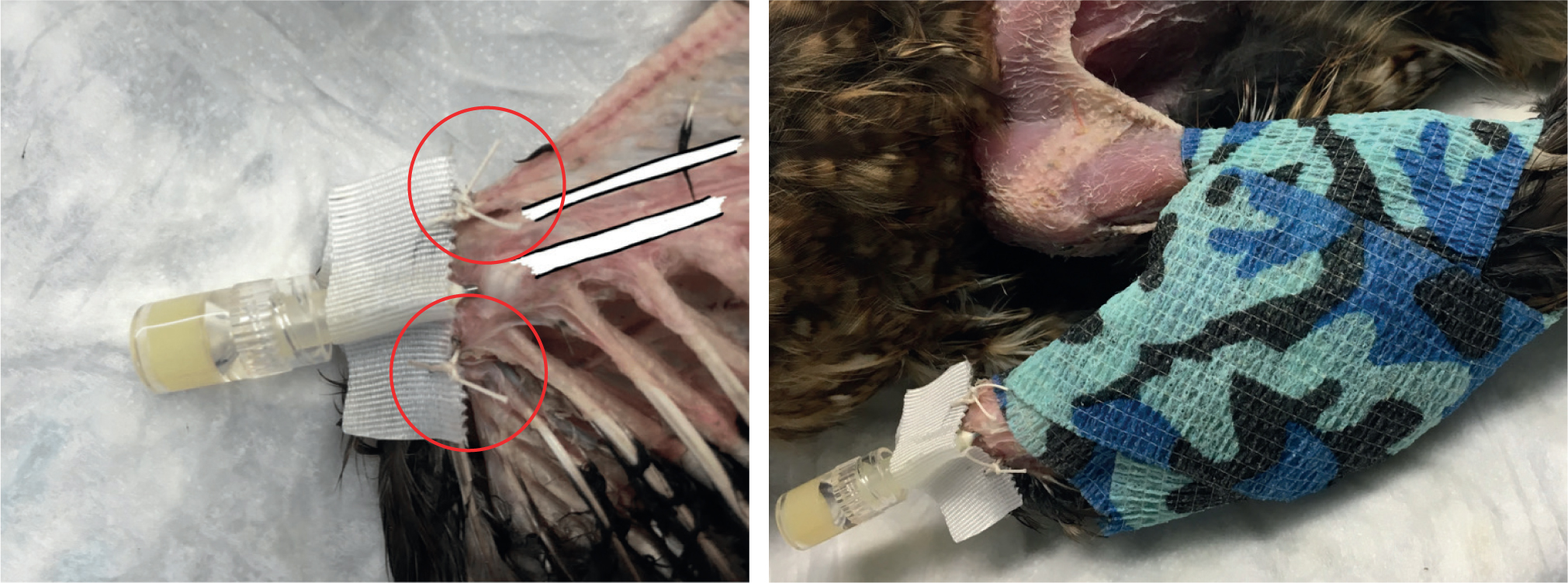

Secure the intraosseous catheter

Before using the IO catheter, it should be secured using surgical tape and stay sutures (Figure 8a). In smaller birds, tissue glue may provide a useful alternative to sutures. The hub of the hypodermic needle can be covered with a rectangle of tape to create ‘wings’ that can be secured using a simple interrupted suture on either side attached to the adjacent skin. The limb can then be immobilised by lightly bandaging using a figure-of-eight wrap (Figure 8b). The IO line must not remain in situ for longer than 3 days and should be flushed every 6 hours; the insertion site must be kept clean.

Conclusions

It can often be difficult to secure IV access in a small or collapsed dehydrated bird. Being able to place an IO catheter in the distal ulna can be an invaluable skill. Practicing this technique on cadavers gives the clinician confidence in correct catheter placement; competent placement will reduce the likelihood of complications. Placement should be performed aseptically and with appropriate anaesthesia and analgesia. Catheters placement should be confirmed before use and they should be appropriately secured and maintained once in place.

KEY POINTS

- An intraosseous catheter can be extremely useful when intravenous (IV) access is unattainable.

- Fluid therapy and most drugs normally used IV can be given by this route.

- Appropriate analgesia and anaethesia should be considered prior to placement.

- The distal ulna is a relatively accessible site for intraosseous catheter placement in birds.

- The position of the intraosseous catheter should be confirmed before use.

- Practicing on cadavers is recommended.