Traditionally, exogenous insulin treatment represented the mainstay in the management of diabetic cats to address hyperglycaemia and prevent ketosis (Sparkes et al, 2015). Previous trials with oral anti-hyperglycaemics like biguanides (metformin) (Nelson et al, 2004) or sulfonylureas (Nelson et al, 1993) as standalone treatments in diabetic cats yielded mostly unfavourable results and none were licensed for use in this species. Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are now revolutionising feline diabetology. Their use in humans with type 2 diabetes has shown efficacy in improving glycaemic control, beta-cell function and insulin sensitivity without increasing the risk of hypoglycaemia (Xu et al, 2022).

Mode of action

Cats with diabetes mellitus typically experience a condition that is comparable to type 2 diabetes in humans, and is characterised by relative insulin deficiency and insulin resistance (Gostelow and Hazuchova, 2023). Chronic high glucose concentrations lead to glucose toxicity with resulting pancreatic beta-cell desensitisation and dysfunction. Reducing hyperglycaemia by increasing renal glucose excretion may lead to improved insulin secretions without the need for insulin treatment.

The sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 is a transport protein located in the early proximal renal tubule and is responsible for approximately 90% of the reabsorption of glucose from the tubule back into the bloodstream. The remaining 10% are reabsorbed by a second transporter (sodium-glucose co-transporter 1, SGLT1) which is found in the distal aspect of the proximal renal tubule (Tahrani et al, 2013).

Velagliflozin is a highly selective SGLT2 inhibitor with only minor effects on the SGLT1. When the transporter is competitively inhibited, glucose reabsorption is reduced and glucosuria increased, resulting in lowered blood glucose levels. The action of the SGLT1 ensures sufficient glucose reabsorption to prevent clinical hypoglycaemia. When using this drug, there is an immediate onset of action (Hadd et al, 2023) and glucose concentrations will usually be in the target range within 1 week (Niessen et al, 2024). Reduced hyperglycaemia will lead to an improvement in the typical clinical signs of diabetes and allow the pancreatic beta cells to regenerate and increase endogenous insulin secretions that are essential to reduce ketogenesis. Improved insulin sensitivity with velagliflozin was suggested in one study on healthy obese cats (Hoenig et al, 2018).

Although glucose values may be in the reference range, ketone body formation can still occur if the patient is not able to produce enough endogenous insulin (Cook and Behrend, 2024). This will result in euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis, a life-threatening condition that will be discussed later in this article. This is also the reason why velagliflozin – or any other SGLT2 inhibitor – cannot be used as a sole treatment in diabetic dogs since dogs suffer from a type 1-like diabetes mellitus. This is characterised by a primary or secondary absolute insulin deficiency (Catchpole et al, 2008).

In a recently published European clinical trial using velagliflozin once daily as a standalone, the SGLT2 inhibitor was non-inferior to lente insulin (Caninsulin; MSD Animal Health) with treatment successes of 54% vs 42% at day 45 (Niessen et al, 2024). In this prospective, randomised, positive controlled field study, 116 (efficacy assessment) naïve and pre-treated diabetic cats were treated with either 1 mg/kg oral velagliflozin once daily (n=54) or twice daily lente insulin injections (n=62). By day 91, velagliflozin had been effective in lowering glucose and fructosamine levels and improving quality of life and polyuria/polydipsia, with significant improvements already occurring after 1 week of treatment (Niessen et al, 2024).

Available formulations in the UK

Senvelgo (Boehringer Ingelheim) is currently the only licenced SGLT2 inhibitor for use in cats in the UK. It is presented as a 15 mg/mL flavoured once-daily oral solution that can be administered either directly orally or with a small amount of food. The dose is fixed based on body weight, which renders the previous individual adjustments and dose determination for insulin therapy obsolete.

Additionally, there are several human formulations of other SGLT2 inhibitors on the UK market, including dapagliflozin (Forxiga), empagliflozin (Jardiance), canagliflozin (Invokana) and ertugliflozin (Steglatro). There are no medical advantages in using these medications in cats, but owners may be familiar with these drugs themselves. It is likely that other formulations will be licensed for use in the UK in the future.

Selecting the appropriate patient

In the UK, Senvelgo is licensed for use in newly diagnosed and insulin-pre-treated cats. However, not every diabetic cat is a suitable candidate for this treatment. Besides the typical clinical signs of diabetes (polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia and weight loss), the cat should be otherwise clinically healthy. They should not have any of the following clinical signs as part of their presentation: cachexia, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhoea, lethargy, dehydration or anorexia.

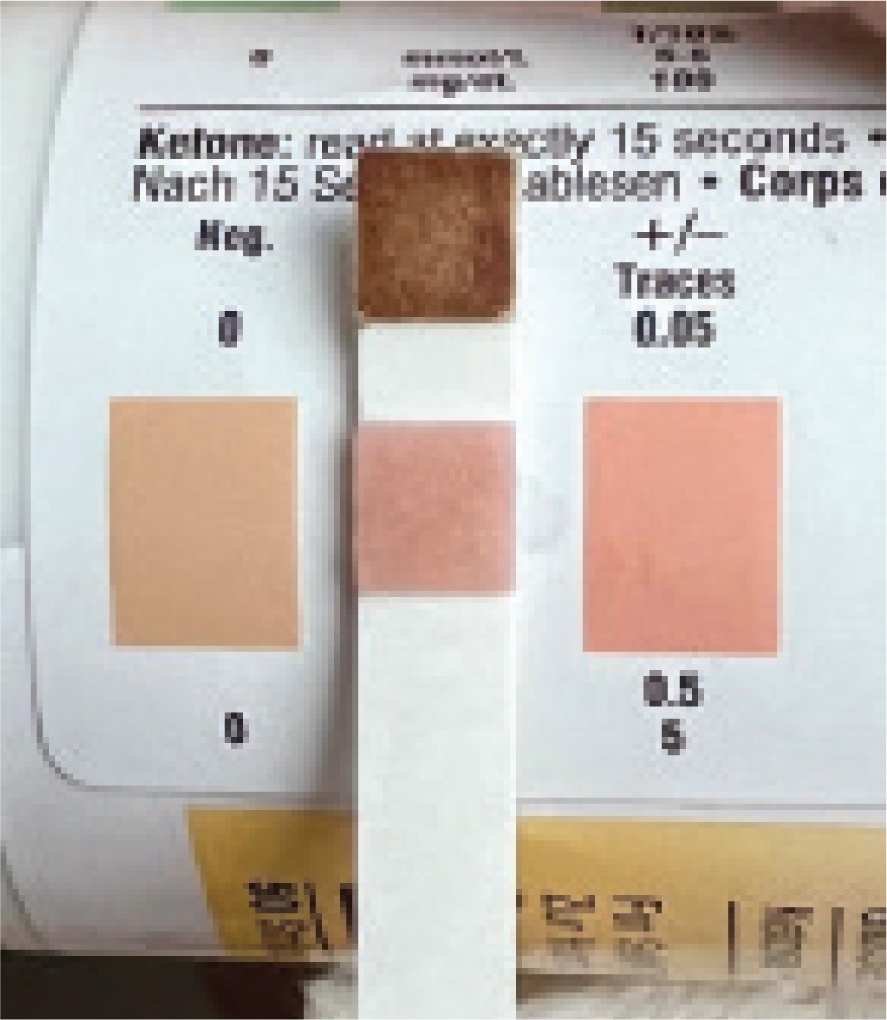

A history of previous episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis is a sign that the endogenous insulin production might not be sufficient to prevent significant ketone body formation and the development of further episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis, which is why SGLT2 inhibitor treatment in those cats is discouraged. If there is evidence of any ketonuria or increased serum betahydroxybutyrate levels at diagnosis, the cat should not be started on velagliflozin, but rather a treatment plan with insulin initiated. There is no universally accepted cut-off for betahydroxybutyrate levels in cats. While values up to 0.9 mmol/litre are not unusual for well-controlled diabetic cats (Weingart et al, 2012a), in one study, a cut-off of 2.44 mmol/litre had a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 87% for diagnosing diabetic ketoacidosis (Weingart et al, 2012a). In the authors' opinion, insulin treatment should be considered over SGLT2 inhibitors if blood betahydroxybutyrate concentrations exceed 1.5 mmol/litre, even if the cat is otherwise clinically well. It is important to use a ketone metre that is validated for veterinary use (eg Precision Xceed, Abbott (Weingart et al, 2012b) or Precision Xtra, Abbott (Zeugswetter and Rebuzzi, 2012)), as there are human ketone metres that have not been validated for cats.

Underlying conditions and comorbidities

Cats with underlying conditions (eg hypersomatotropism) or comorbidities (acute or chronic pancreatitis, advanced renal disease, hyperthyroidism) were excluded from the Niessen et al (2024) study. It seems logical that, provided that the cat is otherwise clinically well and routinely monitored for ketosis, SGLT2 inhibitors are a valid treatment option in cats with diabetes and underlying diseases that lead to secondary insulin resistance.

This seems especially true for diabetic cats with hypersomatotropism. Excess growth hormone leads to severe insulin resistance, while there is usually no absolute insulin deficiency because the pancreatic beta cells keep their ability to produce insulin, as demonstrated by the fact that most cats undergo diabetic remission after hypophysectomy (Fenn et al, 2021; van Brokhorst et al, 2021). With the action of SGLT2 inhibitors, glucotoxicity in those patients is significantly reduced and clinical signs improved, while the remaining beta-cell capacity is sufficient to prevent ketosis. In contrast to SGLT2 inhibitors, insulin treatment also puts these cats at risk for hypoglycaemia if the underlying condition is treated and the insulin resistance reversed (Fenn et al, 2021).

The safety and efficacy of velagliflozin has not been evaluated in cases of renal, hepatic or cardiac disease, and the general recommendation is to carefully assess suitability for treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors on a case-by-case basis.

Initiation of treatment

Velagliflozin is started by giving 1 mg/kg orally once daily at approximately the same time each day. There is no requirement for dose adjustment and if the blood glucose does not decrease within 1 week, then revision of owner compliance, additional diagnostics and insulin therapy is required.

There is currently a lack of data regarding which diet should be recommended for cats treated with SGLT2 inhibitors. High-protein, low-carbohydrate diets are currently recommended for diabetic cats on insulin treatment given their associations with improved glycaemic control and higher chances for remission (Sparkes et al, 2015). Unless precluded by comorbid conditions (eg chronic kidney disease), this nutritional strategy is likely also a good choice for SGLT2 inhibitor-treated cats.

Switching from insulin to velagliflozin

Although licensed in cats that have been pretreated with insulin and with similar published success rates so far (Niessen et al, 2024), the use of velagliflozin in stable diabetic cats who are already on insulin should be very carefully considered and is generally not encouraged by the authors. The chronic exogenous insulin supply will have suppressed the endogenous production, even if there was sufficient beta cell reserve left. By suddenly removing the exogenous insulin source, the risk for the development of euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis may be significantly increased, especially in the first days after withdrawal. Ketoacidosis was less common in naïve diabetic cats (5.1%) compared to insulin-pretreated cats (18.4%) in a US-based study on velagliflozin (Behrend et al, 2024).

If, despite this risk, a patient needs to be switched from insulin to velagliflozin, the evening dose of insulin should be skipped and the SGLT2 inhibitor started the next day. Velagliflozin is only licensed as a sole anti-diabetic medication and not as an adjunct with insulin, because concurrent treatment with both increases the risk for hypoglycaemia (Moulton et al, 2022), so this approach is not recommended. Since the glucosuric effect of the SGLT2 inhibitor may continue for 2–3 days after discontinuation, missing one dose of velagliflozin is not problematic. If switching from velagliflozin to insulin, then the first dose of insulin is administered 24 hours after the last dose of velagliflozin and for the next 24 hours a lower starting dose is advised (50%) followed by a normal starting dose (eg 0.2–0.4 units/kg every 12 hours for protamine zinc insulin; 1–2 units per cat every 12 hours for lente insulin).

Side effects and complications

The most important and concerning possible side effect of SGLT2 inhibitors is the occurrence of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis, which is characterised by the typical clinical and biochemical abnormalities of diabetic ketoacidosis but with normal glucose values. Seven percent of velagliflozin-treated cats in the recently published trial developed suspected euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis, with 3 of 4 events occurring in the first week after treatment start (Niessen et al, 2024). None of the cats in the study treated with lente insulin developed suspected diabetic ketoacidosis.

Normoglycaemia, or near normal glucose levels, is the result of the SGLT2 inhibitor action and they do not imply that the patient is able to produce enough endogenous insulin. If there is insufficient insulin produced endogenously or through exogenous treatment, then ketogenesis and subsequent ketoacidosis will occur despite SGLT2 inhibition (Cook and Behrend, 2024). Therefore, it is important not to exclude diabetic ketoacidosis in a diabetic cat being treated with an SGLT2 inhibitor that is clinically unwell based on a normal blood glucose concentration. Urine ketones or blood betahydroxybutyrate levels should be measured immediately, and if possible, the cat assessed for metabolic acidosis based on a venous blood gas analysis. If this is not possible, then the presence of ketones in a sick cat should be assumed to be because of acidosis. If euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis is confirmed, transfer to a centre with overnight hospitalisation facilities is recommended to facilitate the continuous care and treatment adjustment required. The SGLT2 inhibitor must be stopped immediately, and the cat transitioned to insulin – despite normoglycaemia. The insulin treatment will produce hypoglycaemia and so glucose supplementation must be initiated and at higher doses than for ‘normal’ diabetic ketoacidosis (Cook and Behrend, 2024). The insulin is essential to decrease ketogenesis. The treatment of euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis also requires appropriate fluid therapy, electrolyte supplementations and nutritional support. Once the euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis is resolved, then it may be possible to restart the SGLT2 inhibitor in individual cases, but this is generally not recommended since the cat is unlikely to have sufficient endogenous insulin production to prevent further episodes of ketogenesis in the future (Cook and Behrend, 2024). In some cats, temporary suspension of SGLT2 therapy and short-term insulin treatment might be necessary in situations that can predispose to diabetic ketoacidosis (acute illness, prolonged fasting, surgery). It is likely that veterinarians are going to have to get used to switching cats from velagliflozin to insulin and back and clear protocols for this will be needed.

The most frequent side effects that are reported with velagliflozin include loose faeces and diarrhoea (38%), positive urine culture (31%) and non-clinical hypoglycaemia (13%) (Niessen et al, 2024). Velagliflozin does have a minor effect on the SGLT1 which is also present in the small intestine, as well as the proximal renal tubule. The incomplete glucose absorption from the small intestine as a result of SGLT1 inhibition and subsequent osmotic diarrhoea explains the relatively high incidence of loose stools especially in the beginning of treatment (Hadd et al, 2023; Behrend et al, 2024; Niessen et al, 2024). This diarrhoea is usually self-limiting within 1 week or less and does not need further treatment, as long as the patient remains adequately hydrated (Niessen et al, 2024).

The glucosuric effect of SGLT2 inhibitors predisposes to urinary tract infections; however, this risk also applies to insulin-treated cats. Niessen et al (2024) found that the incidence of positive urine cultures was similar in cats treated with velagliflozin (31%) and lente insulin (27%). Urinary culture and sensitivity testing is recommended in every cat with clinical signs of lower urinary tract disease and/or pyelonephritis. Antibiotic treatment should be guided by culture and sensitivity testing.

The risk of clinically significant hypoglycaemia with SGLT2 inhibitor treatment is very low, because the SGLT1 in the kidney will still ensure sufficient glucose reabsorption to prevent symptomatic hypoglycaemia (Tahrani et al, 2013). Non-clinical hypoglycaemia has been observed relatively frequently, although less frequently than in lente insulin-treated cats (Niessen et al, 2024). Further side effects include polyuria/polydipsia, dehydration and initial weight loss because of the glucosuric effect of velagliflozin, and hypersalivation (Behrend et al, 2024; Niessen et al, 2024). All usually improve over time.

Monitoring

Previously well-established approaches for monitoring of feline diabetes have become obsolete when treating cats with SGLT2 inhibitors. Firstly, unlike with insulin treatment, there is no need for dose adjustments and secondly, blood glucose concentrations are expected to be within the normal range most of the time, while hypoglycaemia is very unlikely. This makes the generation of blood glucose curves or the use of continuous glucose monitoring devices unnecessary. Persistent glucosuria is to be expected, so monitoring of urine glucose concentrations is also unnecessary.

Monitoring cats treated with a SGLT2 inhibitor is primarily concerned with the early detection of possible complications, especially the occurrence of euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis. Monitoring for clinical signs of ketosis (anorexia, vomiting, diarrhoea, lethargy etc) as well as urine and blood ketone body formation is essential, especially in the first two weeks after starting treatment where the risk of this life-threatening complication is highest (Behrend et al, 2024; Niessen et al, 2024). Every owner should be provided with detailed information on what to look out for and alert the veterinarian immediately in case of any clinical deterioration. If any of these signs occur, the veterinarian must see and assess the patient immediately. Likewise, owners should be encouraged to monitor the cat's urine for ketone body formation at home and alert the veterinarian immediately if there should be any evidence of ketonuria. It is important to note that any ketones in urine are significant in a cat and a more sensitive and quantitative measure are blood concentrations of betahydroxybutyrate.

The patient should additionally be monitored for further common side effects, such as the occurrence of urinary tract infections (stranguria, haematuria) and routine urinalyses are advised every 3–4 months. Overall glycaemic control and general wellbeing should be assessed by regular physical examinations, including the determination of the cat's hydration status and body weight. Rapid and unexplained weight loss can indicate poor glycaemic control or the onset of ketosis (Cook and Behrend, 2024).

The manufacturer recommends the measurement of fructosamine for the overall glycaemic assessment of SGLT2 inhibitor-treated cats. This marker can also be useful in the differentiation between stress hyperglycaemia and uncontrolled diabetes when there are discrepancies between the measured spot blood glucose level (high) and the clinical signs. Suggested monitoring protocol for Senvelgo based on the manufacturer's recommendations can be found in Table 1.

| Every 1–3 days at home | Urine ketones |

|---|---|

| Day 7 at the clinic | History, physical examination including hydration status and body weight, assessment for ketones* |

| Day 14 at the clinic | History, physical examination including hydration status and body weight, assessment for ketones* |

| Week 4 at the clinic | History, physical examination including hydration status and body weight, assessment for ketones* |

| Every 3 months at the clinic | History, physical examination including hydration status and body weight, urinalysis, fructosamine, ketone assessment* |

ketone assessment* indicates measuring blood betahydroxybutyrate concentrations (preferable), or urine ketones

Remission

The currently published studies on SGLT2 inhibitors in diabetic cats did not assess for remission (Hadd et al, 2023; Behrend et al, 2024; Niessen et al, 2024). Although diabetic cats treated with SGLT2 inhibitors could be able to achieve remission based on the ability to achieve and maintain euglycaemia and normal fructosamine concentrations (Hadd et al, 2023; Behrend et al, 2024; Niessen et al, 2024), the detection of this will be more difficult because there will be no evidence of hypoglycaemia (unlike in insulin-treated cats that go into remission) when the need for exogenous treatment ceases. From a practical standpoint, there are two options in terms of remission: either the cat will be treated with the SGLT2 inhibitor lifelong or, usually after about 3 months, the treatment is discontinued and during the following days the cat very carefully evaluated for recurrent signs of diabetes. Increasing blood glucose concentrations and relapse of clinical signs must then prompt continuation of the SGLT2 inhibitor.

Conclusions

With the launch of Senvelgo, the first available oral antidiabetic treatment licensed for cats is on the UK market and offers a suitable new way of diabetic management for many uncomplicated diabetic cats. By inducing glucosuria, glucotoxicity is reduced and clinical signs improved. Its unique complications, especially the occurrence of euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis, must be known and understood by veterinarians when using this medication in order to select suitable patients and act promptly and appropriately if problems develop. This new treatment is easy to administer, simple to monitor and does not need dose adjustments and this means that more diabetic cats can be treated more easily.