Rabbits can experience a variety of endoparasites. In the clinical setting, rabbits will sometimes be presented for conditions directly linked to parasitism, or the parasites may be found as part of a clinical investigation and the clinician must decide whether or not they are clinically significant. This is not always simple and may depend on various factors, including the number of parasites, species of parasite, age of the rabbit and the immune status (including disease status) of the rabbit. With respect to the immune status, there may also be effects of husbandry system and social interactions, especially in a farmed or breeding setting.

This article discusses the internal parasites that may be commonly encountered in pet rabbits in the UK. It will cover their clinical effects, including direct clinical effects, and their influence and involvement in other disease processes. Encephalitozoon cuniculi is now classed as a microsporidian fungus and it is debatable as to whether or not it is a true parasite. However, it is an important pathogen of pet rabbits and is more worthy of a full article in its own right, so is not included here.

Otherwise, endoparasites are a comparatively unusual clinical issue in pet rabbits (aside from young animals or those in a large group (eg breeders) on small areas of long-term grazed land). Therefore, it is important to be aware of their potential for disease, but disease should not automatically be treated unless clinical signs genuinely correlate with the effects of that parasite, as their presence is not necessarily the cause of such signs. For example, if small numbers of intestinal coccidian oocysts are found in the normally-formed faeces of a thin adult rabbit with dental disease, clinical coccidiosis would be unlikely to be the cause of clinical signs and so coccidiostats would not be indicated.

Coccidia

Coccidian parasites are probably the most clinically significant of pet rabbits (Mäkitaipale et al, 2017).

Lifecycle and biology

There are two forms of coccidiosis in rabbits – intestinal and hepatic. The former may be caused by multiple Eimeria species, while the latter is caused by Eimeria stiedai (Halls, 2005). Both forms result from ingestion of infective oocytes and encyst in the intestinal wall. The intestinal form then enters the reproductive phase, resulting in oocytes being passed in the faeces, while the hepatic form encysts in the duodenal form. Sporozoites of the hepatic form then pass to the liver via the portal vein and lymphatics, where they enter reproductive phases with oocytes being passed into the intestine via bile. Both forms are common in the UK (Boag et al, 2013).

Clinical relevance and signs

The intestinal form of coccidiosis often causes no clinical signs. However, heavy infective loads may produce signs in young rabbits (Varga Smith, 2023):

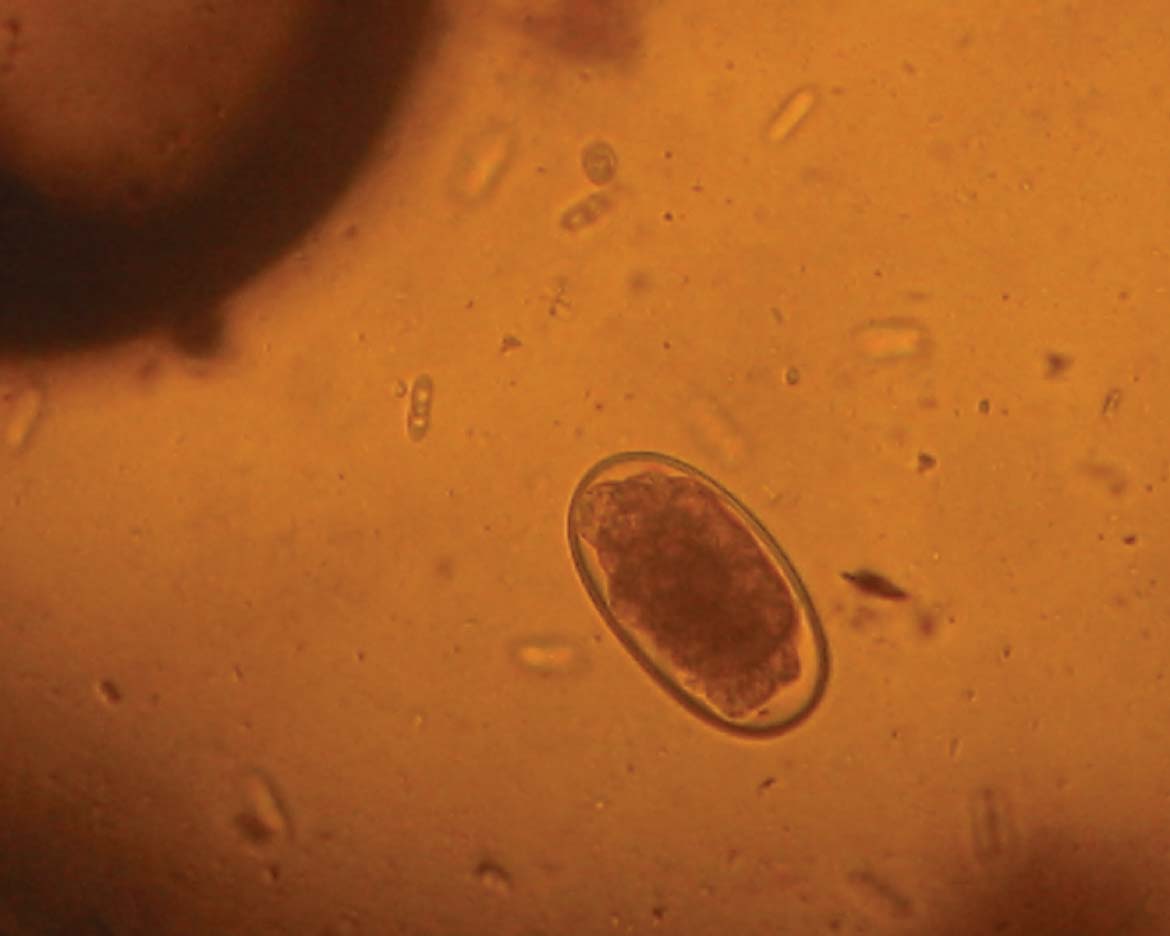

Diagnosis of both forms is done via identification of oocysts in faeces using wet preparations or standard faecal floatation techniques (Figure 1). However, the presence and number of oocysts does not necessarily correlate with clinical disease. Because the parasite breeds in cycles, it is possible to have large numbers of oocysts passed in light infections and very small numbers in heavy infections. The presence of oocysts in faeces must be correlated with:

Relevance to other pets and owners

Rabbit coccidians are unique to rabbits (and possibly other lagomorphs).

Treatment

Treatment is aimed at reducing the parasite burdens and allowing the development of immunity, rather than eradication of the parasite. The presence of oocysts in faecal screens at the end of treatment does not indicate treatment failure unless clinical signs have not resolved. Diclazuril is a licensed coccidiostat for rabbits for use in-feed in the farm situation; most of the drugs described here are for off-license use in the individual or very small group pet situation, where in-feed dosing is not appropriate and likely to result in incorrect dosing. When dealing with coccidiosis in the pet situation or, particularly, in the shelter situation, clinicians must be aware of licensed drugs and determine whether these are appropriate before considering off-license drugs used under the cascade prescribing system with owner consent). Where there are clinical signs, symptomatic treatment is required (typically, fluid therapy and supportive feeding). Otherwise, the following may be considered:

Diclazuril may be used at 500 g/ton of feed in the event of outbreaks for large breeders or fattening unit (in the latter case, a minimum meat withhold time of 2 days must be applied). To do this, a Medicated Feedingstuff prescription must be given to the supplier who is authorised to mix this product.

Prophylaxis

Prophylaxis is rarely indicated in the pet situation, other than treatment of asymptomatic animals in contact with those showing clinical signs. In these animals, subclinical disease is likely, so they may receive the same treatment regime as the affected rabbit(s). However, in the shelter or pet shop situation, prophylactic therapy is much more likely to be needed given the larger number of animals, turnover of animals and mixing of animals from different sources and of differing ages.

The use of the licensed in-feed additive diclazuril should be considered where numbers justify this. Otherwise, off-license drugs may be used with owner consent. Prophylactic drugs may be used in the following ways:

In any event, it is vital that new rabbits undergo a period of quarantine before entering the main group. This allows for testing and treatment as required, and is especially important as stressors are likely to result in increased oocyst excretion (based on other species).

Cestodes

Adult intestinal tapeworms are reported in wild rabbits in Europe (Allan et al, 1999) but are rarely significant in pet rabbits (Wright, 2018), other than when pets are kept outside and may mix with wild rabbits. However, rabbits are intermediate hosts for larval forms of two species, Taenia pisiformis and Taenia serialis. These present as thin-walled fluid-filled cysts.

Lifecycle and biology

The adult form of these tapeworm species is found in the gut of dogs and foxes – rabbits are infected by ingesting faeces from infected dogs or foxes. Cestode eggs hatch in the rabbit intestine and larvae pass via the gut wall to the portal and systemic circulation. Here, they encyst:

Clinical relevance and signs

There are typically few clinical signs, unless there are multiple cysts and reactions within the liver or the muscle cysts are large and/or multiple, resulting in compromised mobility. However, owners do find the subcutis cysts unsightly and are especially keen for treatment when they are aware of the cause.

Diagnosis

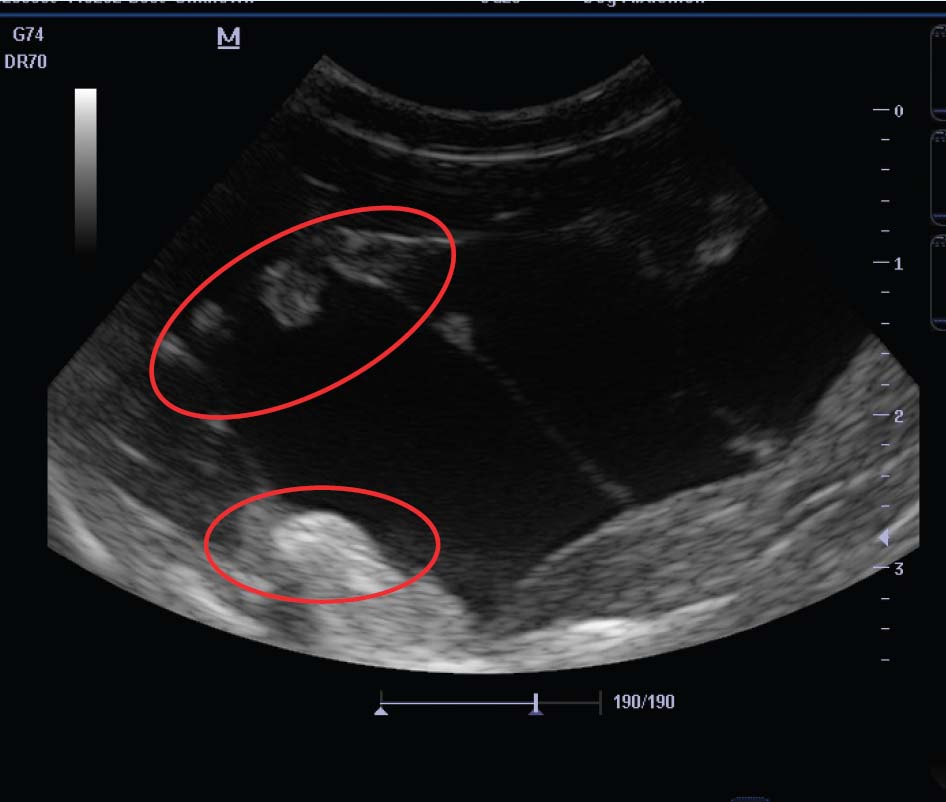

Diagnosis may be based on appearance and rule out of other causes of subcutaneous swellings, especially abscesses and haematomas. Typically, they are soft, fluctuant and do not feel as hard as abscesses. Faecal sampling would be inappropriate here, as adult (intestinal) worms are not found in this species. More definitive diagnosis is achieved by:

Relevance to other pets and owners

Unless the rabbit (and cyst) is eaten, there is no direct risk to the owner or to other pets, as the rabbit will not be shedding infective forms. However, ingestion of T. serialis proglottids and eggs may result in cyst formation (coenuriasis) in humans – the presence of cysts in the rabbits indicates the presence of these eggs in the environment and, therefore, potential human risk.

Treatment

Treatment using praziquantel is rapid and effective. This is given at 5–10 mg/kg orally twice, 2 weeks apart. Typically, canine or feline tablets may be crushed, mixed with water and given as a suspension via syringe. Occasionally, an inflammatory response may be seen to the reducing cyst. Owners should be warned about this because it may cause clinical signs, especially if the cyst is in a sensitive position (eg near the spine). In these cases, if there is concern and a single cyst, surgical removal of the cyst may be a valid option. Before removal, ultrasound (or computed tomography) may be used to delineate the cyst and any cyst ‘buds’.

When treating these cysts, it is important that the rabbit is removed from contaminated ground and that dogs or foxes are excluded from the area where the rabbit is kept. Foodstuffs should also be thoroughly checked for faecal contamination and the source changed if the risks are high (eg foraging for grass/weeds from public areas). This will reduce the chances of re-infection.

Prophylaxis

Rabbits should not be fed faeces-contaminated foodstuffs, and care must be taken that grazing areas are not contaminated with dog or fox faeces.

Nematodes

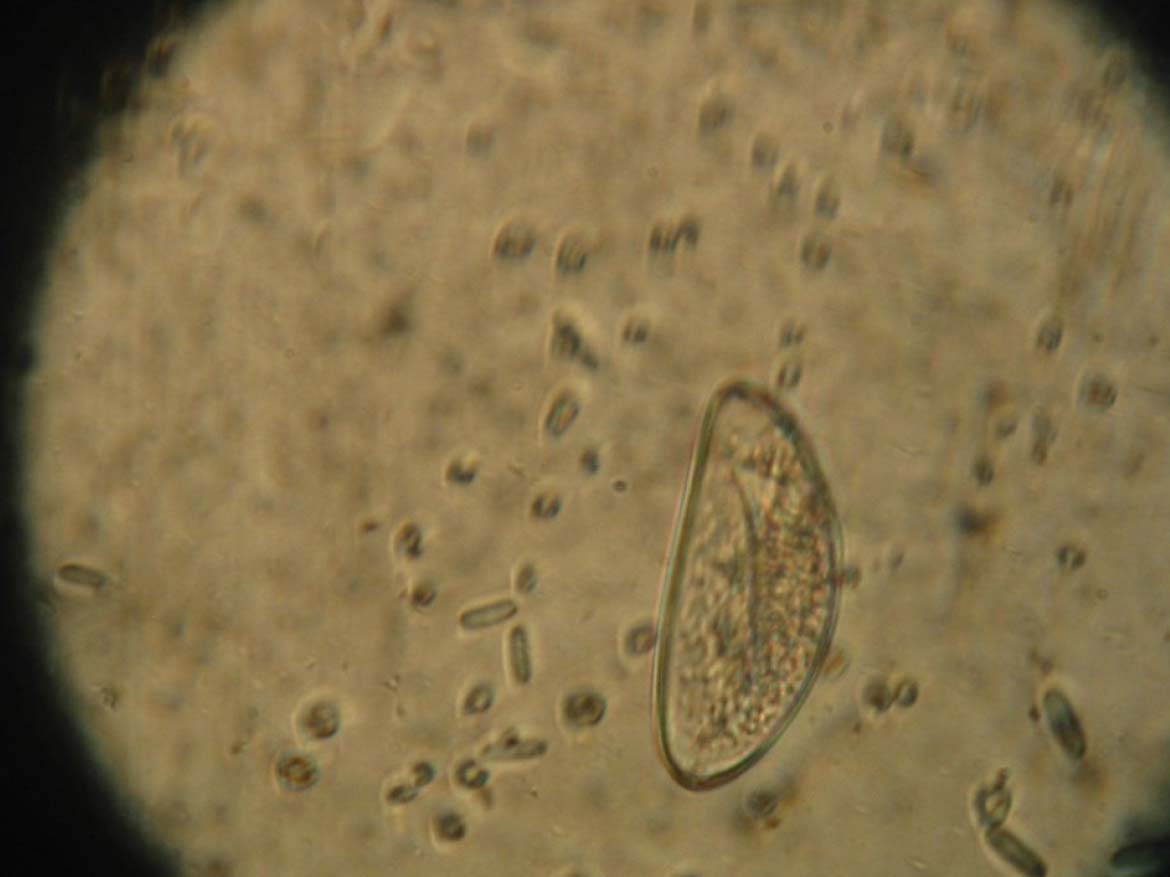

While there are a range of nematode species that infect wild rabbits, most are rare and of little significance in pet rabbits. However, two are worthy of awareness by the clinician – Baylisascaris procyonis and Passalurus ambiguous (Figure 5) (Baker, 2007).

Baylisascaris procyonis

Lifecycle and biology

Baylisascaris is more of a clinical issue in pet raccoons which are definitive hosts (Kazacos, 2001). However, as in humans, infective eggs may be ingested by rabbits resulting in extensive larval migration, including to the central nervous system. This may result in disease. The parasite has been detected in raccoons in Europe (Davidson et al, 2013; Lombardo et al, 2022); as raccoons have become more popular as pets in the UK, this is potentially also an issue in mixed-pet households.

Clinical relevance and signs

This should be considered among the differential diagnoses of any non-specific illness in rabbits where there are also pet raccoons in the household. In particular, it should be among the differential diagnoses where there are neurological signs, including ataxia and circling.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is done via serology, but this test is not always available. Otherwise, the finding of Baylisascaris eggs in pet raccoon faeces and signs in a rabbit in the same household may be taken as ‘smoking gun evidence’ – an appropriate response to treatment will reinforce this.

Relevance to other pets and owners

Infected rabbits pose no risk to humans, but humans can also experience larval-related disease in the same way as rabbits. As such, testing and treatment of rabbits will also be necessary as part of any household control where there are infected raccoons and, particularly, where there has been human disease. It is important to regular perform faecal checks on pet raccoons to screen for this parasite.

Treatment

Fenbendazole at 20 mg/kg orally every 24 hours for 3 days should be effective against larval disease.

Prophylaxis

Prevention is done by stopping the ingestion of infected raccoon faeces. Pet raccoons should be regularly screened and treated if necessary, because of the zoonotic aspects of baylisascariasis.

Passalurus ambiguous

Pinworm is regularly found in pet rabbits, but it is rarely of clinical significance.

Lifecycle and biology

The lifecycle is direct (rabbits are infected by eating eggs passed in faeces) which is why pinworm can reproduce and amplify rapidly in colonies.

Clinical relevance and signs

Very few clinical signs have been directly ascribed to or associated with pinworm infection. However, it has been suggested that poor thrift has been associated with heavy infection. In the author's experience, clinical signs have been seen on three occasions – all were in large groups of pet (or zoo) rabbits where the pasture had been extensively grazed for many years, and there was mixing with wild rabbits. All affected animals were thin, and in one case, there were sporadic deaths as a result of secondary bacterial infection. In all cases, clinical signs resolved with anthelmintic treatment and a change of pasture.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is done by finding eggs in faeces (Figure 6), or adult worms in large intestinal contents.

Relevance to other pets and owners

This parasite does not transmit to other species.

Treatment

There are a range of licensed anthelmintics that may be effective at standard dose rates via oral or percutaneous routes. Ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg percutaneously), piperazine (200 mg/kg orally) and fenbendazole (50 ppm in feed, or 20 mg/kg orally; also licensed for E. cuniculi treatment) are all licensed in rabbits in the UK (Hedley, 2023).

Prophylaxis

It is frequently recommended to use fenbendazole as part of regular control (this is licensed for control of Encephalitozoon cuniculi and intestinal worms). However, the absence of clinical disease from pinworm infections would suggest drug prophylaxis is unnecessary for this purpose. Good substrate hygiene (indoor rabbits) or rotation of grazing (outdoor) and non-mixing with wild rabbits would be more appropriate in preventing build up of large numbers of parasites.

Conclusions

The parasites discussed in this article are unusual causes of disease in UK pet rabbits, but may be encountered by clinicians while investigating clinical signs. An understanding of the significance of finding these parasites will aid in deciding appropriate therapy.