Cutaneous adverse food reactions manifest in the skin. The main clinical sign is pruritus, and reactions can involve the immune system (food allergy) or not (food intolerance) (Mueller and Unterer, 2018). Dietary management is important for both the diagnosis of this condition and for long-term management. The latter consists of feeding complete diets avoiding individual triggers, which can be identified during the diagnostic phase.

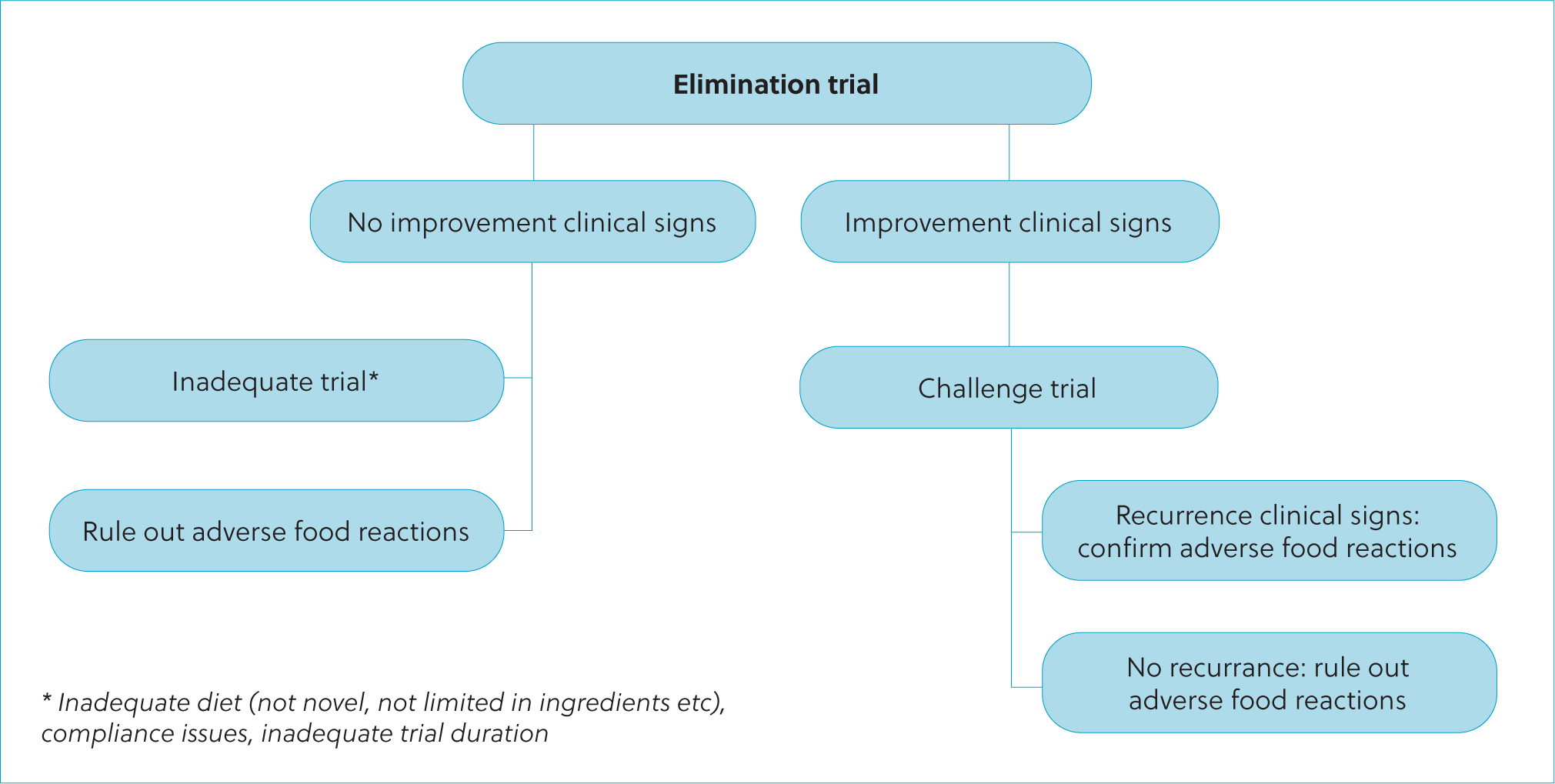

The gold standard diagnostic of cutaneous adverse food reactions consists of an elimination and challenge dietary trial (Jackson, 2001; Mueller and Unterer, 2018; Paterson, 2021) (Figure 1). The elimination phase consists of exclusively feeding the patient a diet that they have never been exposed to or with reduced allergenicity (‘elimination diet’) for at least 8 weeks (Olivry et al, 2015). The use of steroids at the start of the trial has been proposed to be useful in reducing the length by controlling the initial inflammation and pruritis (Favrot et al, 2019). After that, if the pruritus has not improved, cutaneous adverse food reactions can be ruled out and further investigations are required. The patient could still have a cutaneous adverse food reaction if the elimination diet was not adequate (for example, not novel for the patient, or containing undeclared ingredients), not fed for long enough or if there were compliance issues, such as use of treats, flavoured supplements, food scraps and the like. Those patients whose pruritus has improved would move to the challenge phase, where the patient is exposed to different ingredients or the previous diet. Using individual ingredients instead of a complete diet is helpful, as this will allow identification of the triggers to avoid. Multiple ingredients should be offered at one time, as patients can react to more than one ingredient (Jeffers et al, 1996). If the clinical signs reoccur, a cutaneous adverse food reaction can be confirmed.

The time taken to respond to the challenge for each ingredient varies, with some reacting on the first day (Olivry and Mueller, 2020; Shimakura and Kawano, 2021) and other animals taking longer (up to 7 days in cats and 14 days in dogs; Olivry and Mueller, 2020). Other diagnostic tests, such as serum, hair or saliva testing of immunoglobulins, are not yet a reliable substitute (Hagen-Plantinga et al, 2017; Mueller and Olivry, 2017; Bernstein et al, 2019; Coyner and Schick, 2019). Bethlehem et al (2012) suggested that a positive result in patch testing or specific serum immunoglobulins G and E does not correlate well with the gold standard, but negative results indicate the ingredient is likely tolerated. Therefore, while this could be used to select appropriate elimination diets, the dietary trial still must be performed.

Performing an elimination and challenge trial is an important part of the workup of pruritic patients. This is a cumbersome process, as it is long and can be affected by lapses in compliance. Moreover, choosing the right elimination diet is a key aspect of the diagnostic process and it can be complicated by several factors, including the large number of diets in the market (and homemade recipes) available to choose from. This review will focus on the characteristics of different types of elimination diets and provide tools on how to choose among them.

Elimination diets

The diets used for the elimination part of the trial are called elimination diets. These are sometimes referred to as ‘hypoallergenic’, but as allergenicity of a diet depends not only on the diet but also on the patient and what they have been exposed to, this term can be misleading. In Europe, the legislation for veterinary diets (PAR-NUTs, or feeds for a PARticular NUTritional purpose; European Union Commission, 2020) does include a ‘reduction of ingredient and nutrient intolerances’ nutritional purpose, and the described nutrient requirements include selected and limited number of protein source(s), and/or hydrolysed protein source(s) and/or selected carbohydrate source(s). There are diets on the market claiming to be ‘hypoallergenic’ that do not meet these nutritional requirements; therefore, it is important for the veterinary health care team to check the available commercial options to maximise the chances of the trial succeeding.

Limited ingredients

When assessing the clinical response of a patient to a diet, it is important that the ingredients are as limited as possible. Usually, this means one protein source (occasionally two) and one carbohydrate source (plus oils and supplements providing micronutrients for complete diets). A patient offered a diet with multiple ingredients will be exposed to multiple potential antigens and the likelihood that all these ingredients are novel to the patient also decreases.

Reduced allergenicity: novel ingredients vs hydrolysed protein

There are two main strategies to reduce the allergenicity of the elimination diet: choosing something novel to the patient or using a diet based on hydrolysed protein. In humans, food allergens are mainly glycoproteins with a molecular weight of 10–70 kDa (Verlinden et al, 2006). A minimum protein size is needed to cross link two or more immunoglobulin E molecules to trigger mast cell degranulation in certain types of food hypersensitivity, and the hypothesis is that reducing protein size prevents this cross-linkage (Cave, 2006). However, this is extrapolation, as data on canine and feline food allergens are scarce.

Novel ingredients

Adverse food reactions appear after exposure to the offending ingredient; therefore, patients should not react to ingredients to which they have not been exposed. The first veterinary diets for the purpose of diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous adverse food reactions were based on this strategy; this is still commonly used, although the ingredients used in commercial diets for this purpose have changed over the years. The ingredients used in pet food change constantly depending on cost, availability and market trends. The appearance of new pet foods with ingredients that were not commonly used in the past (therefore, more likely to be novel) means that novel ingredient elimination diets have to be adapted relative to the type of ingredients used in the market.

It is important to note that an ingredient is novel relative to the individual patient, and a complete diet history should be performed to identify the ingredient exposure in each case. This can be challenging, as the caregivers might not remember all the foods that their pet has been exposed to (including commercial complete diets, treats, flavoured supplements, table foods etc), and some pet foods do not report the specific ingredients included. European Union legislation allows diets to be labelled by category (for example ‘meat and meat by-products’), which sometimes renders the task of identifying exposures impossible. Therefore, it is not always possible to know what ingredients might be novel. It is recommended to choose limited ingredient diets that at least avoid commonly reported triggers for cutaneous adverse food reactions in dogs (beef, dairy, chicken) and cats (beef, chicken, fish) (Verlinden et al, 2006; Mueller et al, 2016). These might not reflect a higher allergenicity of these protein sources, but rather their common use in pet food formulations. For example, Verlinden et al (2006) identified beef, dairy and wheat as the three most common trigger ingredients for cutaneous adverse food reactions in dogs; in contrast, Mueller et al (2016) noted that chicken was the third most common, after beef and dairy. This could reflect the increased use of chicken as a main ingredient in pet food in the last years, thus increasing the likelihood that pets may be exposed to it. This has also been reflected on the type of ingredients used for elimination diets which commonly used lamb in the past. However, as lamb became a common ingredient in pet food, current commercial diets rarely use it, preferring more exotic (that is, rarely used in pet foods) ingredients like venison or rabbit. In the author's experience, there has been also a recent increase in the use of insect-based diets for this purpose.

Another potential concern regarding the choice of novel ingredients is the possibility of cross-reactivity as a result of similarities in antigens of related foods, but there are no data in dogs and cats demonstrating that this is a significant problem. Jeffers et al (1996) noted that dogs that reacted to beef did not react to dairy, and the same for dogs which reacted to wheat did not react to soy and vice versa.

Commercial vs homemade

Home-prepared diets can also be used in the elimination trial. These can be complete, providing all essential nutrients (of which there are around 40; National Research Council, 2006), or not. A non-complete home-prepared diet consists usually of two ingredients (a protein and a carbohydrate source). A complete home-prepared diet usually includes one or more fat sources (to meet essential fatty acid requirements) and supplements on top to include micronutrients that are not provided by the main ingredients.

There are some common disadvantages to using home-prepared diets in pets (Villaverde and Chandler, 2022), especially if they are not complete. Commercially veterinary elimination diets are complete for adults, in some cases even for growth, and are convenient and easy to use. Dry commercial diets are also usually more cost-effective compared to home-prepared diets (Vendramini et al, 2020), especially if the home-prepared diet has to be made with rare ingredients, which can also be hard to source in grocery stores or even butchers, compared to more commonly used meats. Finally, home-prepared diets cannot be tested, while commercial diets can, both to ensure nutritional adequacy and clinical efficacy.

Unbalanced homemade diets can result in nutrient deficiencies or toxicities that can have negative consequences for the health of the patient in the medium–long term (National Research Council, 2006). The degree and severity of these imbalances depends on the nutrient(s) involved, the degree of deficiency/excess, the nutritional status and life-stage of the patient and the length of time an unbalanced diet is fed. For example, calcium deficiency in puppies can manifest in 2–3 weeks, whereas in adult dogs it might take months to years before clinical signs are observed (National Research Council, 2006). In the author's opinion, when a homemade diet is desired, it is best if the diet is balanced for long-term use, even if only used during the elimination phase.

Commercial elimination diets based on novel ingredients also have drawbacks. While available diets can use ingredients not commonly used in pet food, these are not always novel to the individual patient; therefore, these patients will require hydrolysed diets or a home-prepared diet. In some cases, it is possible that a patient does not improve with a commercial uncommon ingredient diet but there is improvement when using a home-prepared diet with the same main ingredients. The reason for this is unknown, but it has been proposed that the inclusion of additives could play a role (Gaschen and Merchant, 2011). The presence of undeclared antigens in commercial diets has also been reported (Raditic et al, 2011; Ricci et al, 2013; Willis-Mahn et al, 2014; Fossati et al, 2019), potentially because of cross-contamination during the manufacturing process, but there are no data to suggest that home-prepared diets would have a lower risk for this problem. For these reasons, some clinicians prefer a home-prepared diet for the diagnostic of cutaneous adverse food reactions (Mueller and Unterer, 2018).

In the author's opinion, a veterinarian board certified in nutrition (in Europe, a European Board of Veterinary Specialisation Specialist in Veterinary and Comparative Nutrition) should be consulted to obtain a recipe customised for the patient. This ensures that the diet meets the nutrient and energy needs of the patient, using ingredients identified as novel (or likely novel) after extensive review of the diet history and checking that the caregivers can source and cook them. Moreover, the specialist can take into account the presence of any nutrient-sensitive comorbidities such as canine pancreatitis, which might require a low-fat diet, chronic kidney disease or certain types of urolithiasis. Recipes from the internet have multiple nutritional inadequacies (Stock-man et al, 2013; Wilson et al, 2019) and are not custom-made for each case. If the choice is made to feed an unbalanced home-prepared diet (using only one protein and one carbohydrate source) for diagnostic purposes, it should meet at least the energy and protein needs during the trial, and only be attempted in otherwise healthy adult animals. The patient should maintain weight and a good body and muscle condition throughout.

This diet should not be fed for longer than the 8 weeks needed for the trial, given the risk of nutritional deficiencies or toxicities. The author recommends not using such a diet, even in the short term, in patients with high energy and nutrient demands, such as reproducing or growing animals (National Research Council, 2006). If in doubt, the author recommends consulting a board-certified veterinary nutritionist for assistance. Raw elimination diets (either home-prepared or commercial) have multiple associated risks (Freeman et al, 2013), including those related to micro-biological safety of pets and humans. This author does not use raw diets given those risks and the lack of clear demonstrated benefits.

Hydrolysed protein diets

Reducing the size of the protein by hydrolysis results in a reduction of the allergenicity of the diet (Cave and Guilford, 2004; Puigdemont et al, 2006). There are several diets in the market using this strategy, based on hydrolysed chicken, soy, feathers or salmon (among others). These diets vary in the average size of the hydrolysate, but also in their nutritional profile, texture, palatability, life stage, cost and availability. They also differ in the carbohydrate source used, with some using purified starch (flour where the protein fraction is removed), and others using rice or more uncommon sources (potentially novel), such as potatoes or peas. The carbohydrate source is also a potential source of allergens, which is why these diets used purified starch, or potentially novel sources, or rice (which is not a common allergen in dogs and cats; Mueller et al, 2016).

The main advantage of this strategy is that it can be used even when the diet history is unknown, or when the patient has been exposed to multiple ingredients and identifying something novel is not possible. Clinical studies using hydrolysed protein diets in pets with cutaneous adverse food reactions have shown that the use of these diets can result in improvement of clinical signs (Loeffler et al, 2004; Olivry and Bizikova, 2010; Bizikova and Olivry, 2016; Matricoti and Noli, 2018; Weemhoff et al, 2021; Szczepanik et al, 2022).

However, some animals that have a negative reaction to the native (intact) protein can also react to its hydrolysate, and might not improve with such diets, which can be related to the size of the hydrolysed particle (Cave, 2006; Bizikova and Olivry, 2016). Anecdotally, palatability can be variable and mixing in other foods to make it more appetent can interfere with the trial. Moreover, these diets are also costly.

Choosing the best option: nutritional assessment

All patients should receive a nutritional assessment (World Small Animal Veterinary Association Nutritional Assessment Guidelines Task Force members et al, 2011), to assess the animal, diet and environment, and identify any nutritional risk factors present. This information will allow the recommendation of the best feeding plan, including diet choice, daily allowance and feeding method.

Diet choice

A limited ingredient elimination diet, be it based on novel ingredients or hydrolysed protein, is indicated for the first step in the diagnosis of a cutaneous adverse food reaction. The choice between hydrolysed protein diets and novel strategies (and commercial vs home-prepared diets in the latter case) is going to vary in each case depending on different factors like species and life stage, availability, cost, palatability, diet history (known or unknown), co-morbidities and client preferences (Table 1).

| Veterinary hydrolysed protein diets | Novel ingredient diets | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Veterinary commercial uncommon ingredient diets | Home prepared diets with novel ingredients | ||

| Advantages | Easy and convenient to use |

Easy and convenient to use |

High control of ingredients |

| Disadvantages | Not all patients might respond if reactive to native protein |

Require known complete diet history |

Expensive and time-consuming |

Veterinary elimination diets can differ in many aspects, including nutritional profile. Asking the manufacturer for their product guides is recommended, as those documents provide additional information (compared to the label) and often on a calorie base (in grams or milligrams per 100 or 1000 kcal of metabolisable energy), which allows for direct comparison between products, independently of their moisture content and energy density. Sometimes, it is useful to know the macronutrient (protein, fat and carbohydrate) profile or the content of certain nutrients in the diet of choice, for example when the animal has nutrient-sensitive comorbidities.

Dry and wet foods can both be used. Dry foods are more calorie dense (which is beneficial in underweight animals, can be used in food dispenser toys and are more cost effective. Wet foods can be more palatable for some patients and provide more water, which can be of interest in certain situations, such as in patients with a history of urolithiasis. However, there are not a lot of options in the hydrolysed protein category.

If using a commercial product, choosing a manufacturer with good quality control measures is essential. Using veterinary products from reputable brands that invest in science and publish their clinical trials will minimise the risk of undeclared antigens present in the diet, which could affect the trial. It is known that diets with ‘hypoallergenic’ claims (especially diets marketed for healthy pets) can have undeclared antigens as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or polymerase chain reaction testing (Raditic et al, 2011; Ricci et al, 2013; Willis-Mahn et al, 2014; Horvath-Ungerboeck et al, 2017; Fossati et al, 2019). It is not known whether small amounts of undeclared ingredients as a result of normal cross-contamination can really affect the result of the elimination trial, but at this time, it is sensible to choose diets that avoid or minimise that risk. Companies need to manufacture these diets in specific ways to prevent this issue (including separate handling of the raw materials, producing the food separately from others or after a deep cleaning etc) and they should analyse the final product to confirm that no undeclared ingredients are present. It is always important to check the ingredient list, as some diets might stress the presence of an uncommon protein source, but have other sources present as well.

It is also critical to ensure that the elimination diet is the only thing that the patient consumes. Items that might interfere with the trial include flavoured medications or supplements (Marquez et al, 2022), treats, dental chews, toothpaste and others. It is important to ensure that this has been communicated to and understood by the pet caregivers. Some pet food companies have commercial treats made with the same ingredients as their hydrolysed diets. If giving a novel ingredient diet, treats using the same ingredients could be considered, but these should be assessed the same way as the main diet, as they can also provide undeclared antigens. Alternatively, owners can buy the same meat as the commercial product and cook it at home for a treat.

Daily allowance and feeding method

When using commercial products, label instructions can be followed or a formula to estimate requirements can be used (National Research Council, 2006; Hand et al, 2010; European Pet Food Industry Federation, 2020). If using a formula, the estimated energy requirements (in kcal of metabolisable energy per day) need to be divided by the energy density of the diet of choice (kcal of metabolisable energy per gram). The latter can be obtained by calling the manufacturer or checking their website, if it is not reported on the label. The formulator should have this information for home-prepared diets. Formulas to calculate energy requirements and label recommendations are extrapolated from a population and have a high associated error when applied to individuals; as such, they should be just used as a starting point. The daily allowance should be adjusted in 10% interval every 2 weeks to meet the weight goals of the patient (for example, weight stability in adults with ideal or high body condition, or weight gain in adults with a poor body condition).

A more precise way to estimate energy needs in patients whose weight remains consistent is to calculate current energy intake via a complete diet history. In these cases, there is no need to use a formula. If unbalanced items (such as approved treats) are given, these can provide a maximum of 10% of the daily kcal, reducing the main diet accordingly to avoid unbalancing the diet and undesired weight gain. Portion control is an adequate feeding method in most cases (one or multiple meals per day), but lean patients that self-regulate their food intake or that are thin with a picky appetite can be free-fed.

Follow up

The caregivers can record the daily information, like food in-take, degree of pruritus and such, so the efficacy of the elimination diet in reducing the clinical signs can be accurately assessed after the duration of the trial. If the clinical signs have not improved and compliance was adequate, cutaneous adverse food reactions can be ruled out; however, different dietary strategies have limitations, as discussed (such as presence of undeclared ingredients or some patients reacting to the hydrolysate) and in this case, a second trial can be considered with a different dietary strategy or a different source of the protein hydrolysate.

In patients that improve, the challenge phase can be instituted to confirm the diagnosis and identify the triggers. It is important to note that environmental allergies can be seasonal, and interpretation of the elimination trial can be compromised if it coincides with times of a reduction in environmental allergens. The challenge phase is essential to confirm the diagnosis; if the improvement was because of environmental changes, the patient will not worsen when challenged. In any case, choosing the timing of the feeding trial is important, especially in patients where the caregivers report a seasonality to the pruritus. Long-term management then requires choosing a diet that avoids those triggers. While veterinary elimination diets are complete and can be used long-term, it is sometimes possible to identify tolerated maintenance diets, as there is no need to be as strict during this phase compared to the initial elimination diet.

Conclusions

Cats and dogs may have allergic reactions to their diet that can manifest in the skin. Elimination diets and diets using novel proteins can be used to determine which foodstuff is responsible for these reactions, although these diets may come with their own problems. Homemade diets have the benefit that owners will know exactly what their pet is eating, but these may not be as nutritionally balanced as a commercial pet food, potentially leading to other health problems in the long term. Any dietary changes made with the aim of determining the cause of an cutaneous reaction should be undertaken carefully, and with the advice of a board-certified nutritionist, where appropriate.