The guinea pig (Cavia porcellus), a social, diurnal rodent, once a laboratory animal, is now a widely kept companion animal. The frequency of guinea pigs presenting in small animal practices is increasing and veterinarians now face similar surgical challenges as in dogs and cats.

Tumours are one of the most common reasons for presentation and owners expect to have the best treatment options available. The second most common tumour group in guinea pigs are those of the skin and subcutis, making up around 15% of reported cases (Greenacre, 2004).

Guinea pigs are herbivorous and use their lips to grasp the plant material they eat (Mentré and Bulliot, 2014). Thus, the presence of the lips is very important for feeding and survival in these animals. Guinea pigs have 23 whiskers on each side of their face, which are located above the lips. Their mystacial pad is very similar to that of nocturnal rodents, which suggests the important role of whiskers: they protect the eye, are part of the sensory apparatus, and are involved in social behaviours in guinea pigs (Grant et al, 2017).

Case presentation

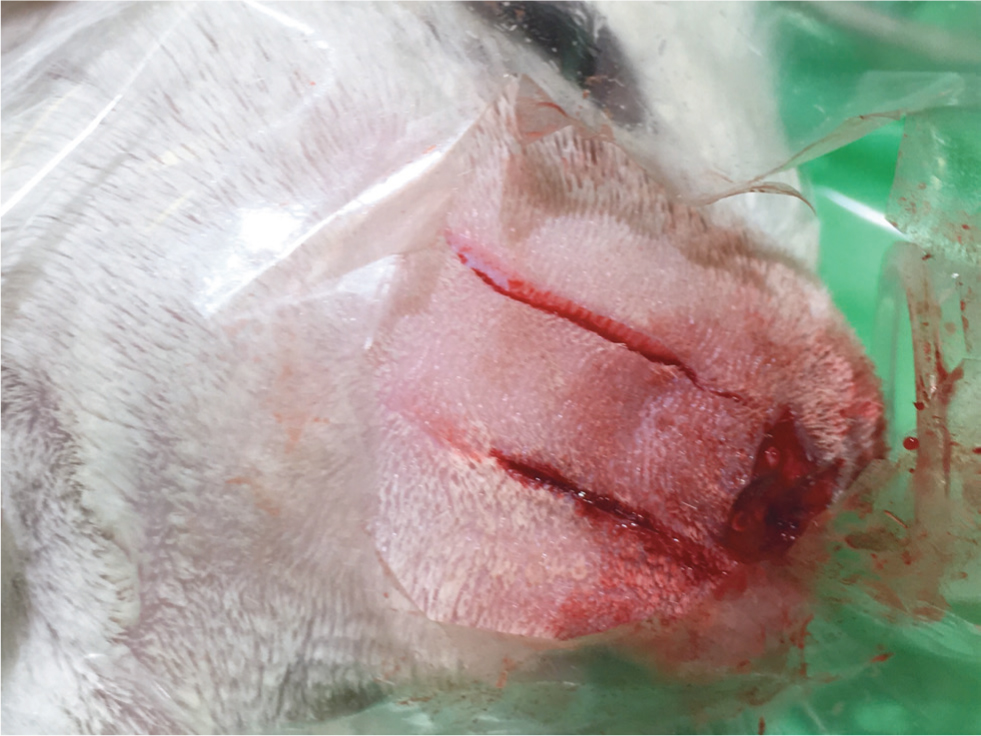

A 2-year-old male guinea pig (Cavia porcellus) was presented with a pea-sized swelling on his right labium, which had appeared a month earlier and had been growing since. Physical examination revealed no other abnormalities. Fine-needle aspiration cytology was performed, which revealed a grade 2 sarcoma with local inflammation. Surgery was scheduled for a week later. After sample collection, the mass grew rapidly (Figure 1).

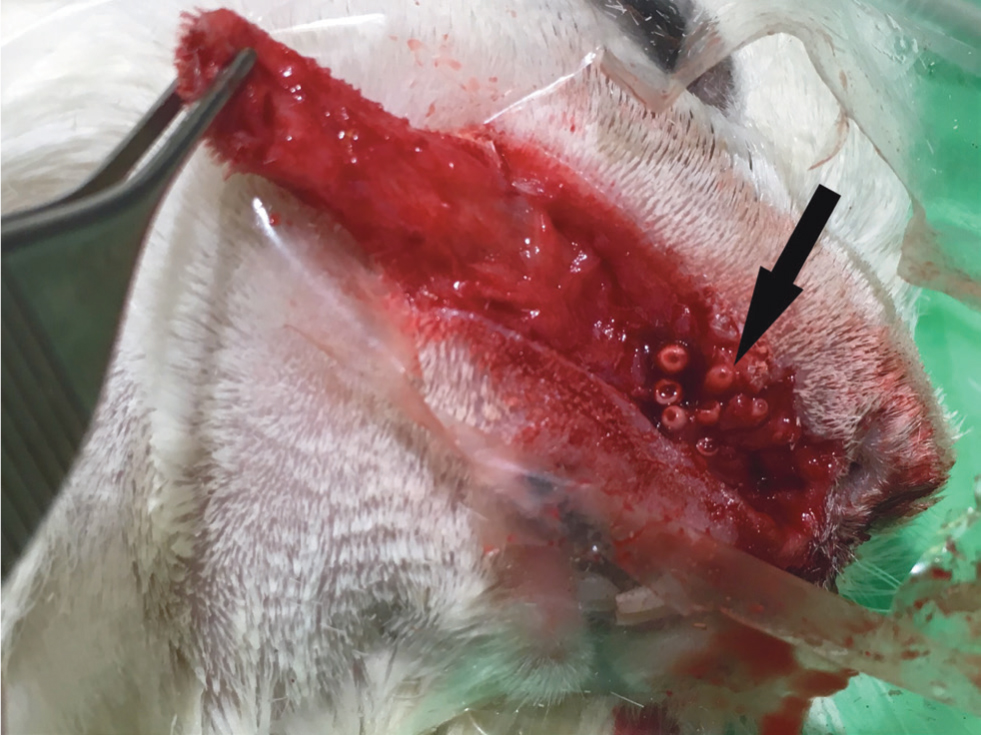

Owing to the unique location of the tumour, the owners and authors opted for removal and reconstructive surgery. The animal was premedicated using 3 mg/kg ketamine (Ketomidor 100 mg/ml, Richter Pharma AG), 0.5 mg/kg midazolam (Dormicum 5 mg/ml, EGIS Gyógyszergyár Zrt) and 0.5 mg/kg butorphanol (Alvegesic 10 mg/ml, ALVETRA u. WERFFT GmbH). The animal was given 15 ml of 0.9% sodium-chloride (Fresenius infusion solution, Fresenius Kabi Deutschland GmbH) and 5 ml of infusion containing amino acids, vitamins and electrolytes (Duphalyte, Pfizer Kft), which were administered subcutaneously. General anaesthesia was induced with 5% v/v isoflurane (Isoflutek, 1000 mg/g, Laboratorois Karizoo), before being maintained with 2.5% v/v isoflurane, using 100% oxygen at 1.5 litres flow via a modified facemask. Radiographic examination with orthogonal projections was performed in order to rule out the possibility of metastasis in the lungs. The animal was then placed in left lateral recumbency on the heated surgical table. The site was clipped, scrubbed with disinfectant liquid (Bradonett, Florin Zrt), treated with disinfectant (Bradoderm Soft, Florin Zrt.) and then isolated using a sterile surgical drape. The eyes were protected with dexpanthenol gel (Corneregel, Bausch and Lomb). The tumour was excised with as large a margin as possible, leaving the nare, the philtrum and the bottom of the lip intact. Any whisker follicles in healthy tissue were preserved whenever possible (Figure 2).

The surgical site was then deepened and the tissue excised, but the mucosa of the mouth was left intact along with any whisker muscles and follicles. Follicles were no longer visible on, or immediately near, the tumour because of the changes to normal tissue structure. Before surgery the amount of skin required for a sliding flap had been calculated. This was essential, so as to cause minimal tension and avoid deformation of the face, while also covering the defect properly. Two parallel skin incisions were made equally to the width of the defect, to prepare the flap (Figure 3). The skin of the flap was carefully undermined to avoid damaging the follicles and the muscles of the whiskers (Figure 4). The flap was advanced to cover the defect on the labium, before being sutured into position using single interrupted 5/0 polidioxanone sutures (PDX, Vetsuture) (Figure 5).

Postoperative treatment included 0.5 mg/kg meloxicam (Meloxidyl suspension, Ceva Santé Animale) and 10 mg/kg enrofloxacin (Enrobioflox 100mg/ml, Vetoquinol), both orally, twice daily until suture removal. In order to prevent gut stasis post-recovery, the guinea pig was syringe fed with guinea pig feed (Trovet guinea pig, Netlaa b.v.), diluted with water. The animal started eating by himself immediately after surgery.

Outcome and follow up

Upon suture removal 10 days after surgery the wound was healing nicely, with just a 0.5 cm wide necrotising area at the very tip of the flap closest to the nose (Figure 6). At 1.5 months post-surgery, only a small scar could be seen under the nostril. The lips were intact, the surgical site was covered with fur and most of the whiskers had grown back (Figure 7). At 4 months post-surgery, no reoccurrence of the tumour could be seen.

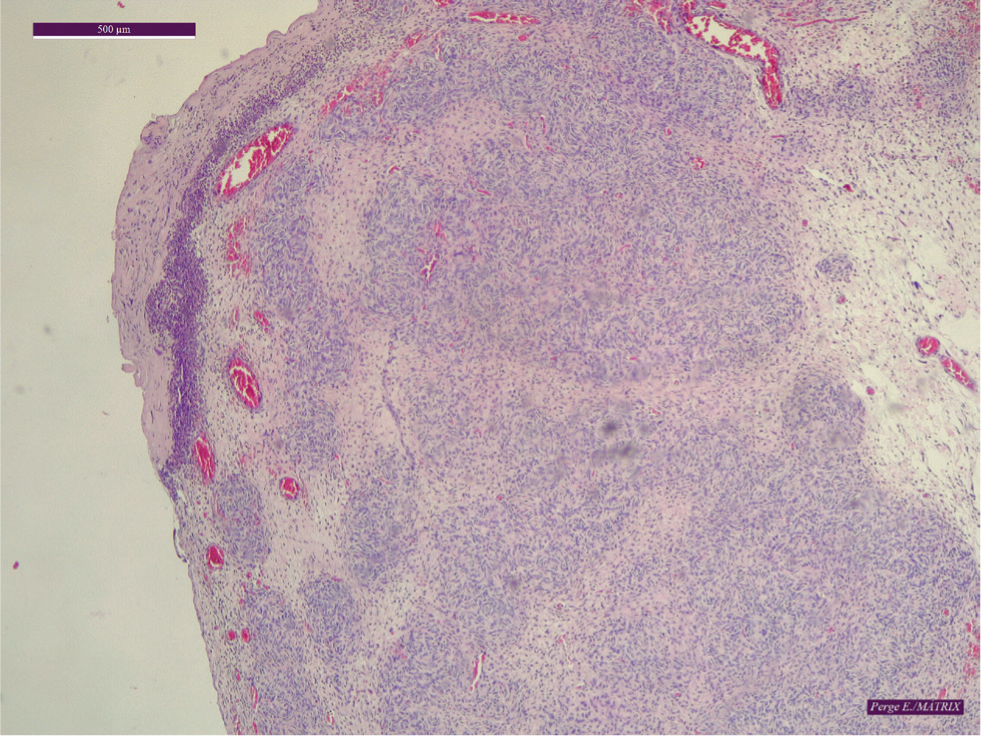

The sample admitted for histopathology showed a diffuse mesenchymal neoplasm partially lifting the epithelial surface, but otherwise situated in the dermis. A large area of the surface of the mass was ulcerated. The nuclei of the tumour cells were large, oval or swollen, spindle-shaped, light-coloured, and heterochromatic, with two-thirds of the cells containing a small prominent nucleolus. The cytoplasm was elongated, fibrous, and more or less vacuolated. The mitotic activity was 6–8 mitoses/10 high-power field. The stroma was diffusely infiltrated by a small number of lymphoid cellular forms and heterophilic granulocytic infiltration was found at the base of the ulcerous surface. Necrosis could not be seen apart from on the ulcerated surface. The histologic margins were reported as incomplete and the mass was identified as a grade 1 soft tissue sarcoma, most likely a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour (Figure 8). It is important to note that the difference in the indication of the fine-needle aspiration cytology (identifying the mass as grade 2), is likely a result of it only withdrawing a small amount of tissue, making it a less precise diagnostic tool compared with histopathology. Furthermore, it is recommended by the authors to always send a sample for histopathologic evaluation after tumour removal, to get a precise diagnosis.

Discussion

Peripheral nerve sheath tumours rarely cause metastasis but can be locally aggressive, with excessive growth rates, as seen in this case. Wide surgical excision is the treatment of choice in cases of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (Baehring et al, 2003). Recurrence is likely if the muscle tissues are infiltrated, so excision with a large and clear margin is advised. The authors performed radiographs before surgery, to rule out metastasis in the lungs. Histopathology was performed to identify the tumour type and to inform future prognosis and monitoring. Histological margins are important, as they show if the excision was complete or if there are any tumour cells left at the surgical site. The surgical margins in this case were not identical to the histological margins, as the tumour could not be removed in one piece. The large section removed first was sent for histopathology, while the smaller tissue pieces removed from the margins of the surgical site were not. Thus, even though histopathology did not show clean margins, the authors believe that in this case the whole tumour was removed, given that the mass was removed in more than one piece. As a result, the guinea pig did not undergo further surgery as suggested by the pathologist and was instead closely monitored for any signs of recurrence. The guinea pig had regular post-surgical check-ups and at the time of writing, 4 months post-surgery, no reoccurrence of the mass could be seen.

Haemangioma removal, in the same region of a guinea pig, has been reported in the past and skin was used from the paranasal region to reconstruct the area. Mentré and Bulliot (2014) found the reconstruction acceptable, as the animal could eat and there was no tension on the lower eyelid, but the lip did not cover the upper incisor. According to the photos, the loose lip typical for guinea pigs, which helps with eating, is missing.

Tension lines in dogs run dorsoventrally on the snout and rostrocaudally on the labia. Thus, closing the wound parallel to these tension lines places less tension on the wound (Stanley, 2012). Based on this, the authors advanced the flap in the rostrocaudal direction, resulting in the lip staying in its anatomical position after the wound had healed.

The guinea pig mystacial pad contains five rows of irregularly positioned whiskers. Individual whisker follicles are large and sensitive in these animals, with sling-like intrinsic muscles connecting the rostral follicles to the caudal follicles in the same row. These muscles can generate fast and large amplitude whisker movements. Social behaviours are important for guinea pigs as they live in groups and whiskers play a role in interactions. The whiskers also protect the eye area, which is important, as guinea pigs are diurnal animals and rely greatly on their vision (Grant et al, 2017). The size of the follicles was helpful during the surgery, as they could be seen and avoided well. The authors very carefully dissected the part of the flap, under which the follicles were found, in order to keep as many of the follicles and muscles intact as possible. No problems in the re-growth of the whiskers, owing to the displacement of the whisker pores with the flap, could be seen. The whiskers penetrated through the skin and the veterinary surgeon did not detect any problems resulting from the flap, such as follicular cysts. Since guinea pigs grasp food using their lips, these are essential for the survival of the animal. During surgery, clinicians put a large emphasis on the lips, making sure to leave a big enough margin for them to remain fully functional.

Guinea pigs have been used in skin flap experimentation (Hirigoyen et al, 1995). Research on flank flaps in guinea pigs has been conducted in the past (Hirigoyen et al, 1995), but no published papers could be found on guinea pig facial reconstructive surgery, apart from the one case study mentioned, so the authors used knowledge from small animal surgery techniques. The authors used the simplest local flap, the single pedicle advancement flap. The width is the same as the width of the defect, but the length has to be longer, since it has to stretch over the defect and cause minimal to no tension in the flap (Pavletic, 2010). The skin on the face of the guinea pig is less mobile than on the rest of the body and a relatively large flap had to be mobilised, compared with the size of the head of the animal. The very end of the flap lying over the defect necrosed, resulting in secondary intension healing along this marginal edge. Necrosis at the end of the flap can be regularly seen in small animal surgery, so the authors were not surprised to see this in the guinea pig as well. The guinea pig used his mouth to eat during the duration of the healing process and as scarring was so minimal, the lips stayed in their anatomical position and the whiskers regrew.

Conclusions

The authors suggest using advancement flaps in facial surgeries in guinea pigs, in a similar way to other small animals, given the very successful outcome of this case. Without the use of a flap, a conventional large wound closure may have caused too much tension, or in this case deformation of the lips and whiskers, which are important for feeding and social behaviour in guinea pigs. Even a relatively large flap can be used on the head of guinea pigs without deforming the skin, but tension lines need to be taken into consideration. The flap used was almost half the length of the head, but it still healed without problems and caused no permanent distress for the animal.